A customer recently commissioned Kevin Courter to paint three cottages on his rural northern California property, then had us frame the three 8 x 10’s. Here it is:

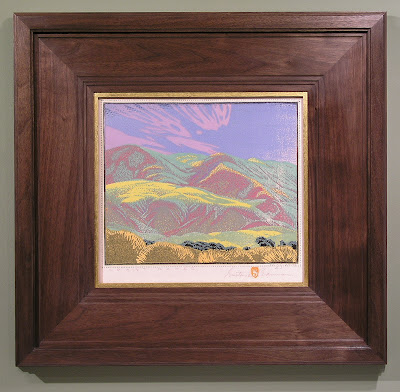

The idea was to create a frame alive to the soft edges as well as architectural subject matter. Given the vernacular cottages, we had to keep it simple but still worthy of the great admiration, felt by both painter and patron, of these charming structures in their locale, and all the wealth of memories and meaning they hold for the family that’s enjoyed them. The over all flat form of the profile was felt suitable to the relatively shallow depth of field and basically flat landscape populated by vertical trees, as well as the strong horizontal composition of the whole piece. It’s a very simple flat with a cap molding, all the profiling done with a 1/8″ radius.

The flat inner, or sight, edge of the frame made sense in terms of the frame construction, lending itself well to the dividers.

Polyptychs are interesting in part because of the trick of creating unity out of distinct parts. Japanese printmakers have done a lot with this idea. As you can see in this example from my portfolio, while the three panels create a whole scene, compositionally each panel also stands on its own.

We chose quartersawn white oak for its wild, rustic quality and stained it Medieval Oak which matches the burnt umber used in the shadows. While the frame thus has an overall shadow quality to spotlight the painting, the wonderful play of sunlight in Kevin’s pictures prompted our choice of a gilt oak slip to surround each panel. So the frame carries out the interplay of light and shadow that makes these images so appealing, but is on balance a shadow presence around the picture.

The metal plate at the bottom of the frame is engraved with the title of the piece, “My Three Sons,” and Kevin’s name.