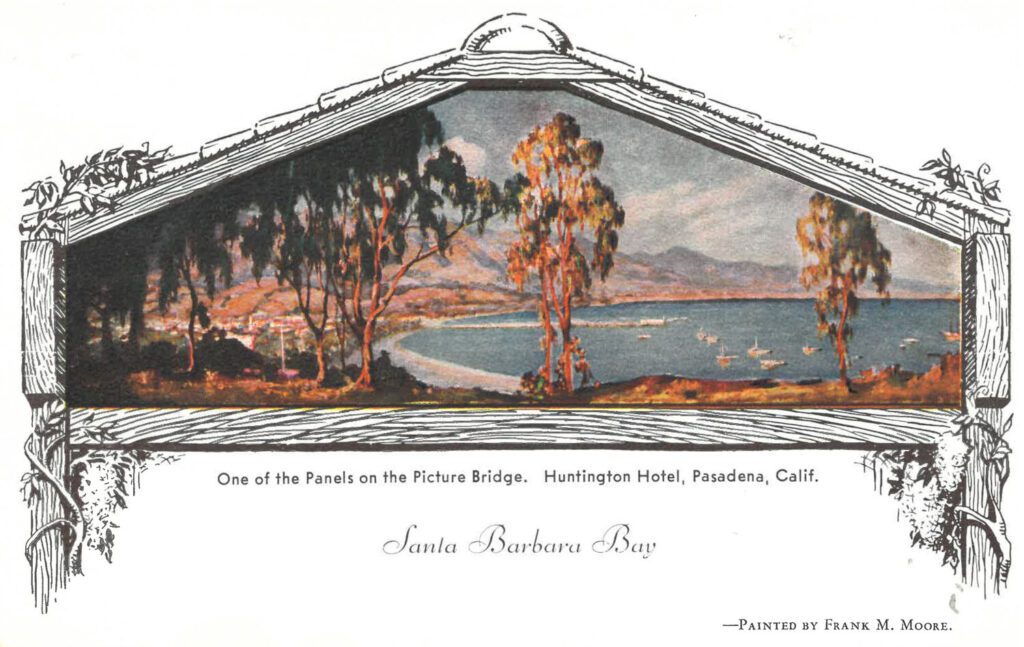

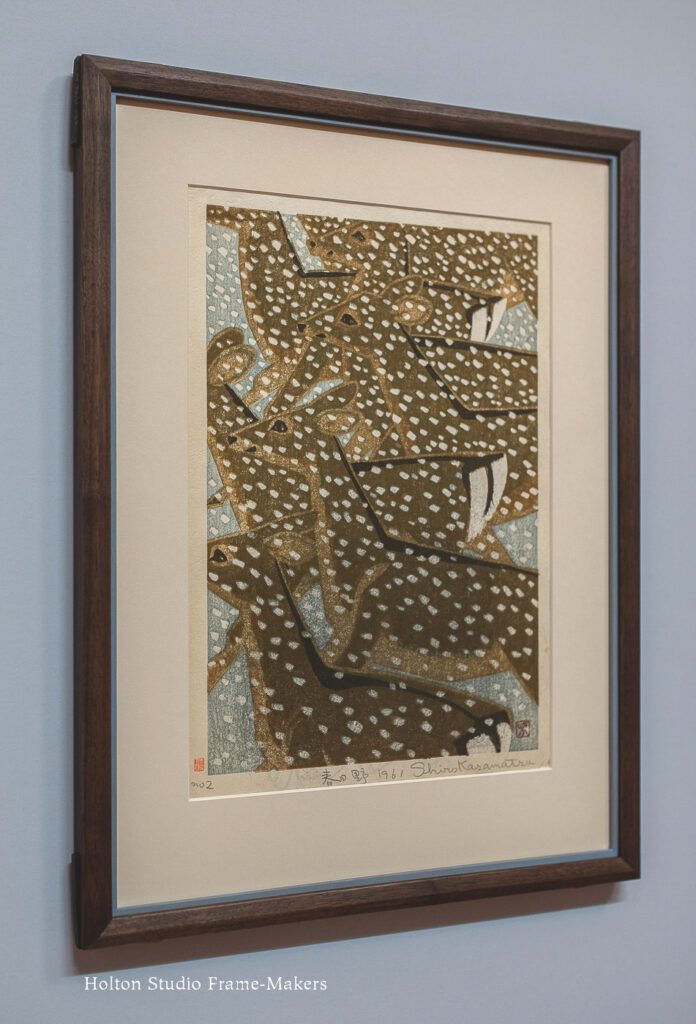

The joy in framing Japanese woodblock prints, one of our specialties, is in exploring the natural harmony that’s possible between the print and the frame. These prints frequently depict traditional Japanese life, including vernacular architectural and craft traditions. Because the art of the frame itself is an architectural craft tradition, these features are a natural basis for harmonious frames.

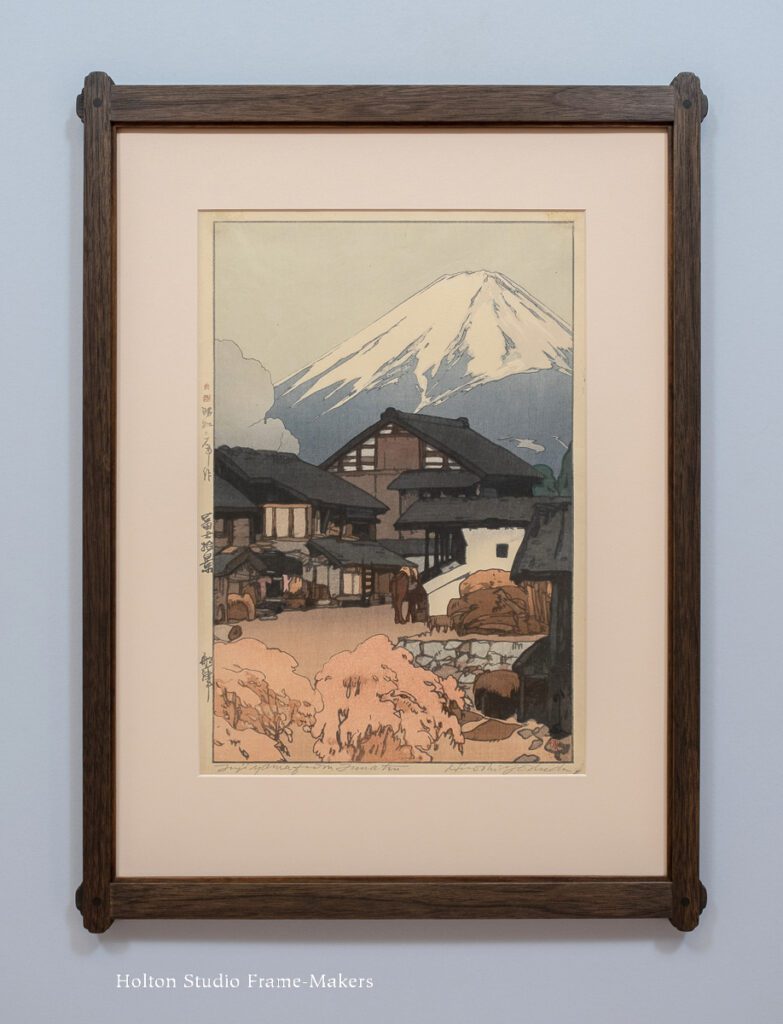

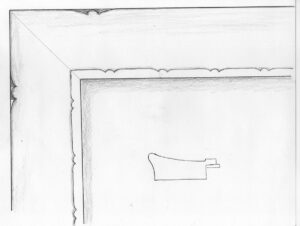

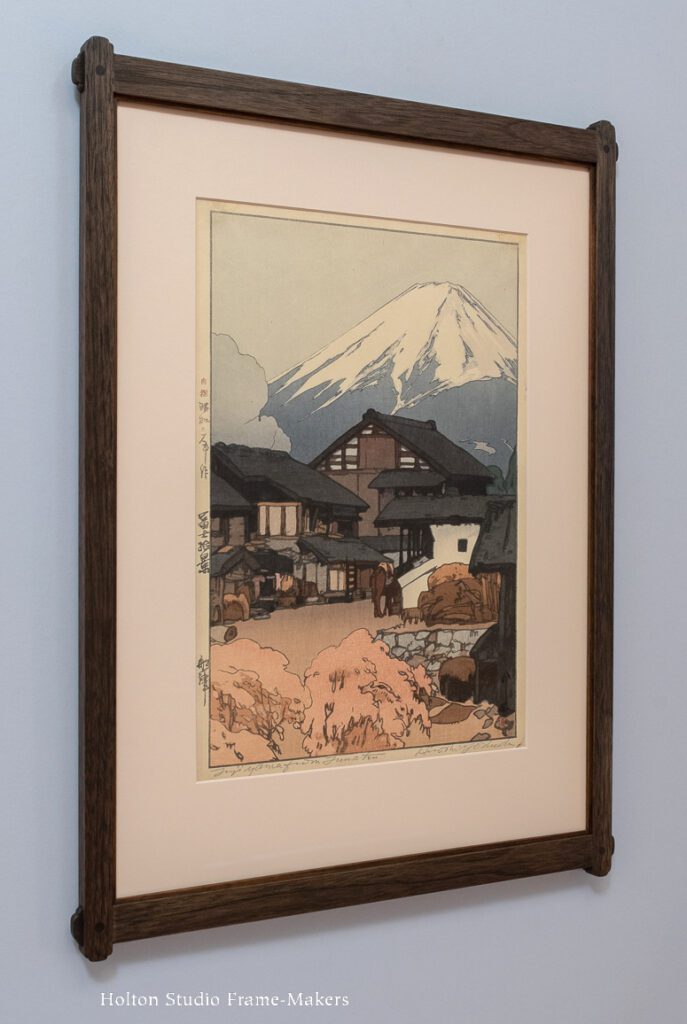

A good example is what I’m sharing today—our framing of a woodblock by shin hanga master Hiroshi Yoshida (1876-1950), one of our favorite Japanese artists (after whom we named the Yoshida frame). This print, titled after the village it depicts, “Funatsu,” is from Yoshida’s series “Ten Views of Mount Fuji.” The image is oban size—about 15″ x 10″—and is dated 1928. The mortise and tenon frame has 3/4″-wide sides and 15/16″-wide top and bottom members.

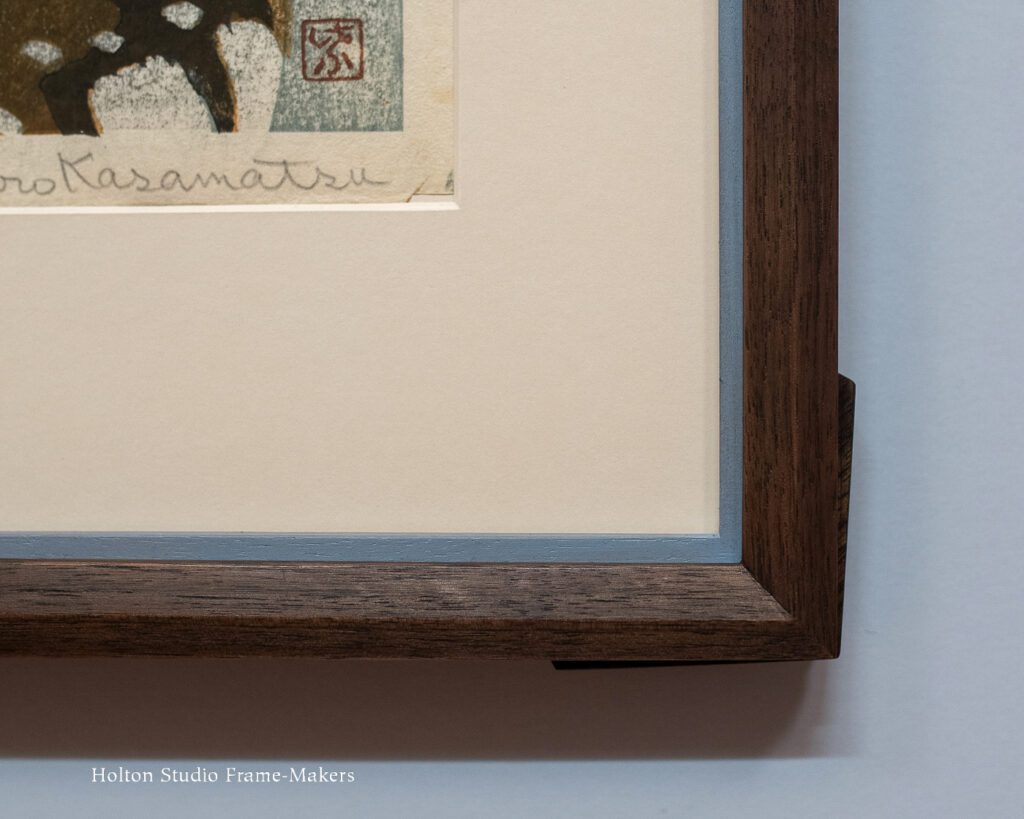

The protruding tenons and horns are shaped to echo the crest of the roof of the building at the center of the print—my response to the traditional village architecture. I also admired the way the structures are defined by a lovely use of subtly complementary cool grey-black and warm brown lines. So I echoed that with similarly contrasting finishes for the walnut frame and the 1/8″-wide walnut slip: linseed oil wax with a black tint for the frame, and a clear oil finish for the slip.

The protruding tenons and horns are shaped to echo the crest of the roof of the building at the center of the print—my response to the traditional village architecture. I also admired the way the structures are defined by a lovely use of subtly complementary cool grey-black and warm brown lines. So I echoed that with similarly contrasting finishes for the walnut frame and the 1/8″-wide walnut slip: linseed oil wax with a black tint for the frame, and a clear oil finish for the slip.

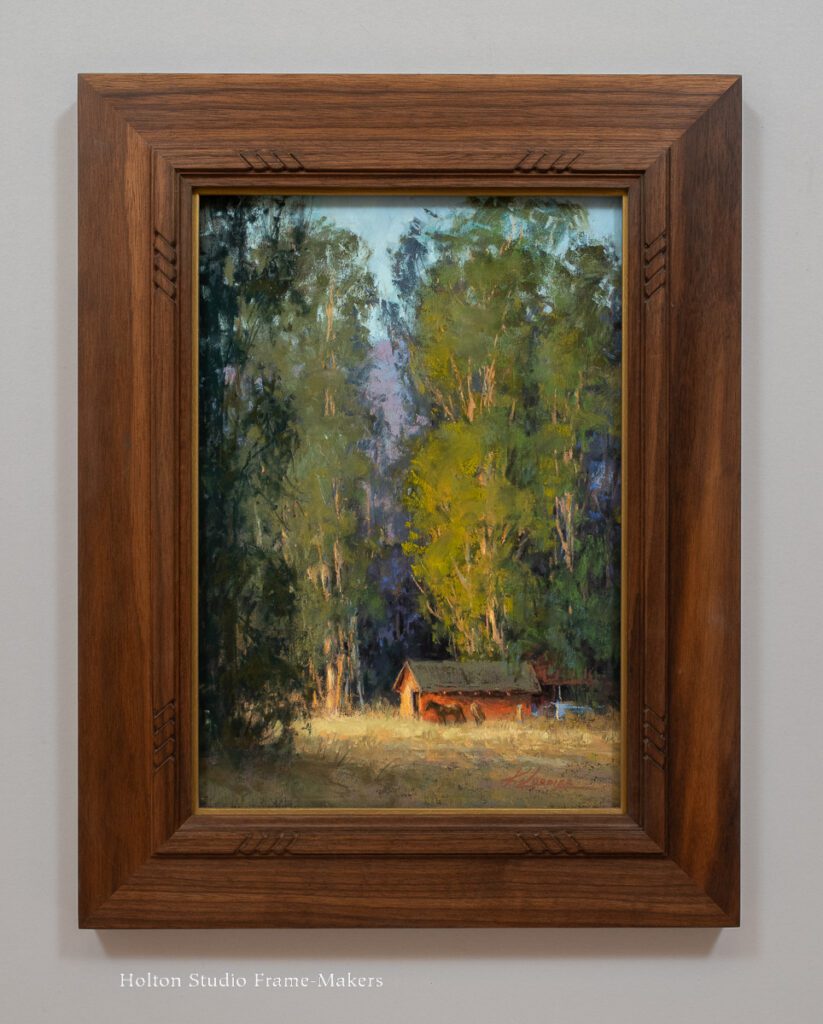

For the same customer, we also framed Hiroshi Yoshida’s “In a Temple Yard”—another shin hanga depiction of traditional Japanese life. Dated 1935, it too is oban size. This frame, which is also walnut with black linseed oil wax, is what we call the Flaired Yoshida. Its lines relate to both the architecture of the bell tower and the form of the cherry tree. Like the “Funatsu” frame, this one has a contrasting slip, but here the slip is painted in the dark blue-green the artist used for the trees and water—an enhancement and complement to the pink of the blossoming cherry tree and orange and red kimonos of the figures.

Both frames were made by Trevor Davis. Craftsmanship means doing things well and with care. The design of such frames, important as it is, only goes so far. Just as the beauty of these prints depends not only on their imagery but to a great degree on the skill and care with which they’re executed, the frame’s beauty depends on sensitive design but, just as much, on the integrity the frame maker brings to the task. As always, Trevor’s frames convey the craftsman’s care and integrity.

Both frames were made by Trevor Davis. Craftsmanship means doing things well and with care. The design of such frames, important as it is, only goes so far. Just as the beauty of these prints depends not only on their imagery but to a great degree on the skill and care with which they’re executed, the frame’s beauty depends on sensitive design but, just as much, on the integrity the frame maker brings to the task. As always, Trevor’s frames convey the craftsman’s care and integrity.

Careful workmanship in the frame is a sign of regard for the print, but especially the element of craftsmanship so crucial to the art of the woodblock print. That shared trait is also another basis for harmony between the two arts.

Both prints are archivally framed with a 4-ply acid-free rag mat, acid-free backing, and Museum Glass.

See more examples of how we frame Japanese prints in the portfolio, here. My post, A Natural Harmony, discusses framing Japanese prints in more detail.

—Tim Holton