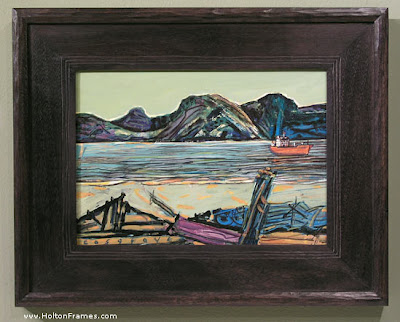

A customer recently brought in this little (5-3/4″ x 8″) oil on board by Glasgow painter James Cosgrove(b. 1939). The stained walnut frame was designed entirely to the painting, with a carved cushion rim around a flat with fine carved flutes. I’m very pleased with the harmony of line and form, as well as color—a rare occasion when black works best with a painting.

Archives

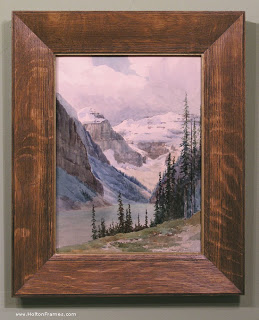

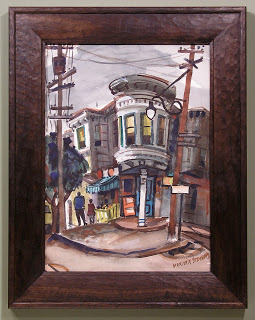

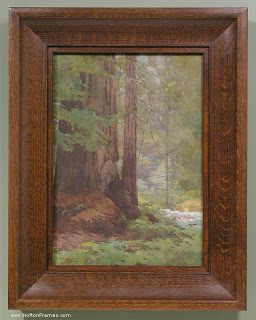

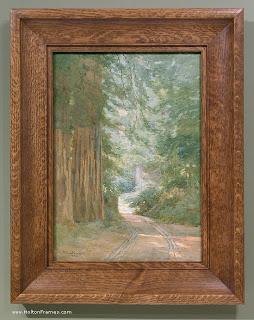

Framing Historic California Watercolors

We’ve recently had the pleasure of framing several watercolors by notable California artists working in the early twentieth century.

Maynard Dixon (1875-1946):

Chris Jorgensen (1838-1876):

William S. Rice (1873-1963):

Marjorie Stevens (1902-1992; available through North Point Gallery):

Lorenzo Latimer (1857-1941; these available through North Point Gallery):

Davis Schwartz (1879-1969):

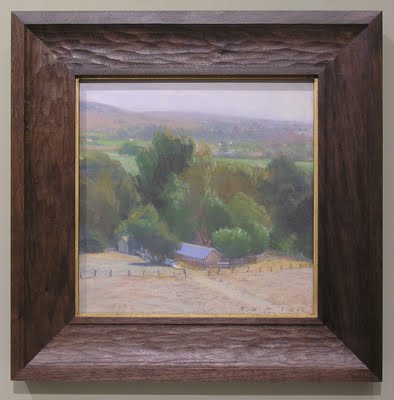

Recent Bill Cone work, and framing

Bill Cone recently brought in these two beautiful pastels for The Summer Show.

|

| “Gateway Morning,” pastel on paper. 8″ x 8″. |

|

|||||||||

| “Wildflowers,” pastel on paper. 9″ x 12″. |

We’ve also just completed framing a few of Bill’s works for a customer. Here they are:

All are profiles that are simple but designed to suit Bill’s direct and no nonsense views of the natural landscape. They’re done in carved walnut, muted with a light stain, which is just right with the artist’s palette and texture.

Bill’s blog is always fascinating. Top notch!

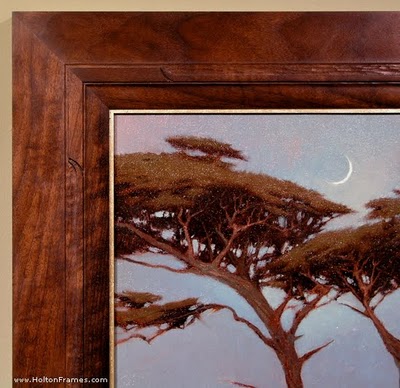

Framing Kevin Courter’s “Cradled Moon”

Enjoyed framing this 12″ x 14″ oil for Kevin Courter, now at New Masters Gallery in Carmel. Chose walnut for its color (used a light stain to get the harmony just right) and because it’s good for carving. Chose a flat profile, since it’s a flat composition, but at the sight edge it’s got a very subtle convex, or ovolo, form echoing the form of the treetops cradling the moon. The frame similarly cradles the painting. The carved pattern takes its cue from the crescent moon and the branches. The narrow slip with lemon gold leaf matches the moon.

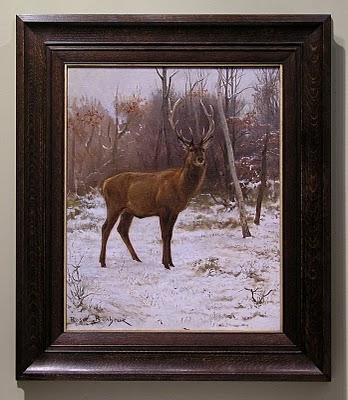

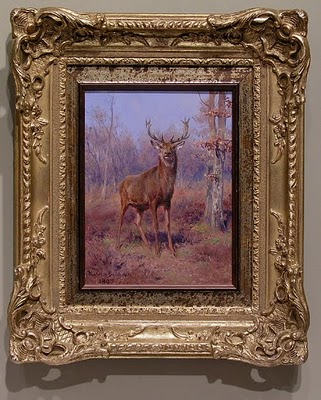

From Gold to Oak—I: Re-Framing Rosa Bonheur Stags

The theme of this post, replacing gilt frames with dark wood frames, has since been greatly expanded upon on a page created a couple years later, “Fixing ‘A Very Prevalent Error: The Cabinetmaker’s Answer to the Gold Frame Convention,” here.

Have you ever looked at a painting and realized that you were fighting to see past the frame, that the frame was actually inhibiting you from seeing the painting? Maybe you’ve held your hands up to one eye and used them to block out the frame. That was very much my reaction—and I suspect the reaction of the customer who brought it to me—when I first laid eyes on this sweet little oil by the great French painter Rosa Bonheur. The elaborate, swirly gold frame was so imperious, showy and unsympathetic to everything about the picture—the subject, palette, line work, forms and, above all, the rustic spirit—that it actually felt laborious to really study and appreciate the painting itself. (The owner was also seeking a frame that would be more suitable to the painting’s destination in a log home.) At just a little over 8″ x 6″, it was being eaten alive by some past owner’s or dealer’s insecurities (it didn’t help that a makeshift gold colored liner had been used to make the painting fit a 10″ x 8″ frame). The poor creature appears inexplicably displaced to some Parisian bank manager’s parlor, and seems to stare at us as if to say, “What the heck am I doing here?”

Have you ever looked at a painting and realized that you were fighting to see past the frame, that the frame was actually inhibiting you from seeing the painting? Maybe you’ve held your hands up to one eye and used them to block out the frame. That was very much my reaction—and I suspect the reaction of the customer who brought it to me—when I first laid eyes on this sweet little oil by the great French painter Rosa Bonheur. The elaborate, swirly gold frame was so imperious, showy and unsympathetic to everything about the picture—the subject, palette, line work, forms and, above all, the rustic spirit—that it actually felt laborious to really study and appreciate the painting itself. (The owner was also seeking a frame that would be more suitable to the painting’s destination in a log home.) At just a little over 8″ x 6″, it was being eaten alive by some past owner’s or dealer’s insecurities (it didn’t help that a makeshift gold colored liner had been used to make the painting fit a 10″ x 8″ frame). The poor creature appears inexplicably displaced to some Parisian bank manager’s parlor, and seems to stare at us as if to say, “What the heck am I doing here?”

Relief finally came when I removed the work from its setting and could enjoy this stately fellow whom Mademoiselle Bonheur had distinguished so skillfully. Seeing past the significance of the painting and refusing to be awed by the signature in order to appreciate the work itself, I could craft no better solution than this plain and simple 2-5/8″ wide flattened scoop with a single bead at the sight edge. At last, we can see the painting without effort, and the stag is in his natural habitat, warily watching us as intruders of his home.

Relief finally came when I removed the work from its setting and could enjoy this stately fellow whom Mademoiselle Bonheur had distinguished so skillfully. Seeing past the significance of the painting and refusing to be awed by the signature in order to appreciate the work itself, I could craft no better solution than this plain and simple 2-5/8″ wide flattened scoop with a single bead at the sight edge. At last, we can see the painting without effort, and the stag is in his natural habitat, warily watching us as intruders of his home.

A larger Bonheur of similar subject matter came in about a year later, with a similarly overbearing frame. Damaged in transit, the composition—or “compo”—breaking off demonstrates the dubious

service of frames like this as protectors of paintings, not to mention the debased character of compo as fake carving. At 22″ x 18″, this canvas called for a larger and stronger frame, although with the same approach to line and form which we’d taken with framing the earlier painting.

The suitably rustic spirit of the quartersawn white oak frame molded to harmonize in line and form with this quiet but accomplished work, a dark stain to lead the eye to the lighter painting (the eye goes to light; frames are generally more successful when they’re darker than the picture), and a touch of pale gold leaf on oak at the sight edge to echo the painting’s contrasts and lend a note of honor to this noble beast all contribute to a setting that sustains and expands the spirit of this fine work and allows us at last to see and admire the painting.

Framing Paintings—I: Kevin Courter’s “Colusa Sunset”

“All true art is praise,” as John Ruskin said, getting right at the heart of picture-making (and blowing the top off a lot of pretentious blather about art, too). Last fall Kevin Courter brought in this work of praise, a 16″ x 20″ oil on linen, less than 2 weeks before our show, “A Heaven in the Eye” was to open. It’s a stunner, as you can see, and to a frame-maker an inspiration. My enthusiasm and the extra focus imposed by the deadline spurred me to produce one of my favorite recent pieces.

Kevin says this is near Gray Lodge Wildlife Area off I-5 in Colusa County — a place I haven’t been to but which a number of customers praised to the skies (how else to say it?) for the astonishingly huge flocks of geese and rare species to be seen there. It’s a place where you can feel as though bird life is as strong as ever; as if life everlasting still means something (as it surely does, after all); as if we can still witness nature’s eternal beauty (which we can). It’s some place to praise.

Most of the framing we do is more restrained, simple, frank. But one thing a frame legitimately does is sustain and amplify the praise the picture has started, and this praise can be as lavish as you like, so long as the frame remains subordinate to the picture and obeys the first law of the universe: the law of help. Or, to borrow William Morris’s words, “all this is not luxury, if it be done for beauty’s sake, and not for show.”

There’s a very important distinction between this use of decorative treatment to enhance a painting and the illegitimate praise the frame has frequently been enlisted to lavish on, not the subject of the picture but the picture itself—the picture as trophy, as symbol of status and wealth. In this role the frame is often oddly blind to the character of the picture. Is a slick gold frame ever well-suited to a painting of a cow or a weather-beaten barn—or a muddy river bank? That’s the frame as unflattering flatterer and sycophant, not as friendly home or accompanist.

The frame’s praise of nature begins with suitable materials, and this was a beautiful piece of American Black walnut, with rich native color (a little stain was used to get the color harmony just right) and a bit of interest in the grain but still even and workable for carving. I chose walnut for the cool brown native color and the tight grain which is better for detailed carving. Also, our most frequently used wood, quartersawn oak, has strong figure that can compete with this more refined kind of carving.

It’s hard to take frame designs to this level on smaller or more impressionistic or on tonally subdued paintings. But a work as strong as this one leaves room for the frame-maker to be more free. This piece was large enough, had enough tonal power, and was simply so reverential in spirit that it called for a more elaborate frame. It is also detailed and highly rendered enough to suggest more detail in the frame.

The key to having a frame be more elaborate without upstaging the painting is the harmony of the elements (line, form, material, color, texture) and economy in their use: every element and detail should have a reason for being—should be justified by the painting, and echo an element or detail in the painting. In other words, key to keeping the frame subordinate to the painting is having nothing in the frame that isn’t a complement to, or echo of, something in picture. In this case, the primary form in the painting is the cloud. This frame’s response to that form is obvious (the carved bead with rounded stops at the corners, the scallop stops on the flat). The amount and strength of line in the frame must be economical as well—constrained by what suits the painting. I had fun picking up the fine grasses in the foreground with fine carved lines at the frame’s sight edge.

I don’t expect to ever make another frame exactly like this, because there’ll never be another painting exactly like this. That’s one of the tests of a truly living art form: it’s alive to the other arts—and to the world—-in specific ways. But it’s not hard to do. It just requires taking the time to truly see and appreciate the adjacent arts. And it demands that we work with both freedom and humility in our service to the other arts.

It helps, too, to have inspiration, which in this case was provided by Kevin Courter and the landscape of Colusa County, California.

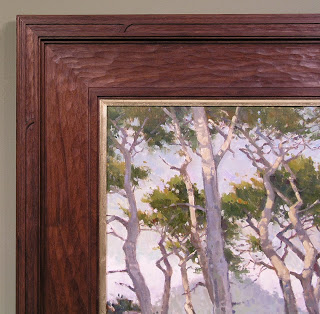

Carved Walnut

Of all the woods we use, we tend to emphasize quartersawn white oak. But walnut has always been a big favorite too, especially for carving. In preparing for the Paul Kratter show in June, the painting we decided to use for the publicity suggested walnut. Here’s a corner detail of the frame, which is a compound design, meaning it’s composed of more than one molding. This one has a cap molding as well as a liner. The liner has pale gold leaf laid directly on the walnut so the grain comes through.

Of all the woods we use, we tend to emphasize quartersawn white oak. But walnut has always been a big favorite too, especially for carving. In preparing for the Paul Kratter show in June, the painting we decided to use for the publicity suggested walnut. Here’s a corner detail of the frame, which is a compound design, meaning it’s composed of more than one molding. This one has a cap molding as well as a liner. The liner has pale gold leaf laid directly on the walnut so the grain comes through.

The color of walnut harmonizes well with many pieces because it’s rich without being too intense. We typically stain it – this one has a light stain – to mute it even further.

We use walnut frequently for drawing frames (i.e., narrow profiles), but it’s often great on paintings and other items.