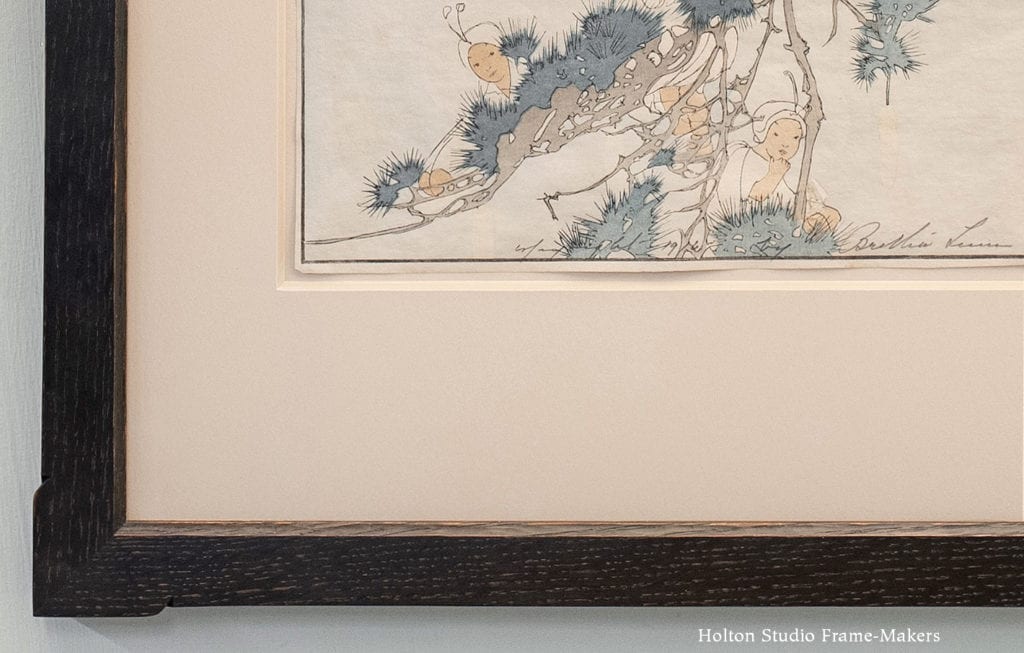

Here’s a delightful block print by Bertha Lum (1869-1954), which came through the shop recently. The image is about 16-1/2″ x 9-1/2″. It had been trimmed closely, without enough margin left to cover even a tiny bit with a mat, so we floated it in the opening of an 8-ply mat. The 1″ frame is stained quartersawn white oak with a carved chamfer at the sight edge and outset corners articulated with simple carved cuts (see detail of similar frame at bottom of page).

A frame is a window. That’s one of the keys to its transformative effect on a picture. A window lets the outside world in and the inside world out. A window lets in things like light and fresh air, and also visible things that exist beyond the wall and outside the window. A window also lets out things like stale or bad air from inside the building, and also the psychological equivalents of those—our mundane preoccupations, and our dark worries and fears. We turn to the window to dream and wonder. Where do we instinctively look when we daydream? Out the window.

A frame is a window. That’s one of the keys to its transformative effect on a picture. A window lets the outside world in and the inside world out. A window lets in things like light and fresh air, and also visible things that exist beyond the wall and outside the window. A window also lets out things like stale or bad air from inside the building, and also the psychological equivalents of those—our mundane preoccupations, and our dark worries and fears. We turn to the window to dream and wonder. Where do we instinctively look when we daydream? Out the window.

One of the main things the human power of imagination does is penetrate, and in that sense it works like a window. A picture, as a work and exercise of imagination, is an imagined window. No less than an actual window, the window that is a framed picture lets things in and lets things out.

The pictorial artist needs the window to express (the word means “press out”) his or her vision, and thus penetrate it—and penetrate the worlds of other people. We need the windows made by artists like Lum for our own vision to transcend the confines and boundaries of our enclosed, immediate world—to penetrate the wall and access the free air of imagination and possibility offered by a depiction of a world beyond our own shelters.

Resembling the trim around an actual window, a frame has the powerful ability to complete the illusion the artist has made of a scene beyond the plane of the wall. This is one of the main reasons for the transformative effect even the simplest frame has on a picture. If the picture’s an imagined scene, the frame is real. So it makes the imaginary vision a more engaging and credible possibility. Frames, then, literally realize dreams, and give them integral material place in our daily lives.

Resembling the trim around an actual window, a frame has the powerful ability to complete the illusion the artist has made of a scene beyond the plane of the wall. This is one of the main reasons for the transformative effect even the simplest frame has on a picture. If the picture’s an imagined scene, the frame is real. So it makes the imaginary vision a more engaging and credible possibility. Frames, then, literally realize dreams, and give them integral material place in our daily lives.

Of all the features necessary to a building, I would list after a roof and walls to hold up the roof, and a door to enter and exit through, a window. Even for the sake of basic security, a window is a necessary penetration allowing inhabitants of the building to see, from inside their protective walls, possible outside threats. The window thus offers both protection and prospect—twin primal human longings pictorial artists often tap into. But certainly for the well-being of the human soul, which craves light and enlightenment, a window is an undeniable necessity.

In the twentieth century the idea took hold that a frame represents limits and boundaries, and was thus an enemy of the freedom of the human spirit. Nothing could be further from the truth. Frames, being windows, penetrate constraining and limiting walls, free our vision, and gain us access to possibility. Far from being the enemy of the picture, the frame completes the picture’s purpose of offering penetrating vision.

Bertha Lum was born in Iowa but dreamed of going to the Far East and learning the art of the block print that the Japanese had mastered as an inexpensive pictorial art form that would make available to ordinary homes windows of the imagination. Her dream came true, and in fact she spent much of her adult life in Japan as well as China. She first went to Tokyo in 1903 for her honeymoon and wasted no time exploring the city in pursuit of her artistic longings. But facing cultural barriers, Lum found obtaining instruction in block printing very difficult. “Everything in Japan is very easy for the tourist” seeking souvenirs, she recalled, “but if you want something of the people, learn an art or buy something purely Japanese, you face a wall. There are no openings, it is too high to go over and if you try to walk around you only go in a circle and soon return where you started.” But with perseverance and her dream clear, she penetrated the wall to find willing instructors and collaborators and discovered the techniques of the trade. She would become one of America’s most notable practitioners of the art of the Japanese woodblock, giving Americans a window through the superficial wall of the tourist’s typical experience of the Far East—a window into the authentic culture.

In this print, Lum’s vision and imagination also penetrate to the world of fairies, whose unseen presence might account for the mysterious activity, strange plays of light, that a walker in the woods frequently senses but never quite sees. Through the window made by Bertha Lum, birds and luminous fairies may fly in. Or our own flights of fancy may fly out—to fresh air and light and other worlds, and be rejuvenated.

Below is a corner sample of a similar frame, this one in walnut, in which it’s easier to make out the corner detail. The customer and I liked how it imitates the form of the swallows. I like to have carving on frames for woodblock prints because it brings the method of making the woodblocks in to the frame and thus contributes to the harmony between picture and frame.