We’re finishing up hanging the Richard Lindenberg exhibit which starts tomorrow. There are several I have a hard time taking my eyes off of, including this little set of three, each one just 6″ x 6″.

I like framing sets of pictures in frames that, like the pictures, are different but similar—variations on a theme.

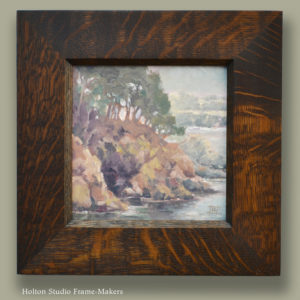

Richard Lindenberg, set of three small California landscape paintings, each 6″ x 6″. Oil on linen on panel. (Left to right: “Marsh Colors,” “Russian Gulch Fog,” and “Pacheco Marsh.”)

In this case, the frames are all stained quartersawn white oak, 2″ wide, and are basically the simplest possible profile, which is our No. 1, but with a simple carved element at the sight edge. The variation is in the shape of that element. We chose a form that in each case is specific to the picture and alive to its individual character—for “Marsh Colors,” a quarter-round relating to the shape of the trees; for “Russian Gulch,” a chamfer echoing the steep rocks; and for “Pacheco Marsh,” stepped parallel bands to resonate with the receding pattern of little deltas.

These simple profiles—often flats, but also slopes, coves and cushions—with a carved sight edge have become one of our mains stocks in trade. Apart from the shape of the element, the carved surface works in several respects:

- the texture of the carving echoes that of the brushwork;

- the texture also echoes the irregular surfaces of things depicted, like rocks, tree trunks, water, etc.;

- it creates a surface that the light dances off of, enlivening the play of light around the painting’s edge, catching

attention to the picture and giving it emphasis;

- it’s a bit of hand craft, and a painting is a bit of hand craft as well;

- it reveals the nature of the wood, giving us a sense and appreciation of the character of the material—its density and hardness, etc.;

- it softens the transition from the texture of the canvas to the smooth main portion of the frame and the wall;

- it’s in keeping with the rustic spirit of the picture;

- with respect to the design of the frame itself, it’s a complement to the smooth portion.

In these key ways, the frame sustains the spirit of the picture and helps connect it to the wall. And by this approach to framing them, three very different paintings, though sympathetic in palette and general subject matter (the rural California landscape), connect to each other and are presented “of a piece.” It’s part of the task of joinery that is the true business of the frame-maker, connecting different arts, varied works, to each other; painting to architecture and to the home—the architecture of daily life. Such joinery, bringing together varied pictures, fulfills an eternal wisdom echoed down to us by many, including Walter Crane, when he wrote, “I know no better definition of beauty than that it is ‘the most varied unity, the most united variety.'”*

*The Claims of Decorative Art, 1892. Crane was the first president of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society.

« Back to Blog