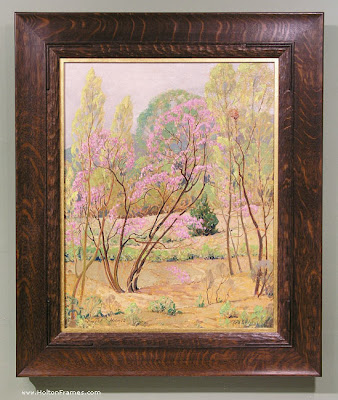

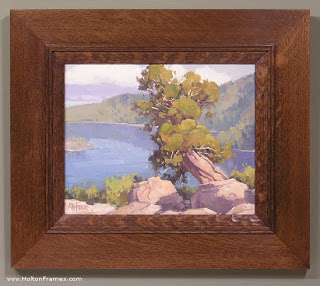

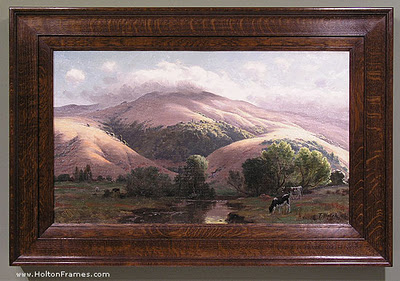

We just framed this 20″ x 16″ canvas by Texan Dwight Clay Holmes (1900-1986) titled “Red Bud”.

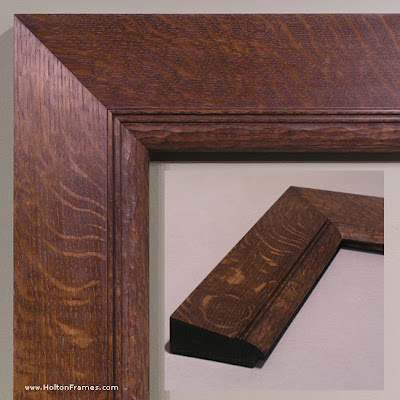

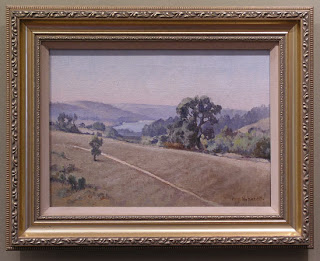

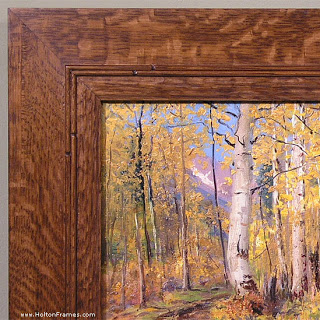

I was especially pleased with the form of the frame profile as an enhancement to both the graceful use of line in the painting (hence the reeding) and the loose brush work (hence the coarse, wild figured quartersawn white oak as well as the carved convex sight edge element). This frame is similar to one on the Charles Partridge Adams, below, which I wrote about here.

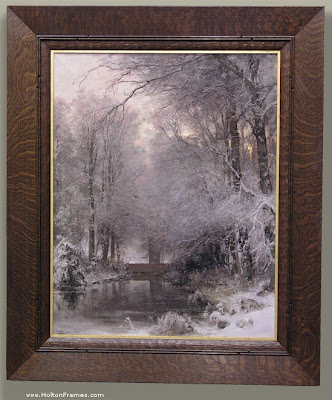

I realize these are pretty similar to the frame on the Louis Apol a couple of entries back. But it’s useful to compare three ostensibly similar frames with nevertheless significant differences when considered with respect to the pictures they’re on.

To make just one point about the frame on the Apol, it’s a slope; you can see the reason behind that choice. Focusing on these two paintings of trees, on the face of it, they’re very similar. Yet the forms of the trees in the Holmes are much finer and more linear and graceful. The most significant difference between these two frames, which are basically flat, is that while the Adams’s frame is perfectly flat outside the reeding and is squared off at the outside, the frame on the Holmes has a subtle cove up toward the outside of the profile terminating in a rounded outside edge. This curl up is basically as subtle as possible while still reading to the viewer. Also, although you can’t see it in the photo, the back is cut in giving this frame a much lighter feel than the blockier one on the Adams. This is a good example of how important it is for the frame design to be alive to the particular characteristics of a painting.

I love how subtle profile forms like this interact with the ray flake in the quartersawn oak. In this case, the rays curve laterally with the subtle cove of the profile (especially on the top), and so echo the curving lines of the trees. Note too the variation on the corner carving, which I focused on in the first entry. Not to put too fine a point on it, but the double reeds on the Adams frame echo the parallel tree trunks throughout the painting, whereas the red bud trunks stray off on their own and so are framed with a single bead, the second bead added to articulate the corners.

Finally, note that these are two bright sunny paintings very suitably served by dark wood frames. A narrow gold liner on the Holmes seems to reflect the sunlight in the painting, which seems very natural (like a window frame viewed from inside a house would reflect the sunny landscape outside). But the entire frame in gold would fail to complement the use of light with its complementary shadow tones.

Most importantly, I think both settings succeed at the great and primary purpose of the picture frame which is to sustain the spirit of the picture into the architectural real.