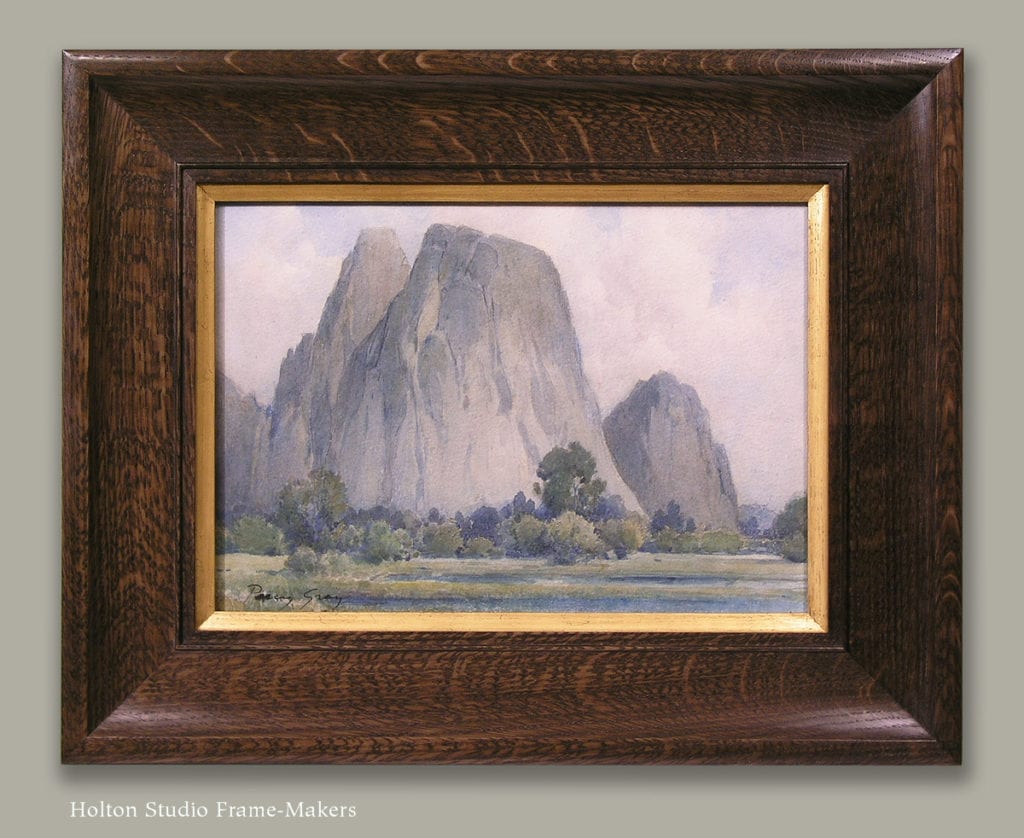

One of my favorite early twentieth century California painters is Percy Gray (1869–1952). We were very lucky recently to have three works by the great watercolorist come in to the shop in quick succession.

The first, which is 16″ x 20″, arrived like this. The frame wasn’t too bad. If you compare the blessedly humble frames like this (which seem to be original to Gray’s work) with the period frames found on paintings by his teachers Virgil Williams and Thomas Hill, it’s evident that frame design had substantially improved after the turn of the century. Just as the Progressive Movement went after the excesses of the Gilded Age, the Arts and Crafts Movement went after the excesses of the gilded edge—overwrought frames used to show off paintings as luxuries and trophies of wealth. Still, the frame felt utilitarian and indifferent to the picture. And as you can see if you click the image to enlarge it, the finish hadn’t worn well (it was metal, not gold, leaf) and the corners weren’t too sound. Probably a low-cost means of getting the painting into a gallery or exhibit, it pulled down the work of an artist at the height of his powers. Also, it lacked the architectural effect on which pictures—especially landscapes—depend for their illusion as “windows,” as well as for their integral role as parts of harmonious rooms. In particular, the gold color of the metal leaf, while in harmony with the painting’s palette, matched and repeated the color of light in the painting rather than the color of the shadows on which the light depends for its effect. In other words, it failed its job of complementing and enhancing Gray’s remarkable handling of the light the way dark wood does.

The first, which is 16″ x 20″, arrived like this. The frame wasn’t too bad. If you compare the blessedly humble frames like this (which seem to be original to Gray’s work) with the period frames found on paintings by his teachers Virgil Williams and Thomas Hill, it’s evident that frame design had substantially improved after the turn of the century. Just as the Progressive Movement went after the excesses of the Gilded Age, the Arts and Crafts Movement went after the excesses of the gilded edge—overwrought frames used to show off paintings as luxuries and trophies of wealth. Still, the frame felt utilitarian and indifferent to the picture. And as you can see if you click the image to enlarge it, the finish hadn’t worn well (it was metal, not gold, leaf) and the corners weren’t too sound. Probably a low-cost means of getting the painting into a gallery or exhibit, it pulled down the work of an artist at the height of his powers. Also, it lacked the architectural effect on which pictures—especially landscapes—depend for their illusion as “windows,” as well as for their integral role as parts of harmonious rooms. In particular, the gold color of the metal leaf, while in harmony with the painting’s palette, matched and repeated the color of light in the painting rather than the color of the shadows on which the light depends for its effect. In other words, it failed its job of complementing and enhancing Gray’s remarkable handling of the light the way dark wood does. Normally, all things being equal, I’d use three different frames on the three pictures. But in this case, the successful frame on the first one became a model for the other two. So, since they’re all in the same frame, here they all are in one post. (Sadly, I didn’t get a picture of the third one in its original framing, which was a white mat and mediocre factory-made gold frame.)

Normally, all things being equal, I’d use three different frames on the three pictures. But in this case, the successful frame on the first one became a model for the other two. So, since they’re all in the same frame, here they all are in one post. (Sadly, I didn’t get a picture of the third one in its original framing, which was a white mat and mediocre factory-made gold frame.)

Our frames, all made by Eric Johnson, are a Compound Mitered profile No. 308 + Cap 811 at 3-1/4″ wide in quartersawn white oak with Dark Medieval Oak stain, with a gilt slip.

This second recent piece we re-framed, shown below (and, at right, as it came to us), Gray probably painted near the town of Monterey and the historic adobe he bought there in 1923. At about 10″ x 14″, it’s smaller than the others, but the customer like the same 3-1/4″ profile on it.

This third recent example (below), like the first, features the eucalyptus trees Gray became known for, inspiring generations of California painters (to the chagrin of the state’s naturalists who despise the non-native eucalypti for their damaging effects on the native habitat).

NOTE, Sept. 18, 2020: This painting is offered by California Historical Design, https://auctions.acstickley.com/lots/view/4-W0WS2/large-percy-gray-watercolor-eucalyptus-path-c1910s.

Opportunities for Harmony

In Plein Air Painters of California: The North, Raymond L. Williams wrote, “The delicately veined limbs and wispy foliage of oaks and eucalypti, often colored in transparent shades of blue and green, were Percy Gray’s signature.” It may be Gray’s love of trees that makes it such a pleasure to provide his work with wooden frames. There’s a natural harmony.

No. 308.2—2-5/8″ Percy Gray watercolor of Mt Tamalpais. Click image to go to Portfolio entry, showing second example as well.

We’ve framed several paintings by this artist in the past—an example is here, at right—and have found that our simple coves with a fine bead or two always work best to sustain and amplify his delicate line work and muted, peaceful atmospheres. In addition to the complementary effect of a dark frame in relation to the captured effects of sunlight that are so crucial to a painting, each frame we’ve used on Gray’s work is wide enough to act as a convincing window frame in the room where we stand, looking through the frame at the scene beyond the plain of the wall. The profile used in every case is primarily a cove, which, leading into the picture, enhances and sustains Gray’s masterful use of perspective to draw us into the scene.

The soft, curved shape also reflects the light in like manner to Gray’s carefully rendered forms defined by subtle tonal gradations of sunlight and shadow. The cove section itself is unembellished, and the whole profile works on the simple principle of complements: the relationship between that broad, plain section and a few finer elements. In the case of the frame profile we used on the recent pieces, there’s a fine bead near the sight edge, and, at the outside, forming the outer cap molding, a wide bead bounded by two filets. The wide bead echoes the larger rounded tree forms (and as a convex form, also complements the profile’s primary concave form); and its fillets, along with the fine bead near the sight edge, pay regard to the painter’s extraordinary line work.

The soft, curved shape also reflects the light in like manner to Gray’s carefully rendered forms defined by subtle tonal gradations of sunlight and shadow. The cove section itself is unembellished, and the whole profile works on the simple principle of complements: the relationship between that broad, plain section and a few finer elements. In the case of the frame profile we used on the recent pieces, there’s a fine bead near the sight edge, and, at the outside, forming the outer cap molding, a wide bead bounded by two filets. The wide bead echoes the larger rounded tree forms (and as a convex form, also complements the profile’s primary concave form); and its fillets, along with the fine bead near the sight edge, pay regard to the painter’s extraordinary line work.

We used an even simpler profile designed on the same principles for the previously framed painting of Mt. Tamalpais, shown above. In that case, the simpler shape, without the cap molding, was used to repeat the features of the landscape—the sweep of the hillside in the foreground as well as the silhouette of the distant mountain. Another simple cove profile, working on the same complementary principles, is shown on the painting of Yosemite, right.

While we can be impressed with Gray’s technical proficiency, if we focus on that, we miss the purpose of that proficiency which was the attitude of deep devotion and care that inspired the artist to refine his technique. Through such refinement, Gray was able to capture the complexity, nuance, and intricacy of the natural world of California. Above all, the beauty of Gray’s work stems from his humility in the face of California’s awe-inspiring landscape, and his insistence on subordinating his own work to nature’s. His remarkable skill demonstrates above all a commitment to an understanding that the most fundamental duty of the painter is to help people see nature’s beauty.

In keeping with that—in harmony with it—the beauty of the frame lies in three things: service to the picture and its objectives, nature’s materials, and careful workmanship. Regarding the first, the frame’s duty is to serve the artist’s purpose of helping people to see nature’s creation. Gray’s characteristically humble approach to painting is served well by frames that aim simply to serve the picture and honor the beauty of nature. That beauty is present—and this is the second thing—in not only the picture but the material of the frame, wood. The relatively plain profile is a counterpoint and complement to the wild figure—the “ray flake”—of quartersawn white oak. And thirdly, the success of the frame depends on its workmanship, which is, for the frame-maker as it was for artists like Percy Gray, not something arbitrary and merely technical, but a direct expression of care (and the theme of yesterday’s Labor Day post, that “work is love made visible”).

These sorts of concerns, as Gray understood them in relation to painting, represented a kind of “sanity” that he would feel compelled to defend in the face of forces of “insanity” that would consume the arts in coming decades.

Percy Gray

Percy Gray

Henry Percy Gray’s biography suggests that he was single-minded in his life’s work as a pictorial artist. Gray was born into a family of artists in San Francisco in 1869, and enrolled in the California School of Design at age seventeen, studying with the school’s director Emil Carlson, as well as (as noted) Virgil Williams, and Thomas Hill. Later he would move to New York to work for the New York Journal, taking the opportunity to study with William Merritt Chase at the Art Students League, before being dispatched by the newspaper back to San Francisco to cover The City’s recovery from the 1906 Earthquake. He decided to stay, initially settling in Alameda and painting the island town as well as other East Bay sites, including Berkeley; but over his lifetime moved about the region seeking, one suspects, new scenery to paint.

Gray’s meticulous care served him well in his difficult quest to earn a living in commercial illustration, as he could apply his fine rendering skill to etching, photogravure, and the methods of photomechanical reproduction used by magazines and newspapers.

But fundamentally that capacity for careful detail was an honest, devotional expression of his deep love for his native land.

Accustomed as we are today to regarding California as at the leading edge of a rapidly changing world, I’m not sure we fully appreciate how removed from the maelstrom of industrialization California still was in the first decades of the century. At the same time, the state’s artists were acutely self-conscious about their role in shaping California’s place in history and the opportunity Californians had for redeeming a civilization that had become debased from nature. It was a view dating back at least as far as our city’s namesake George Berkeley’s early 18th century predictions that “the muse” would seek a world “Not such as Europe breeds in her decay,” but “happy climes” of “genial sun and virgin earth” where “The force of art by nature seems outdone,/And fancied beauties by the true.” In Gray’s own time, Arthur and Lucia Mathews sustained Berkeley’s hopes in allegorical depictions such as “California” that saw a new civilization tamed by nature and a renaissance of the ancient arts, working together in their full variety and scope.

A Bid for Sanity In a Transformational Age

But such hopes failed to account for the explosive forces of industry and commerce in the nineteenth century, which would eventually overtake the lives of the state’s nineteenth century immigrants—just as it had, in immeasurably more brutal ways, those of native Californians beginning a couple of centuries before. In his later years, Percy Gray helped found the San Francisco chapter of the Society for Sanity In the Arts which protested the rise of modernism after the Great War. The society’s chief founder, Chicagoan Josephine Hancock Logan, in her 1937 book, Sanity In Art described the landscape of the art world that so dismayed her—a description in which we can readily recognize the plight of an artist like Gray who’d spent a lifetime honing his skill:

Soon newspapers were filled with stories of untrained aspirants who had just been discovered to be great geniuses. The work of children was highly extolled and a new school of art instruction came into being wherein the youngster was supplied with the material and left to himself, the teacher being careful not to intrude on budding genius with the blight of such superior knowledge as he, or she, might have. With all this in the air, it was not difficult for the art student to impress a jury of modernistic temper. It was however very difficult for the man or woman who had acquired that ready, deft, facile manner of limning things which marks the professional. “The old ones would like to, but they can’t do this modern stuff,” was the gleeful cry of the wreckers of the art world. And they were right, because the true artist could not use his brushes to falsify his talent, since it would be impossible for him to attempt the new trend without giving it too much grace and balance. So the beginner crashed the barrier and felt he had arrived. He went no further; there was no further to go in this direction, and soon other beginners stormed in.

A conservative, perhaps even reactionary, response to such unsettling trends was certainly understandable. The world that had educated and shaped the values of artists like Percy Gray—a world in which nature still reigned; a world in which devotion to one’s art, one’s trade, was still assumed to be honored, respected and rewarded—had been leveled by the most revolutionary transformation in history. If the Society for Sanity In Art’s categorical rejection of the modernists betrayed a narrow-mindedness and stubborn refusal to see such current realities as the modernists were confronting, we can at least acknowledge the virtue of denouncing the modernists’ complicity with the age of money and machines in degrading, devaluing and destroying two things the arts had always treasured most highly: nature and manual skills. Living today with the consequences of our destruction of those life-generative powers, “insanity” does not seem like too harsh a word.

As in all transformational times, a great re-framing was underway—inevitably in picture frames, but more significantly and largely in a new zeitgeist, a new ethos. The world was governed by pursuit of the novel; by the ephemeral, private life of the psyche; by the short-lived relevance of experimentation. A world framed by trees and led by the pace of nature was transformed into one relentlessly man-made, framed by urban and industrial architecture and constant, head-spinning change. Fittingly, in his later years, after his wife died, Gray moved one last time, from a life among the oaks, bays and eucalypti of still-rural Marin County, to a life amidst the steel, concrete, and glass of booming San Francisco. There, he rented a room at the Bohemian Club and took a studio, alongside some of The City’s most illustrious artists and writers, in the famed Montgomery Block, where, in 1952, Percy Gray died at his easel, persevering in his belief that what is timeless and true will once again find real and substantial, enduring place in the world.

Finally, another Gray from several years ago, shown before-and-after re-framing. (The frame is the same No. 308.2 used on the painting of Mt. Tamalpais, above.) This is one on our page, “Fixing ‘a Very Prevalent Error’: The Cabinetmaker’s Answer to the Gold Frame Convention.”

See a beautiful later Percy Gray, apparently in its original frame, appraised by Aaron Bastion of Bonhams, on Antiques Roadshow—

« Back to Blog