Just completed this wonderful small painting by one of our region’s very greatest landscape painters, William Keith. Finishing this little piece coincides nicely with a talk here tomorrow by a contemporary artist, Paul Roehl, who has been very much inspired by Keith. Paul’s lecture will frame art and nature in a talk titled “Naturalism and Transcendence in Contemporary Painting”. More about that on Paul’s page here…

Paul’s a gifted and popular art and art history professor here in the Bay Area, and so shares with Keith a talent for speaking on art. I found some wonderful quotes by Keith in Brother Cornelius’s biography of the artist, Keith: Old Master of California (1942), and share them below.

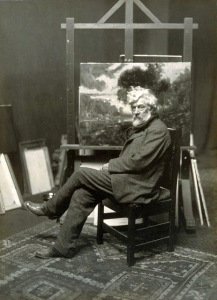

William Keith (1838 – 1911), untitled California landscape, 1896. Oil on board, 5″ x 7″. The simple 1-1/2″ wide scoop is in quartersawn white oak frame with Dark Medieval Oak stain, and has a gilt oak slip.

Keith on Art and Nature—

As a student in Europe in the 1870’s, Keith (1838-1911) wrote a letter from Dusseldorf to a close friend back in Keith’s hometown of San Francisco. The letter speaks profoundly of Keith’s aspirations and ideals. He was especially impressed by exhibits of painting in Paris, and the direction it pointed him in in contrast to what he found at school in Germany. And yet its lessons of a vital and personal art, free from hollow “style” and convention (although inspired by tradition) and determinedly—passionately—rooted in nature, turned his eyes finally back to the incomparable landscape of his adopted home in northern California:

“The French are Big things… If the exhibitions in Paris were permanent I should go there and study, but as they only continue for a month and Paris being far from nature, why[,] I remain here, but not for long. I have been gradually coming to the conclusion which I shall put into execution in the fall[,] and in Paris I fully made up my mind that it was the only thing for me to do. I mean that I am going to study altogether from Nature—you know that if there is anything I want to be it is to be original and when I came back [to Dusseldorf] from Paris and saw my pictures, and the ones here in the galleries, I saw that I had been unconsciously falling into the German style that I am going to get rid of and the only way to do that is by studying nature. I will have learnt a good deal by Fall and intend to go down in Maine and study for a year. After that I shall go back to Cal. for I feel that S.F. is my home. I can’t give you all my reasons for this but I am sure you would uphold me if you were here and had my experience. I tell you…that the schools are the places for machines of a higher class than they have with us, but a man who has the artistic instinct strong needs only nature,—to learn to do the things in a certain way ties the mind to that way, and one never can fairly break from it. As for me I can do it by myself and with nature this particularly applies to landscape… [M]ost people think that if one is in a European school they get the art of painting poured into ’em in a mechanical kind of way…. What’s wanted is capacity—opportunity is everywhere. I don’t mean to say that it isn’t a good thing to come here. If I hadn’t seen these pictures, I should never have had the ideas I now have, but I have learnt to look at nature with different and more intelligent eyes—that’s the advantage to see Nature… I don’t intend to sit down and be a mediocre painter.”

Keith on Art—

Keith clearly had a charming way with words, and in later years, having achieved considerable fame and fortune in San Francisco, he became a sought-after lecturer. In the mid-nineties, about the time this painting was done, Keith spoke to a small gathering in his Pine Street studio. He led off with a story to make the claim that he’d rather die than lecture—but in so doing betrayed a winning and engaging sense of humor that any public speaker would admire:

Some years ago I gave a lecture before the University of California. It was a lecture on Art, and I had to consult a great many books and make extracts which took a great deal of time and much anguish of mind to patch them together in order to make it appear that it was all original matter—this is the way, I believe, that art lectures by artists are gotten up—and not being used to literary work and the scissors, the anguish of mind I endured while getting it up was only equalled by what I suffered in its delivery. The day of the great event was significant, for the Lecturer’s house got on fire and to the regret of the lecturer he an his lecture were not burned together. The fire was extinguished and I had to go and meet the audience. While sitting in a side room waiting for the signal to mount the platform, there was a slight shock of earthquake; not big enough, however, to scatter that audience. I vowed then and there never to appear before an audience again.

With the same humor he grappled with the difficult subject of what art is:

Art is a pretty big subject to talk about and hard to define. Did you ever hear Turner’s definition?—he was in company with an enthusiastic woman, at one of Ruskin’s lectures—and going home after the lecture the great man’s admirer tried very hard to get Turner to say what he thought of Art. When they were about to separate Turner said, “Well, I’ll tell you what I think of Art. Art is a queer business.” And so it is. People have very hazy ideas about it sometimes, but the haziest idea of its practical workings, I know of, was of a man who came into my studio one day and said that he had just got out of the County Hospital, was hungry and wanted to get money enough for dinner. In going out he had to pass through another room where I had a few young lady pupils. After he had gotten into the passage-way leading from this room, one of the young ladies said to me that he would make a good model and that I ought to get him for a model. I went after him and told him that the young ladies would like to have him come and sit for them and that they would pay him six bits or a dollar for sitting an hour or so. He asked what he would have to do.

“Oh,” I said, “just sit up in a chair and they would paint you.”

“Paint me!” said he.

“Yes.”

“Well, I don’t know; how would I get the paint off me?”

These stories reveal a lovely soul behind the work, and allow us to admire it all the more.

We hope you can join us for Paul Roehl’s talk, “Naturalism and Transcendence in Contemporary Painting” tomorrow at 4:30, here at The Holton Studio Gallery.

See my blog post on a painting Keith did while in Yosemite with John Muir...

More Keith paintings we’ve framed are here, here, and here.

« Back to Blog

Paul Roehl liked this on Facebook.

Daniel WK Chow liked this on Facebook.

Karen O’Mara liked this on Facebook.