Today, North Point Gallery’s show “Historic Artists of the East Bay” is opening, and as I said in my last post, we framed a number of paintings included in it, like the Edwin Deakin I wrote about.  Another painting we framed for that exhibit is by Oakland painter Henry Dietrich (Dick) Gremke (1860-1939), son of German immigrants and California pioneers who arrived in San Francisco shortly after the Gold Rush. Dick Gremke would settle in Oakland.

Another painting we framed for that exhibit is by Oakland painter Henry Dietrich (Dick) Gremke (1860-1939), son of German immigrants and California pioneers who arrived in San Francisco shortly after the Gold Rush. Dick Gremke would settle in Oakland.

We’ve framed Gremkes before, one of which, shown at right, I wrote about a year ago, here. (Replacing that particularly hideous gilt frame was especially rewarding!) That one’s in the same show, in fact, along with a third Gremke shown at the bottom of this post, also framed early last year.

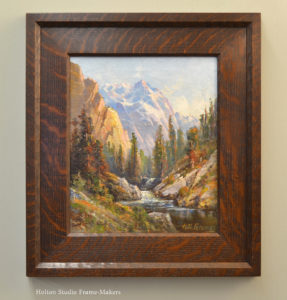

This small one (9-3/4″ x 13-1/2″) we just framed is titled “Logging in California,” n.d. (ca. 1890). North Point’s Alfred Harrison’s provides the following commentary:

H.D. “Dick” Gremke was born in San Francisco and studied landscape at the California School of Design under R.D. Yelland. From his studio in Oakland, Gremke took sketching trips in the summertime to the Sierra Nevada, painting Kings River and Yosemite scenery. He is best known today for his painting Camp Teller in the Kahn Collection of the Oakland Museum. Camp Teller depicts the little railroad that transported redwood lumber from the Santa Cruz Mountains near Glenwood. Our logging scene shows a view in the redwoods, with oxen pulling huge logs over a road that is planked with railroad ties. It is a rare view of nineteenth-century California industry, as well as a beautiful little painting with a unified palette of related brown colors.

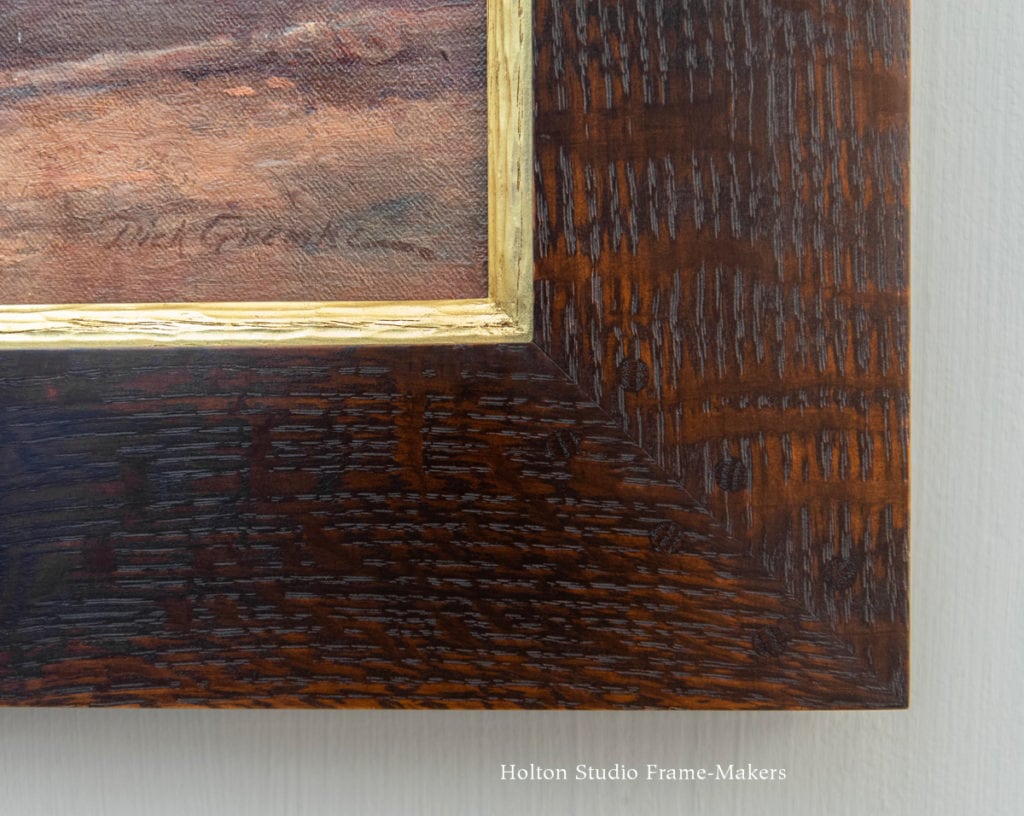

Corner detail of the No. 1—3″ frame. The six dowels at each miter joint pin the spline, a triangle of wood running through the joint.

The painting called for an even plainer treatment than the previous two—a 3″ wide No. 1 in quartersawn white oak, with Dark Medieval Oak stain to carry out, sustain and amplify that harmonious palette of browns Alfred rightly admires. There is a simple embellishment that I’m especially pleased with: the sets of dowels at each miter joint. The joints are splined (a triangular piece of wood, the grain running perpendicular to the 45 degree miter, is glued in to a slot cut through the joint), as all our miters are, so the dowels further strengthen the joint by pinning it. Because those oxen are strong and might bust out of the frame if it’s not built to take the force. There’s a visual benefit to this detail, which is the way it echoes the cut ends of the small logs laid across the road as well as those of the large logs on the other side of the road. The painting is, after all, about logging. All a frame really needs is one little touch like this to make it alive to the picture it’s created to serve. “The frame is the reward of the artist,” Ingres said (not Edgar Degas, though the statement’s usually misattributed to him); and that’s in large part because the design and making of the frame reflect the fact that the artist has succeeded in helping at least someone see, and protect and care for and about, what he or she wanted the world to see and care about. To take that task—and that responsibility—seriously is to take seriously the frame and the art of the frame-maker.

We hope the wood being hauled away is put to good use, building things, like this frame, made to last at least as long as it takes new trees to grow. A carved and gilded beveled liner elevates and emphasizes the painting, and the window, left to us by Gremke, on the tremendous labor and sacrifice it takes to work with nature to provide the materials to build and furnish our homes, towns and cities.

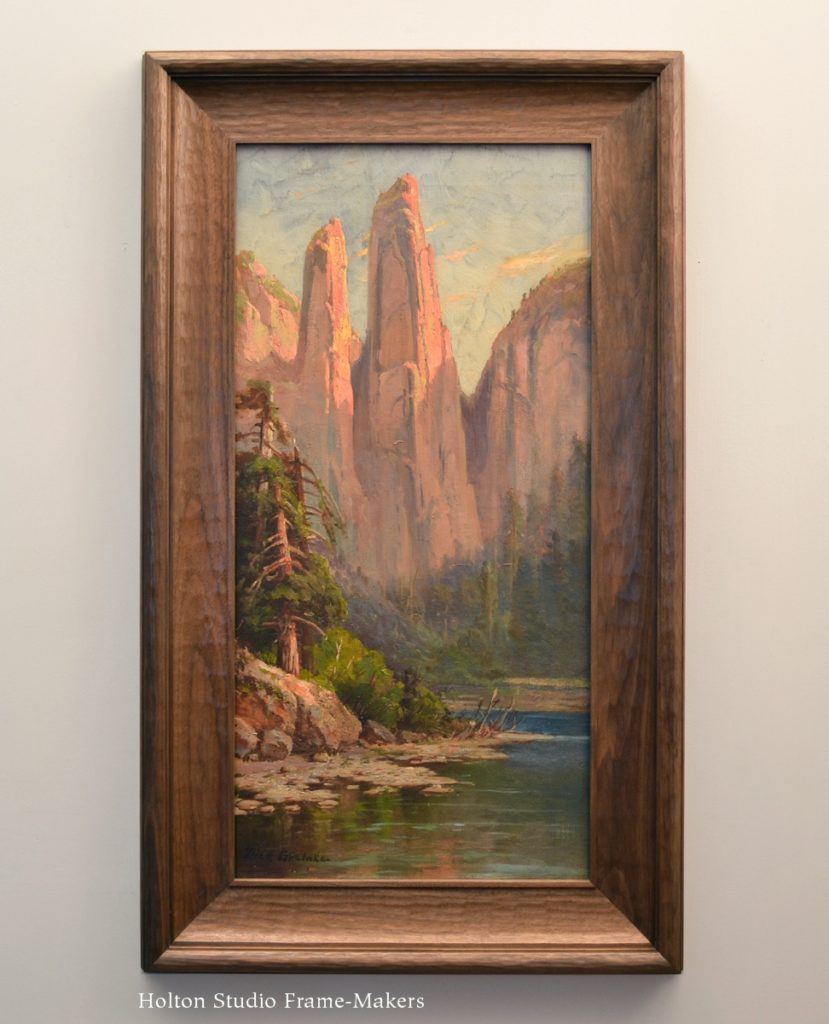

Here’s the third Gremke, “Cathedral Spires, Yosemite,” n.d. (oil on canvas, 28″ x 14″) also in the North Point Gallery show opening today:

H.D. Gremke, “Cathedral Spires, Yosemite”, n.d. Oil on canvas, 28″ x 14″, framed in Compound frame No. 301 CV + Cap 411 CV in walnut.

« Back to Blog