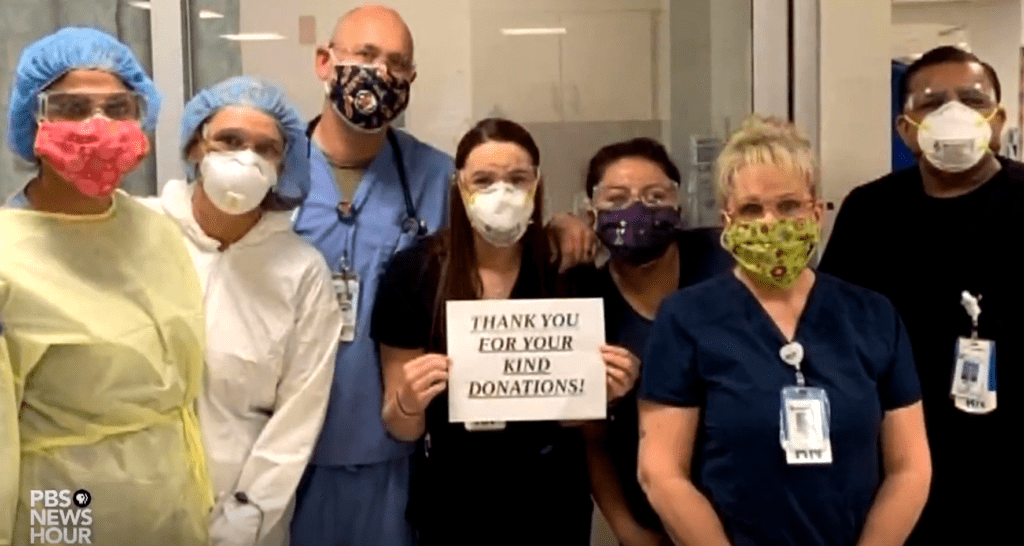

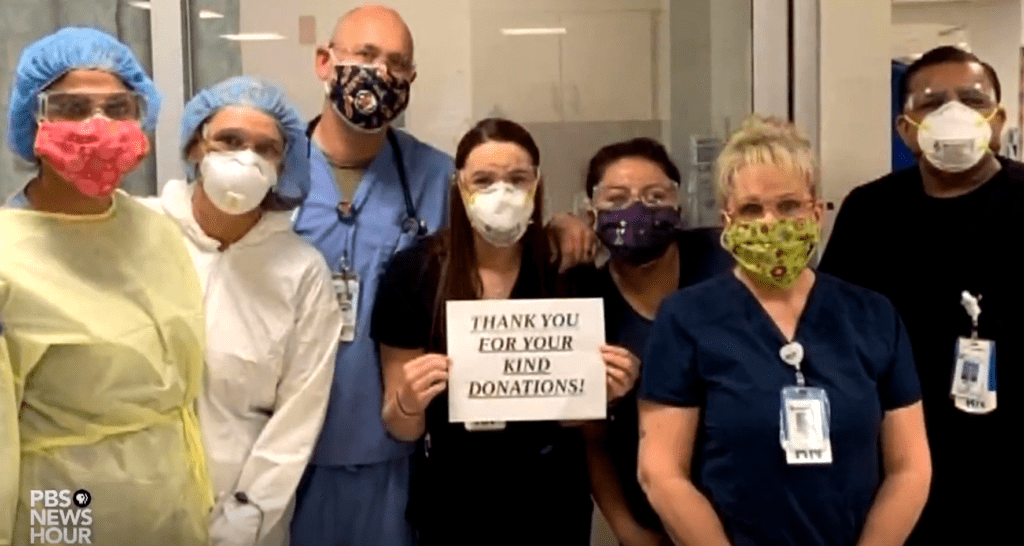

Body and spirit are inseparable. And so are their well-being. A doctor on the front lines of the coronavirus emergency was asked on NPR the other day about the value of simple, home-made face masks. You might have expected him to minimize their importance, since clearly they aren’t as effective as N95 masks in guarding against viral aerosol transmission. Instead, he spoke of their usefulness worn over N95’s, and, just as significantly, the value of their cheerful and varied colors and patterns to the spirits of those working in grim conditions of medical crisis.

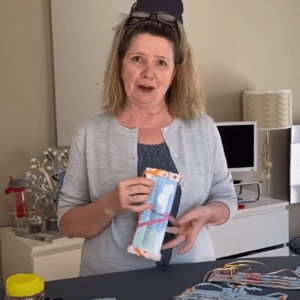

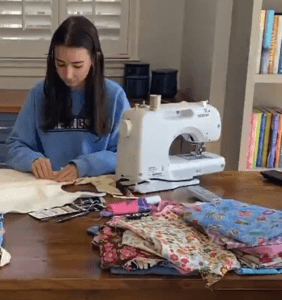

Yesterday, the PBS Newshour ran a story, about the people behind the masks—not the doctors and nurses but the mask makers. The story asks “what is motivating the small army of citizens making masks in their own communities[?]” One seamstress, Anya Caldwell (shown at left), said something that sticks with me:

Yesterday, the PBS Newshour ran a story, about the people behind the masks—not the doctors and nurses but the mask makers. The story asks “what is motivating the small army of citizens making masks in their own communities[?]” One seamstress, Anya Caldwell (shown at left), said something that sticks with me:

A personal message to the people out there that are obviously stressed having to do this right now that we care for them, we love them. Neighbors donated the fabric that 37 years ago were the curtains in their baby’s nursery. So they had sentimental value.

Body and spirit are stitched together with one word: care. Hearty spirit and skill combine in the efforts of medical professionals meeting this terrifying moment. Even the relentlessly “practical” doctor notoriously lacking “bedside manner,” doing his duty without a thought of what we call “sentimentality,” does his work with professional pride and thus, as we say, carefully. No less important to the sick is the spiritual care—the concern and empathy—provided by family and friends with perhaps no scientific or medical training, but who extend, if necessarily from a distance, abundant love and hope. But one wonders if it is, after all, even possible to practice the arts of medicine and health care (and they are, absolutely, arts) without both technical expertise and deep-down kindness—an indispensable combination shared by all the arts, including that of these home mask-makers.

Nor can we fail to see in this story the lesson of the service of two seemingly unconnected arts—sewing and medicine—to each other. It’s a reminder that all the arts have always and in myriad ways been interconnected and mutually helpful.

Nor can we fail to see in this story the lesson of the service of two seemingly unconnected arts—sewing and medicine—to each other. It’s a reminder that all the arts have always and in myriad ways been interconnected and mutually helpful.

The work of these mask-makers is the stuff of the social fabric. And that fabric is not mere metaphor. It is real—even sometimes literal—and we realize it every day in what we make and how we serve. And human beings have always understood the true nature of that fabric—or when we’ve forgotten it, have been reminded by such perennial crises of the social fabric as we’re experiencing now.

Linsey-Woolsey

In a post last year, Doug Stowe wrote of another time of struggle and hardship, and the humble but essential fabric it produced:

In the Ozarks there was a kind of material woven by early settlers, called linsey-woolsey. The warp was linen, giving strength, and the woof was wool, giving warmth, and to be woven into the fabric of community requires time, and effort to find one’s place among the threads.

In this time of social distancing (some have wisely suggested we switch to the term “physical distancing”), it is fascinating to see the human spirit made more acutely aware of its inherent and most primal needs and nature. We are seeing heart-warming expressions of an instinctive longing to overcome isolation, “to find one’s place among the threads,” and to seek ways to help stitch and weave back together, in linsey-woolsey fashion, a world under great stress and tension.

We are reminded of our nature, both as extraordinarily social animals and extraordinarily creative creatures—the two aspects of our nature, like body and spirit, inseparable and interwoven. Our powers to make are indispensable to the mutual provision and reciprocity that bind society together, and underlie, bolster and feed those feelings of common humanity—love and care—necessary to the human spirit.

The Fabric of the World

The Fabric of the World

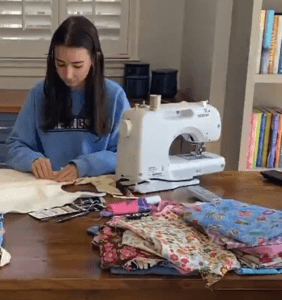

The most important workers in the world right now are the doctors and nurses and support staff treating coronavirus victims. But helping protect the lives of those crucial people are the loving hands of countless stitchers at home at their sewing machines. For all their heroism and kindness, and despite the news stories, the people behind the masks will remain largely anonymous.

That’s a truth that takes us back once again to ancient, eternal wisdom about the nature of humanity and care—charitas. It’s a truth expressed, for example, in Ecclesiasticus, which teaches us that human life and civilization depend ultimately on the ordinary, practical but nonetheless careful work of largely anonymous workers who are foundational and necessary to every community, on “every artificer and workmaster,” the metalsmith, the potter and the like—and no less so the doctor, nurse, and seamstress—who “put their trust in their hands; and each becometh wise in his own work. Without them shall no city be inhabited…” These folks may not gain much fame or notoriety: “they shall not be sought for in the council of the people, and in the assembly they shall not mount on high,” nor otherwise achieve reputation or office as political or religious leaders, scholars or teachers. But, says the scripture, “they shall maintain the fabric of the world; and in the handiwork of their craft is their prayer.”

Spirit and body are by nature one and interdependent. The goodwill of the spirit and the work of the hands remain securely and eternally joined to each other in our arts. And in turn, our arts join themselves together to weave and maintain the fabric of society and of true civilization.

The arts are care made real. The arts are how we join—and how we will re-join—the world.

More…

Doug Stowe has shared this video on how to make masks…

Check out Doug Stowe’s Wisdom of Hands blog…

Watch the Newshour story…

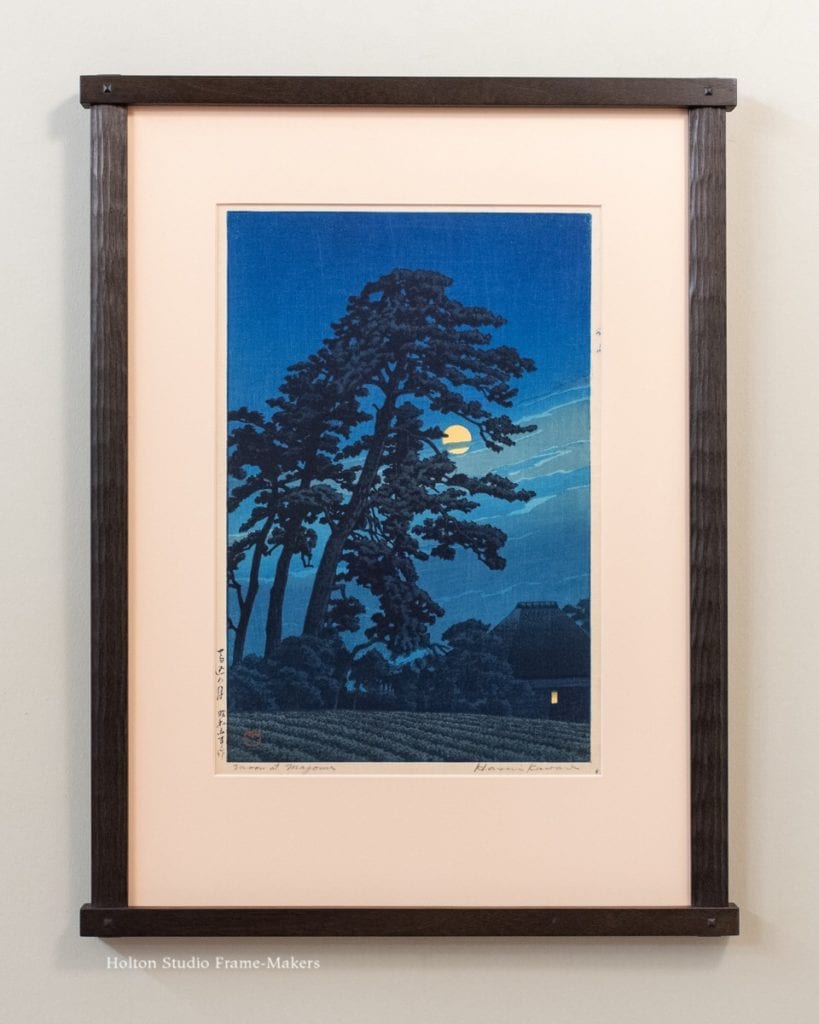

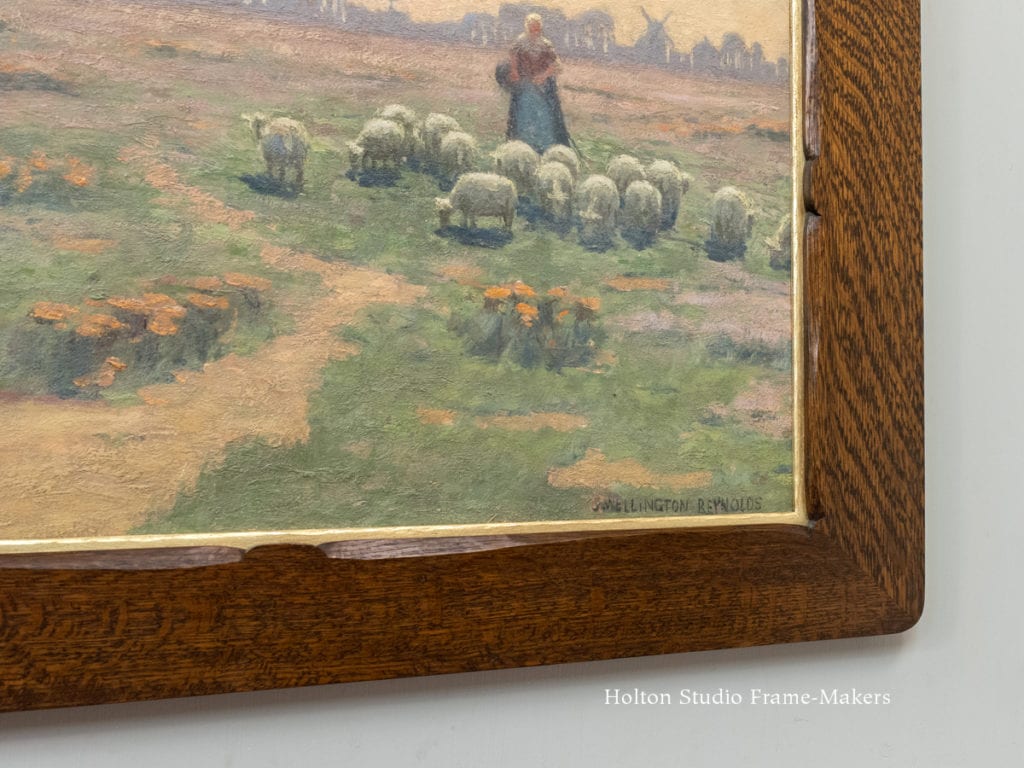

the third one below, the outset corners are on the narrower mitered inner molding that’s set inside a plain mortise-and-tenon flat. All are quartersawn white oak. All three are available through California Historical Design in Alameda.

the third one below, the outset corners are on the narrower mitered inner molding that’s set inside a plain mortise-and-tenon flat. All are quartersawn white oak. All three are available through California Historical Design in Alameda.