Just finished framing this spectacular 1875 Alpine landscape oil painting by British artist Benjamin Williams Leader (1831 – 1923), titled “The Wetterhorn from Rosenlaui.” At 72″ x 60″ it has a powerful presence (see last photo for scale). Commissioned by a Member of Parliament, John Derby Allcroft, the year it was painted it was displayed at the Royal Academy, where Leader’s work was shown in every summer exhibition from 1854 through 1922.

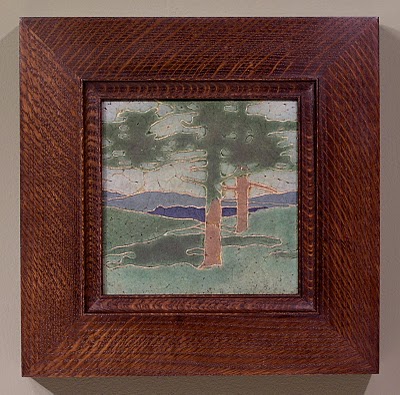

We made a 6″ wide stained quartersawn white oak compound frame with a chamfered mortise-and-tenon flat and gilt oak liner. The chamfer has carved points that articulate the corners with a detail that also picks up a form pervasive in the painting.

|

| Corner detail |

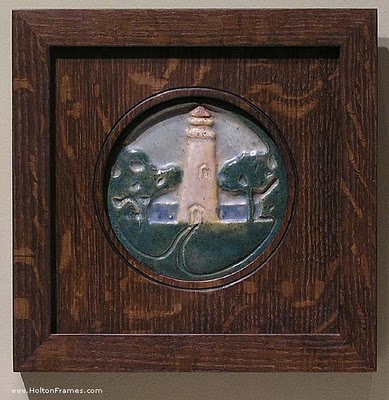

Below is the painting in its old Victorian makeshift frame—a conventional 19th century exhibition frame heavy on compo (molded plaster-like material meant to pass itself off as carving).

Clearly influenced by John Ruskin’s pleas to painters to go to nature, to see her both truly and reverently—and sharing with Ruskin a passion for the Swiss Alps—Leader contributed in his way to the great project of re-framing art, led by Ruskin and the Pre-Raphaelites. I wonder if, while breaking with convention on the canvas itself, he followed the Pre-Raphaelites, Whistler and others to make his ideals real in the form of the picture frame itself. If so, I hope our efforts would have met with his approval.

This is the third Leader we’ve had the privilege of framing. Another is on my site, here.

View this Leader in the Portfolio…

|

| The painting with Eric Johnson next to it to give a sense of scale (Eric’s over 6′ tall). |