|

|

| Before |

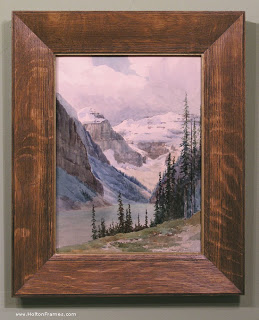

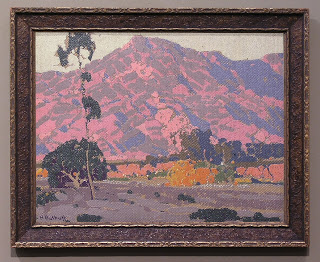

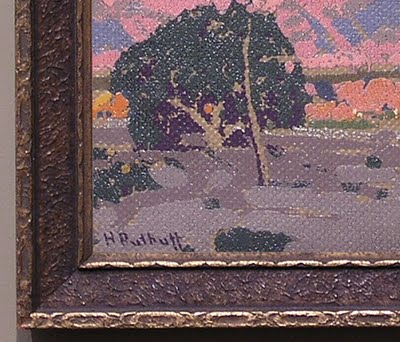

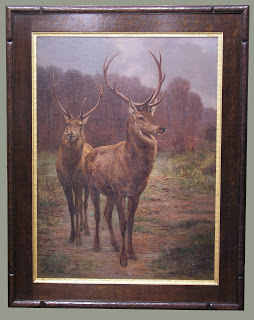

The “before” shot demonstrates the typical conventional contemporary framing approach for this type of piece. The silk mat and curly-cue gold frame seem intended for nothing but projecting an air of sophistication around the painting. The glaring white mat contrasts so much with the deep shadowy tones of the painting that it actually interferes with the eye’s ability to adjust to the light the artist captures so effectively. In so doing, it spoils the painting. The incongruous framing not only fails to serve the painting itself, but creates a harsh divide between the painting and its surroundings. The gold frame may not look too bad in the photo above, but is a production compo molding nailed together. One corner was already broken. The frame didn’t hold up to scrutiny — or to life (see detail below)!

|

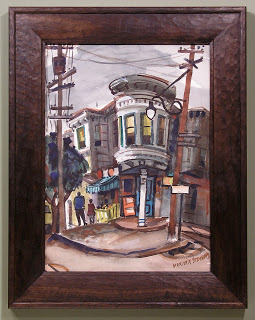

| Corner of old frame |

What the painting needed instead was a dark frame, quiet and soft in profile, with just a halo of gold to highlight it on the wall while continuing and sustaining the spirit of the picture into the architectural realm.

|

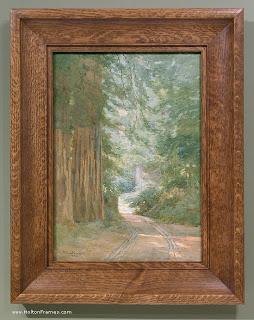

| After |

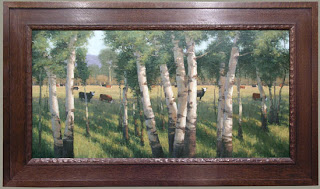

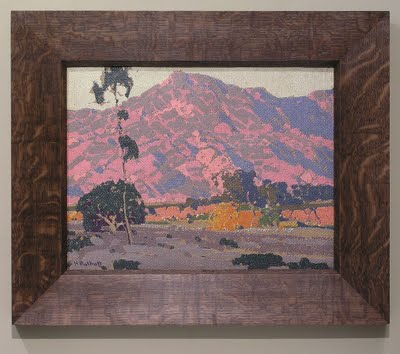

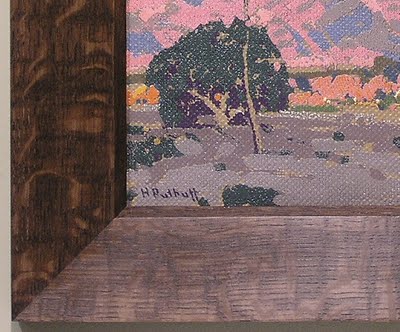

Titled “Under the Oaks,” the painting’s rustic spirit — completely ignored by the previous framing — and of course the oak trees Yard painted called unquestionably for an oak frame. (The protective aspect of the oak frame is another level of meaning for a depiction of oak trees sheltering a shepherd.) This is a simple 2-3/4″ wide scoop in our Century Series (No. 308.2) around a 3/4″ ogee liner oil gilded with 23 kt leaf. We stained the scoop a burnt umber (our Medieval Oak stain) matching the shadows — the frame being a shadow effect around the painting, to draw your eye to the lighter painting. Two fine reeds at the sight edge of the dark molding echo some of the fine details in the painting. A closer view of the frame:

|

| No. 308.2 (“Michigan”) — 2-3/4″ with 3/4″ gilt oak ogee liner |

Taking the time to craft the frame well with splined closed corners (finished after joining) and attention to finishing off every detail actually has an aesthetic effect, a sense of caring made tangible, not conveyed by digital photos.

The piece is framed archivally by using a hidden, or “gasket,” mat under the liner. It’s purpose is to separate the picture from the glazing (in this case u.v.-filtering acrylic). The rabbet is lined with a metal tape to isolate the acids in the wood from the watercolor paper.

Thank you to Montgomery Gallery, where this beautiful painting is available.