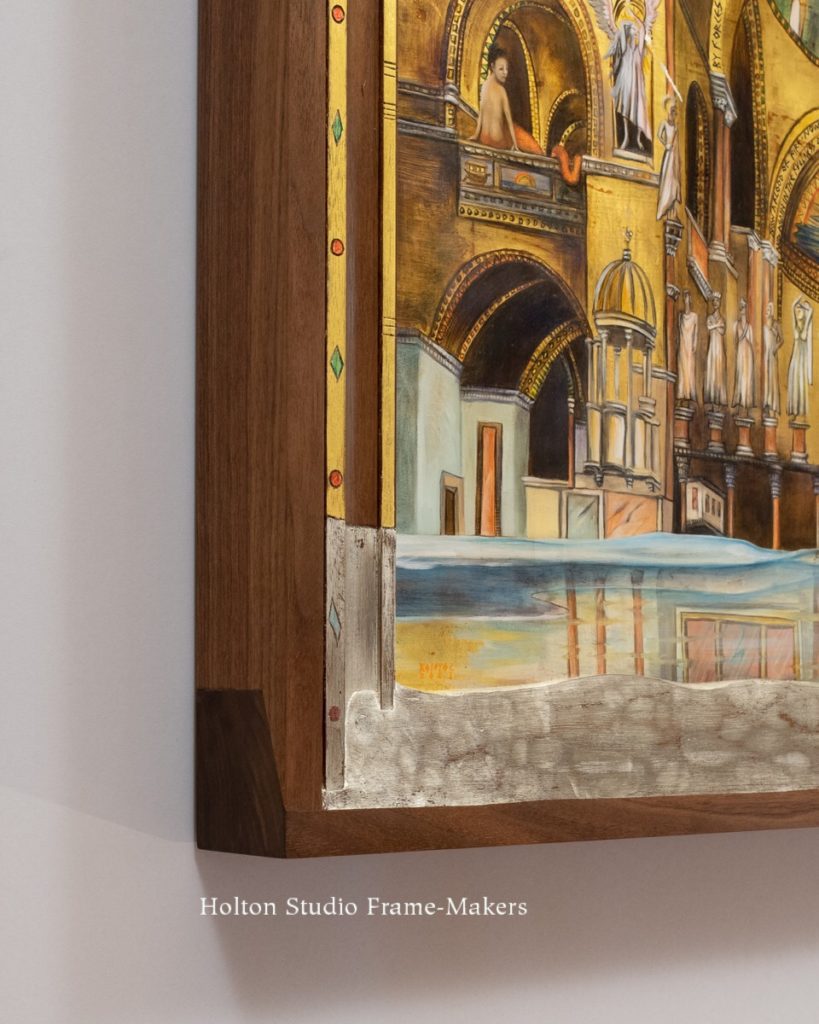

In my last post, here, I introduced sill frames, featuring one we made for Karima Cammell‘s “Atlantis,” an impressive egg tempera painting included in our current solo show “High Water.” I pointed out how I carved the frame’s beveled bottom rail—the sill—with a simple pattern extending out from the painting the masonry seams in the stone floor of the room the painting depicts. The sill frame for another painting in the show, the dramatic “Aqua Alta,” featured here, also extends the image’s foreground, which in this case is that unsettling element from which both the show and the painting draw their titles (actually the same term in different languages).

Karima Cammell, “Aqua Alta,” oil and 23.5kt yellow & 12kt white gold on linden board, 18″ x 24″. Sill frame in walnut with white gold and 23 kt gold and oil paint.

If the goal of harmony and unity are to be reached, architecture in a picture is always and naturally a cue for the architecture of the frame (which I think of as architecture at its most refined).  This painting of the spectacular gilded interior of St Mark’s Basilica as filtered through Karima’s extraordinary imagination—which also transformed the painter herself into a mermaid in order to adapt to Venice’s increasingly frequent flooding (called by Venetians the “aqua alta”)—presented a clear frame-making challenge, and one for which the highly architectural sill frame genre seemed to me ideally suited.

This painting of the spectacular gilded interior of St Mark’s Basilica as filtered through Karima’s extraordinary imagination—which also transformed the painter herself into a mermaid in order to adapt to Venice’s increasingly frequent flooding (called by Venetians the “aqua alta”)—presented a clear frame-making challenge, and one for which the highly architectural sill frame genre seemed to me ideally suited.

The frame is 2-5/8″ wide (and just as deep, to accommodate the painting’s support, a heavy solid linden wood panel with dovetailed oak battens to keep it flat), and made of walnut with a clear oil finish, with 23 kt and white gold and paint. For the molding profile, I distilled the combination of arches and bands of molding in the painting to a fairly simple profile: a cove bounded by two gilded flat straps.  The straps are carved, the inner one to extend the architectural details of the painting where they meet the frame, and the outer one painted with a simple pattern of alternating red circles and green diamonds echoing patterns in the moldings. Where the painting most dramatically spills (literally) into the frame, of course, is at the bottom and foreground, and that’s where I took advantage of the sill. The water line is carved into the sides of the frame, and from that line down the sides and sill are leafed with white gold. I cut and chamfered the sill lip in a wavy pattern, and carved the face of the sill in soft, water-like undulations.

The straps are carved, the inner one to extend the architectural details of the painting where they meet the frame, and the outer one painted with a simple pattern of alternating red circles and green diamonds echoing patterns in the moldings. Where the painting most dramatically spills (literally) into the frame, of course, is at the bottom and foreground, and that’s where I took advantage of the sill. The water line is carved into the sides of the frame, and from that line down the sides and sill are leafed with white gold. I cut and chamfered the sill lip in a wavy pattern, and carved the face of the sill in soft, water-like undulations.

One thing I love about sill frames is how the molding profile of the side members intersects the sill, creating the illusion of door frame moldings or columns of a building meeting the floor.

Except the sill is not simply a floor but a threshold—a word of great significance to Karima’s beloved Venice and it’s brilliant cathedral in an age of rising sea levels, and also descriptive of the transformational age we live in. It is also, as we’ll see in a later post, a word profoundly significant to the art of the picture frame—the frame’s efficacy and transformational power.

In any case, I cannot end this post without acknowledging the kindness of Karima Cammell, a painter who welcomes and encourages the artistic collaboration of her frame maker, and so keeps alive the cooperative ethos of medieval artisans immortalized in the stones of Venice and its great basilica.

Process photos—

- One of the top corner joints

- The mortised sill, ready to carve

- The sill joint going together

- The left sill joint after oiling, but before gilding, as the frame is checked against the painting

View “High Water: Works by Karima Cammell” online…

Read “Sill Frames—I: Framing Karima Cammell’s ‘Atlantis'”…

Read “Sill Frames—III: Framing Karima Cammell’s ‘Fire With Fire'”…

« Back to Blog