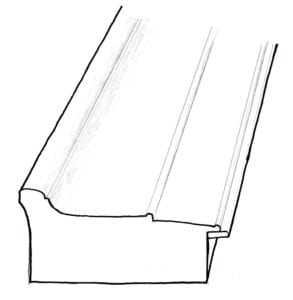

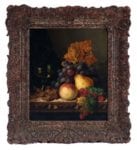

This is a still life by Ellen Ladell (1853-1928) we just re-framed. The frame is a compound No. 348 + Cap 408 at 3″ wide, in quartersawn white oak (Saturated Medieval Oak stain) with a gilt slip.

Little is known about Ellen Ladell other than that she was a student of Edward Ladell’s before marrying him. She was 25, he was 57. She so emulated her teacher that her work is hard to distinguish from his. It’s been suggested that many of their paintings were collaborations.

We framed a pair of Edward Ladell (1821-1886) paintings years ago (see below), and the clients for the recent Ellen Ladell piece saw no reason to devise a different frame for this one. Given the extraordinarily fine detail of these paintings, the challenge in framing them is not unlike that in framing a delicate etching or pen-and-ink drawing, the detail of which calls for the complement of the surrounding blank space that a mat provides. In this case, the oil painting on canvas has more weight than a print or drawing on paper, so can be framed close as paintings usually are, but is enhanced far better in a relatively plain profile than in the extremely busy period frame it was in. And once again, unlike gold, the shadow-like dark wood, by its complementary relationship to the light rendered so diligently by the painter, enhances that light.

We framed a pair of Edward Ladell (1821-1886) paintings years ago (see below), and the clients for the recent Ellen Ladell piece saw no reason to devise a different frame for this one. Given the extraordinarily fine detail of these paintings, the challenge in framing them is not unlike that in framing a delicate etching or pen-and-ink drawing, the detail of which calls for the complement of the surrounding blank space that a mat provides. In this case, the oil painting on canvas has more weight than a print or drawing on paper, so can be framed close as paintings usually are, but is enhanced far better in a relatively plain profile than in the extremely busy period frame it was in. And once again, unlike gold, the shadow-like dark wood, by its complementary relationship to the light rendered so diligently by the painter, enhances that light.

The complementary principle is also at work in the profile, which combines wide spacing with fine beads; and also, at the outside of the face, a cove bound by an ovolo dropping down to a cove, which is also complemented by the convex or cushion form at the inside.

Below is the Edward Ladell re-framed a decade ago (and posted on the blog here).

- Edward Ladell, before re-framing

- Compound No. 348 + Sub 408 on Edward Ladell oil painting

To jaded modern eyes, the Victorian still life paintings of the Ladells exemplify stuffy Victorian domesticity. Yet they seem to me oddly current all of a sudden in our time of pandemic. Because, what else are they than the products of lives in domestic quarantine during what John Ruskin famously called the “Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century”—”or more accurately plague-cloud,” as he himself clarified in the opening of the 1884 lecture. In truth, there wasn’t actually a quarantine in response to the plague of industrial smoke that so alarmed him—at least not as we know quarantining today. But there was certainly, for those with means, a quarantine-like retreat and escape to domestic life, as death and social corruption stalked the British population.

Note in the Ellen Ladell piece the masterful reflection in the bell jar—a glimpse through a window, the brick building across the street just discernible. It’s a favorite device of the artist’s and a detail that underscores the domestic setting. The entire still life genre is in fact shaped by and directed at (as a market) that domesticating trend of the modern era—a trend most highly developed by the Dutch merchant class that burgeoned in the seventeenth century and first established the still life genre.

Note in the Ellen Ladell piece the masterful reflection in the bell jar—a glimpse through a window, the brick building across the street just discernible. It’s a favorite device of the artist’s and a detail that underscores the domestic setting. The entire still life genre is in fact shaped by and directed at (as a market) that domesticating trend of the modern era—a trend most highly developed by the Dutch merchant class that burgeoned in the seventeenth century and first established the still life genre.

But the implications of the genre were more complex than simply domestic burrowing and hiding from the perpetual pall of smoke and madding crowd. The preserving bell jar itself, domicile to stuffed birds, seems to reflect also an understandably conservative effort to preserve the beauty of nature in the face of a destructive age. While such paintings represented colorful abundance and plentitude that households could at least aspire to, they also reveal an intense sense of the fragility of life—fragile as a glass dome, the domestic bubble—and, striking the theme of the subgenre of vanitas, even a recognition of the vanity of riches when death is certain and even near. Along with an explosion of material abundance, the Dutch Golden Age also knew plague. Thus the genre resonated in nineteenth century Britain—and for identical reasons might resonate with us today.

Jan Van Brueghel (1568-1625), “A Bouquet of Flowers in a Decorated Vase” (New York Times)

What’s enduring and admirable in the work of the Ladells is their faithful rendering of nature—albeit nature literally cut off from its source in order to be domesticated, but preserved lovingly in paint, at least. As it did for the Dutch Masters, the genre offered the Ladells the opportunity to display their mastery of painting skill. And it did indeed find an appreciative audience. An obituary for Edward Ladell noted that he was “the foremost man of his day in fruit painting.” One piece of Edward’s won this praise from a critic:

“[T]here is among the oil paintings, a little gem by Mr. E. Ladell, which has just been exhibited at the Royal Academy. Mr. Ladell’s ‘Prawns’ is deservedly admired for its realism and its exquisite finish. The prawns themselves are quite tempting; and the manner in which the artist has succeeded in expressing the shades and reflections in the tinted wine glass and its contents is especially to be noted.” (Source)

We may chuckle at the old criteria, but again, the fragility of life, especially for artists in the midst of the industrial revolution—one the son of a coach-builder, the other the daughter of “a smith and machine minder”—made them highly vulnerable to labor displacement and upheaval. Seems likely that much of the motive for the painter of such work was to secure prestige and a reputation by proving supreme skill, and in the service of a high reverence for nature, that no machine could possibly match. The result was a monastic sort of undertaking, not unlike the lavishly detailed illuminated manuscripts of medieval monks. And every bit as devotional.

As is so often the case with nineteenth century framed paintings, the workmanship of the factory-made period frames often found on the Ladells’s work makes them absurdly incongruous juxtaposed to the expert skill of the paintings, and therefore fails in their service to them. In the Dutch painting shown above, the frame—a great example of the ebony cabinetmaker’s frames that were at their peak in the Dutch Golden Age—is as beautiful and well-wrought an object as the vase and of a piece with the painting as a display and celebration of human skill and judgment. If the Ladells sought to escape the “plague-cloud” of their time, they succeeded just barely. It was literally and visibly closing in on them; the misery of industrialization encroaches right up to the paintings. Their frames (other Ladells in period frames at left and below) are exemplary of the “makeshift” production of the terrible industrial factory system that had devoured the sound creations of the old workshop system.

cabinetmaker’s frames that were at their peak in the Dutch Golden Age—is as beautiful and well-wrought an object as the vase and of a piece with the painting as a display and celebration of human skill and judgment. If the Ladells sought to escape the “plague-cloud” of their time, they succeeded just barely. It was literally and visibly closing in on them; the misery of industrialization encroaches right up to the paintings. Their frames (other Ladells in period frames at left and below) are exemplary of the “makeshift” production of the terrible industrial factory system that had devoured the sound creations of the old workshop system.

By wiping out that system, industrialization wiped out the art of the frame-maker. Frame production was relentlessly mechanized. The joinery was cheapened and weakened. The carver, once the inseparable friend and collaborator of the painter, was reduced to putting himself out of work by carving molds for overwrought patterns made to cast the hard plaster called composition—fake carving applied to a cheap deal frame. By the time of the Ladells, the art of the frame had reached its absolute nadir, a degradation and offense to so many masterful paintings, giving justification to the twentieth century’s categorical exile of frames.

In any case, the emphatic and impenetrable boundary was drawn around pictures alone as Art. The frame was decidedly not.

- Ellen Ladell

- Edward Ladell

- Edward Ladell

- Edward Ladell

Fantastic as always Tim. The degradation of art in the service of what is cheap. And yet your use of art to enhance another kind of art – the frame for the sake of the picture. Perhaps this is a model for any alliance today – a coalition of values.

Thank you, Steve. Great to hear from you! “Alliance” is a good word. It’s the arts re-united, reconstituted. That’s the mission of the frame-maker today.