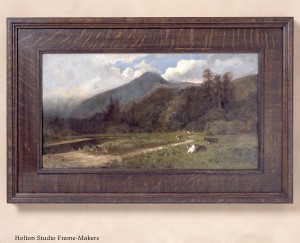

We just framed this large 40″ x 72″ oil painting by  William Keith (1838-1911), “Mount Tamalpais from the Northwest,” 1879. At right is how it came to us—in a fussy compo and metal leaf frame that has nothing to do with the mood of the painting. The bright setting pulls the eye away, especially undermining the shadowy foreground of the scene. Known as “dealer’s frames,” these were more about selling the picture, or, once in the home, impressing guests. The customer felt the work deserved something better.

William Keith (1838-1911), “Mount Tamalpais from the Northwest,” 1879. At right is how it came to us—in a fussy compo and metal leaf frame that has nothing to do with the mood of the painting. The bright setting pulls the eye away, especially undermining the shadowy foreground of the scene. Known as “dealer’s frames,” these were more about selling the picture, or, once in the home, impressing guests. The customer felt the work deserved something better.

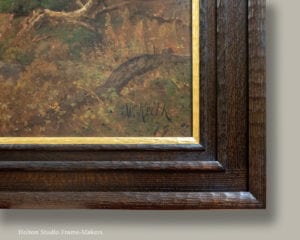

We made our very first cassetta frame many years ago for a much smaller Keith of the same subject, “Springtime, Mount Tamalpais,” 1888, shown at right. (I wrote about framing another Keith painting of Mount Tamalpais a couple of years ago here.) This one we just did (above) is 5-1/2″ wide, made in quartersawn white oak with Saturated Medieval Oak stain and a 1/2″ carved gilt liner. It was constructed by Trevor Davis and finished by Sam Edie.

We made our very first cassetta frame many years ago for a much smaller Keith of the same subject, “Springtime, Mount Tamalpais,” 1888, shown at right. (I wrote about framing another Keith painting of Mount Tamalpais a couple of years ago here.) This one we just did (above) is 5-1/2″ wide, made in quartersawn white oak with Saturated Medieval Oak stain and a 1/2″ carved gilt liner. It was constructed by Trevor Davis and finished by Sam Edie.

We augmented the basic cassetta form—a mortise-and-tenon joined flat flanked by inner and outer mitered moldings—with a sort of subordinate mitered molding in cassetta form inside of it, stepping down to add to the receding feel of the frame, lead the eye into the picture, and enhance its perspective. The rounded cushion forms echoing the oak trees and rounded hills are carved, as is the liner, and are complemented by the two flats which are not carved.

In the 1870’s Keith had become successful; in the year he painted this work he bought $10,000 in mining stocks. His promoters included his close friend John Muir, who once held up before Congress one of Keith’s Yosemite paintings as part of a plea to “preserve (the valley) in pure wildness for all time for the benefit of the entire nation.” The artist’s fame and fortune were also well-served by railroad tycoon Collis Huntington. According to Oscar Lewis’s charming and entertaining Bay Window Bohemia (1956), “Huntington, whose financial acumen was universally respected—and for good reason—maintained that Keith’s landscapes were not only highly decorative but were sound investments as well, and his often repeated advice to friends to ‘Buy Keiths’ was usually followed.”

By the 1890’s The City had a sizeable population of wealthy homes with their own art galleries, as well as lesser but aspiring and emulative households the furnishing of which would not have been considered complete without at least an oil painting over the fireplace. Given the pretensions of these homes, most of their paintings were from Europe. But, Lewis wrote,

Locally produced paintings were…by no means overlooked. Why, then…did the town’s group of highly competent artists have so much trouble finding buyers for their wares?

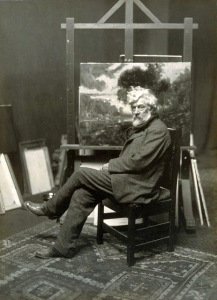

The answer to that question is simple. One San Francisco painter so far overshadowed his confreres in public esteem that for all practical purposes he had the field to himself. The man who occupied that enviable position was, of course, William Keith, the canny Scotch emigrant who had arrived during Civil War days, had worked briefly as an engraver, and in the early 1870’s—after a year of study at Dusseldorf—had opened his first San Francisco studio in the Mercantile Library Building at Bush and Montgomery streets.

His choice of that location—well removed from the Bohemian quarter at the other end of Montgomery Street—is of no little significance. From the beginning Keith was a staid businessman-artist, spending long hours daily at his studio and having no truck with the improvident, fun-loving painters, sculptors, and scribblers who nightly congregated in the cafes and bars on the lower fringes of Telegraph Hill. Keith’s friends and associates were all substantial citizens: bankers, lawyers, prosperous merchants, professors, and the like.

In his ascent, Keith moved in 1894 to a larger studio at 424 Pine Street above the California Market. Oscar Lewis’s account includes this amusing picture of the sales technique of the “businessman-artist” “at the height of his vogue”:

Throughout that period the method of acquiring a Keith was a solemn one, bearing little resemblance to an ordinary business transaction. One purchaser was so impressed that years later he vividly remembered the experience. On entering the studio he had found the artist at work in the big outer room, and to all appearances so absorbed as to be unaware of the other’s presence. After a period which the caller estimated to have been at least ten minutes, he had approached and made known his errand, whereupon the painter had laid down his brush and gravely led the way into the adjoining room.

Across one end of that chamber were a pair of black velvet curtains, behind which Keith stepped briefly, then reappeared and silently drew the curtains apart, revealing one of his landscapes on an easel, brilliantly illuminated by concealed lights. Having given the other several minutes in which to admire it, the artist drew the curtains, substituted another picture, and the process was repeated. Not a word was spoken during this ritualistic procedure until at length, having been privileged to see an even dozen canvases, the impressed caller made know his preference and asked its price. On being told the figure—$300—he counted out that sum and with his picture, carefully wrapped by Keith, under his arm, made his way to the shop of S.&G. Gump to have it suitably framed.

Like William Morris, Keith seems to have been one of those rare artists for whom business matters come naturally and don’t distract from or compromise the work itself, and admirers were by no means limited to collectors and conservationists. When George Inness came out from New York, Keith was in awe of the artist he once called “the biggest man in America”; yet the regard Inness gained for Keith was made evident by his nearly daily visits to Keith’s studio. The next generation esteemed Keith as well. In a letter to Keith from Paris, the very promising young painter Arthur Atkins (1873-1899) wrote,

My dear Mr. Keith:

I have been to the shows in New York—I have seen all the shows in London—I have seen the Louvre, every picture, over and over again, the Luxembourg too and I desire to tell you that I saw as great landscape painting in the studio of a man named William Keith out in California as any I have seen since. You may say I don’t know—all right, have it your own way. You’ll believe it some day—Corot, Rousseau, Daubigny, these are all great names, and they are hung for all the world to see in the Louvre, but they are not greater than yours. Heaven knows, Mr. Keith, I don’t want to make you conceited, but you are a great man, a great master of landscape. God bless you and keep you painting for many a long day yet…

Other posts on framing Keith are here, here, and here.

« Back to Blog

To Trevor and Sam: awesome work. It’s impressive to see a work of such size, must have been a backbreaker!

To Tim: awesome blog. It’s fun to read all of the William Keith knowledge that you’ve shared here.

“On entering the studio he had found the artist at work in the big outer room, and to all appearances so absorbed as to be unaware of the other’s presence. After a period which the caller estimated to have been at least ten minutes, he had approached and made known his errand… Having given the other several minutes in which to admire it, the artist drew the curtains, substituted another picture, and the process was repeated. Not a word was spoken during this ritualistic procedure until at length, having been privileged to see an even dozen canvases, the impressed caller made known his preference…”

Potentially a new Holton Studio business model?