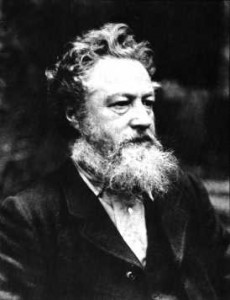

“Art is the expression of man’s joy in his labor” — that’s how the great material task of humanity and civilization was framed by William Morris. (Yes, it was Morris — not, as a Google search will lead you to believe, Henry Kissinger). After reading Peter Schjeldahl’s New Yorker piece, “All Is Fairs” , it’s clear to me the thought is long overdue for rewriting. How about this: “Art is a few people’s expression of their joy in seeing how much money they can get the .000000001% to spend on kooky and ever-so-cleverly-ironic stuff they make, or find, or kind of throw together, or whatever.”

Art fairs, the cutting edge of the self-proclaimed cutting edge art world, are now so baldly and purely mercenary that uber-collector/”gallerist” (that would be a proponent of gallerism, the belief that the true place of art is not in the home but insulated from real life through relegation to art galleries where it can be properly cultivated) Larry Gagosian wouldn’t even bother to get out of his chair to greet populist emissary Morley Safer and the “60 Minutes” crew who showed up recently at his booth at a fair to find out if the scene’s really as crass and vapid as it appears. As Schjeldahl reports the incident, “‘It is a place to make money,’ Gagosian allowed languidly.” Yep, it’s really as crass and vapid as it appears.

Schjeldahl’s one of the elite, one of the critical — as in “crucial” not as in “ready and willing to criticize” — critics the “Art World” depends on to cover it in otherwise intelligent journals and build up an otherwise dubious legitimacy (for the “Art World” if not for the journals). But his appreciation of art at least once in a while reveals authenticity, enough so that he sizes up current art fairs with the conclusion: “a spiritual gulf steadily widens between the people who buy art and those who only love it.” Of course, the truthfulness of that statement depends on how you frame your understanding of art.

But at least as Schjeldahl frames it, the long story of the separation of art from daily life and labor goes on, at least within the pure white walls of art fairs, deaf as ever to William Morris, blind as ever to 99.99999% of those of us who go on making things to express their joy in their labor.

Thanks for allowing me an occasional rant.

And thanks for asking.