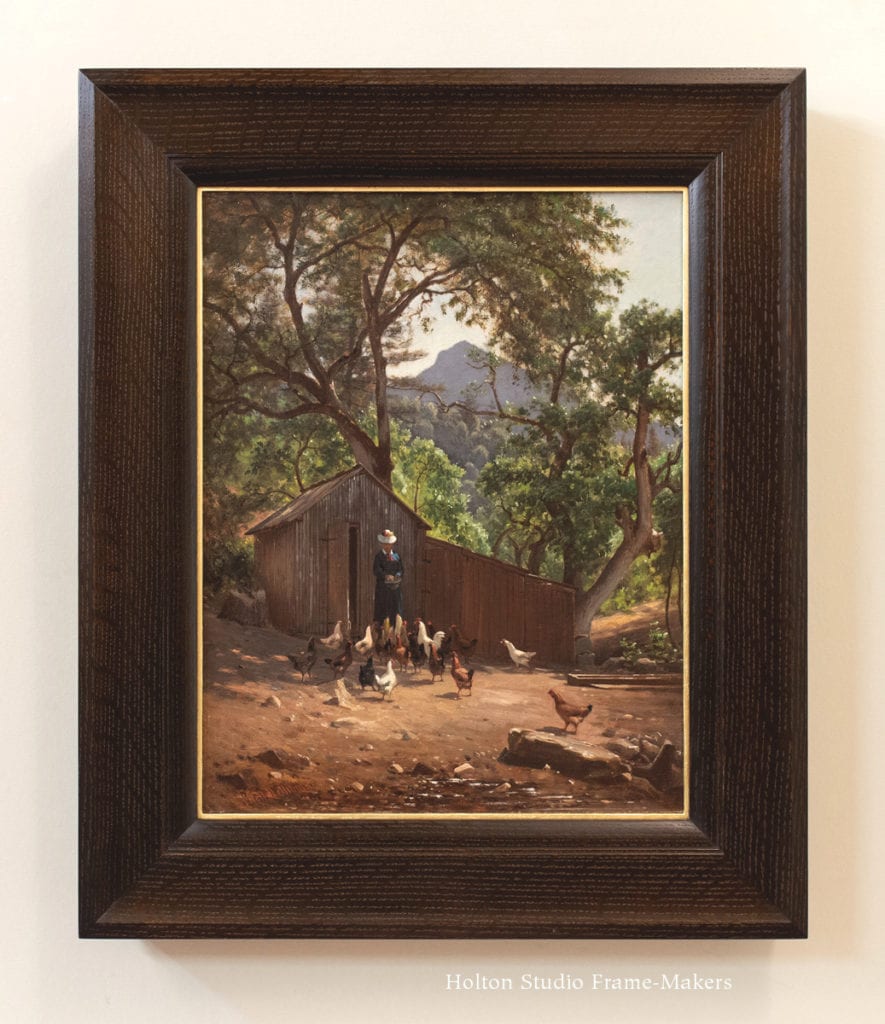

We recently re-framed this oil painting by Virgil Williams (1830-1886) of his wife Dora feeding chickens on their farm near Mt St Helena, which towers in the background. The 18″ x 14″ painting is undated but was probably painted in the 1880’s. The frame, in a 3-1/4″ wide profile, is in quartersawn white oak with Dark Medieval Oak stain. It has an 18 kt gilt slip. The idea was to suit the painting’s still mood with a simple profile, but one that would no less be a match for the refined lines and formal rendering of the painting. Note the harmony of the shed with its natural surroundings, its roof even echoing the lines of the mountain behind it. As architecture, the frame is naturally attuned to the characteristics of the shed. Its subtle elements gently lead you in to the quiet afternoon scene.

More work by Virgil Williams

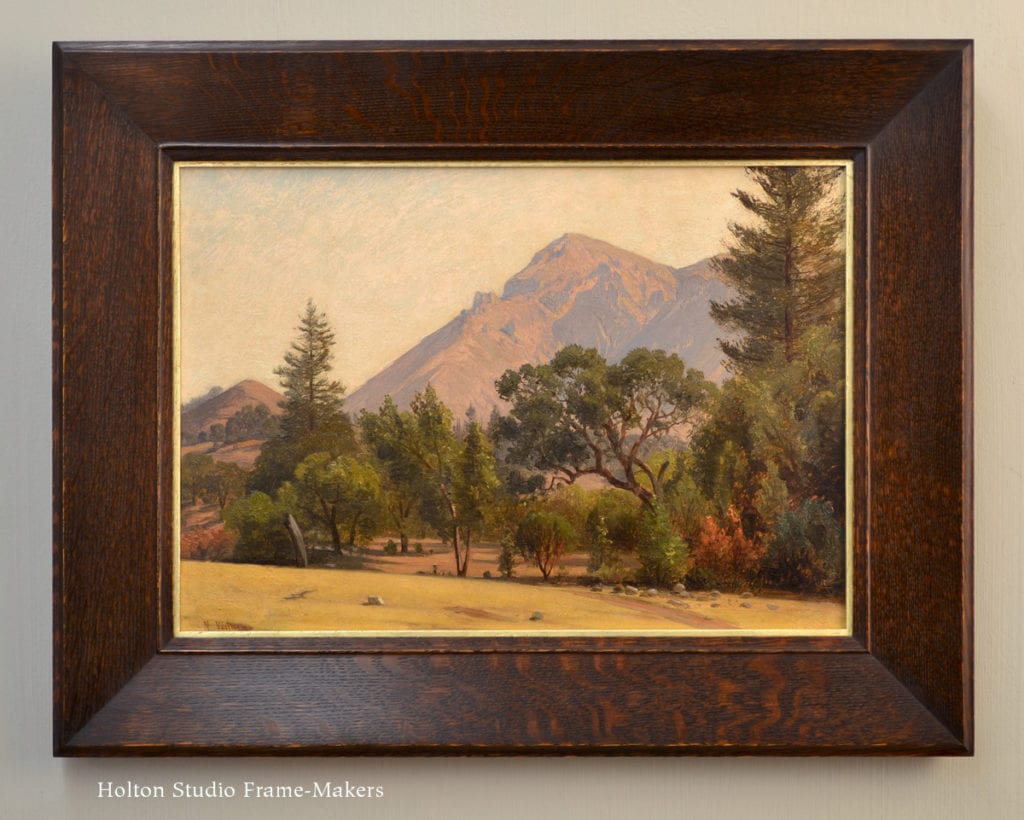

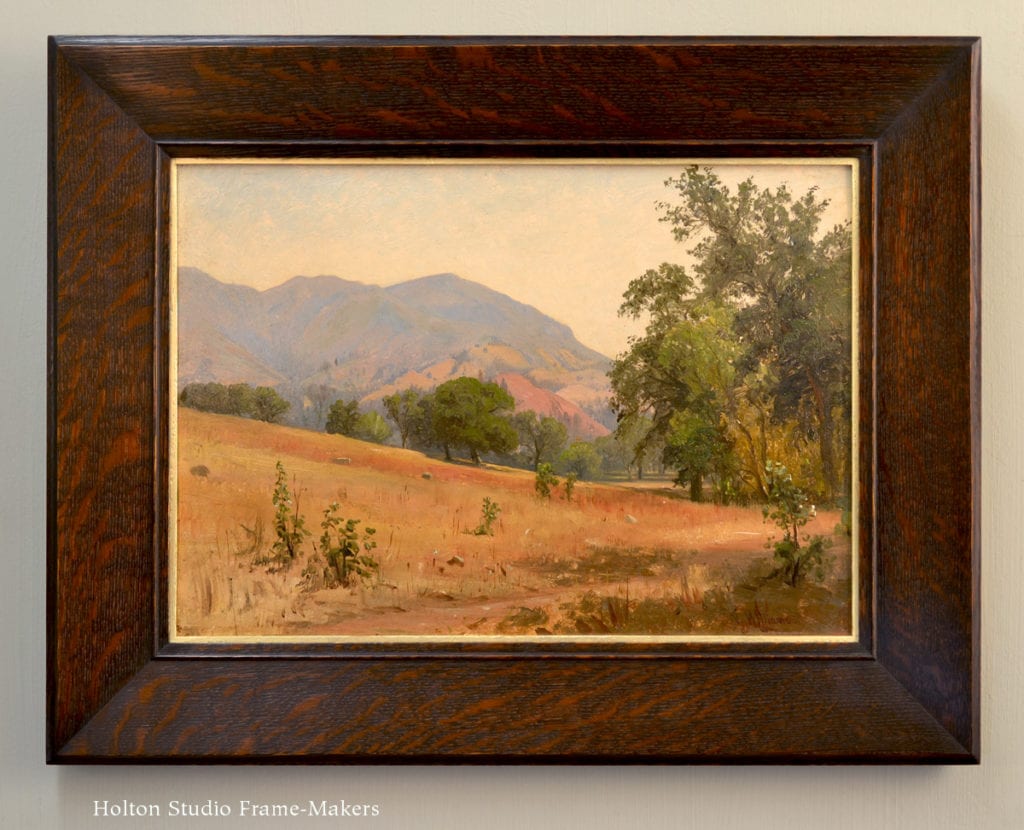

Here are two more paintings by the same artist, framed a year or so ago, both in our No. 238 at 3″ wide, in quartersawn white oak (Dark Medieval Oak stain):

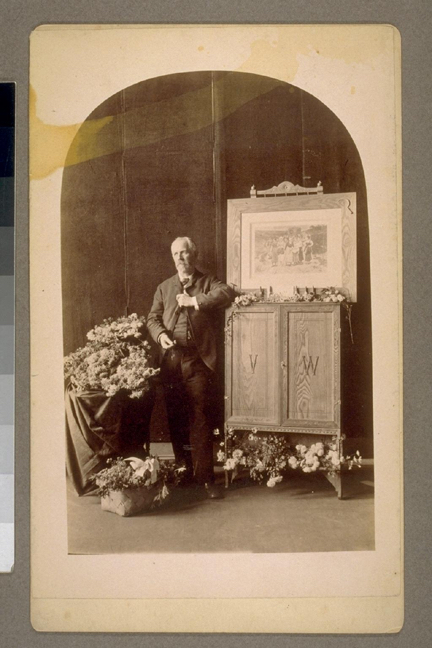

Virgil Williams

The following notes on Williams, including how he framed the entire concept of “art,” are from a 1937 WPA monograph in UC Berkeley’s Bancroft Library, on leading painters of California. It includes some particularly interesting perspective on the social place of painting—with suggestions of how its dubious uses were reflected in their physical place, their frames.

Virgil Williams came from an old New England Protestant family—a direct descendant, in fact, of Roger Williams. “In such a family and such an atmosphere,” notes the monograph, “Virgil’s desire to become an artist entailed the shattering of tradition.” Thus, before coming West in 1871 to settle in San Francisco and play a key role in fostering the City’s especially lively world of painting in those burgeoning days, he spent a decade in Rome, immersed in Italy’s Catholic and Renaissance heritage. The experience was perhaps a necessary antidote to the artist’s inherited puritan austerity and distrust of “worldly” and even idolatrous occupations like painting. In any case, once reluctantly returning to Boston, “Something in the atmosphere of the more established East seemed to pall on Williams,” writes the same biographer, “There was that in the artist which sought to express itself… Artistically, Virgil Williams had not yet found himself.” The monograph suggests that for the painter, part of the charm of California was a climate reminiscent of his “beloved Naples and Capri.” Here his work caught on and found an appreciative audience.

Virgil Williams, Teacher

But finally, it was as a teacher perhaps more than as a painter, that Williams left his mark on this state.

“In 1874, a committee from the Art Association appointed to form and carry out plans for the opening of an art school,” the monograph says. “Virgil Williams was selected and they could scarcely have made a happier choice.” The school being founded was the California School of Design—what is now the San Francisco Art Institute. Williams enjoyed soaring repute as an instructor. “A great deal should be said of Virgil Williams,” a reporter exclaimed in 1885,

the man who has made this school his life-work, and who has as an instructor no superior and probably no equal in the United States. It is impossible for an outsider, or for such professionals as have no standards of comparison to appreciate the work this man has done single-handed… He spends his entire time with his pupils, is always accessible to them, and takes a lively personal interest in them all.

Williams’s students included Arthur Mathews, Charles Hittel, JE Stuart, Mary Curtis Richardson, Matilda Lotz, Chris Jorgensen, Guy Rose, Alice Brown Chittenden, William Hubacek, and Edith White. Testimony to his influence may well be measured by the plaque that, after he died, his students had installed at the school. The plaque included the epigraph, “He shaped the dawn of Western art and prophesied its noon.”

How San Francisco’s Early Elite Framed Art

But to return to the circumstances that welcomed Virgil Williams to early San Francisco, the monograph offers some interesting perspective on the place—reflected by the literal place—of paintings in the larger setting of the time. When Williams arrived in 1871,

The City of San Francisco was just entering on the period of her greatest artistic development. Conditions that fostered this period, were peculiar. There were many wealthy men in the community, nouveau riche though they were, who took pride in patronizing the arts. This generosity attracted many artists whose names became associated with the period. These nabobs were building their palatial homes on San Francisco’s Nob Hill. True[,] many of them were prone to judge a canvas by its size and the amount of gilt paint on the frame, but they felt it added to their cultural standing to buy paintings, good or bad. As a result the whole city became unusually art conscious…

Here we have an excellent window, from the vantage point of the far different era of the Great Depression, on social and cultural concerns—status consciousness of an insecure emerging urban elite—that helps shed light on the frame choices of the era. With “cultural standing” being the point in acquiring and displaying paintings in one’s “palatial mansion,” it’s not hard to see how pictures were judged by their “size and the amount of gilt paint on the frame”; and how even images of humble sheds and chicken yards wound up in such bizarrely incongruous and ostentatious settings with no evident concern for enhancing the picture’s inherent, particular character. It’s the picture, not as particular, close and penetrating observation of life, but the picture generalized as “Art”—a thing to be shown off as a trophy, evidence of one’s social prestige.

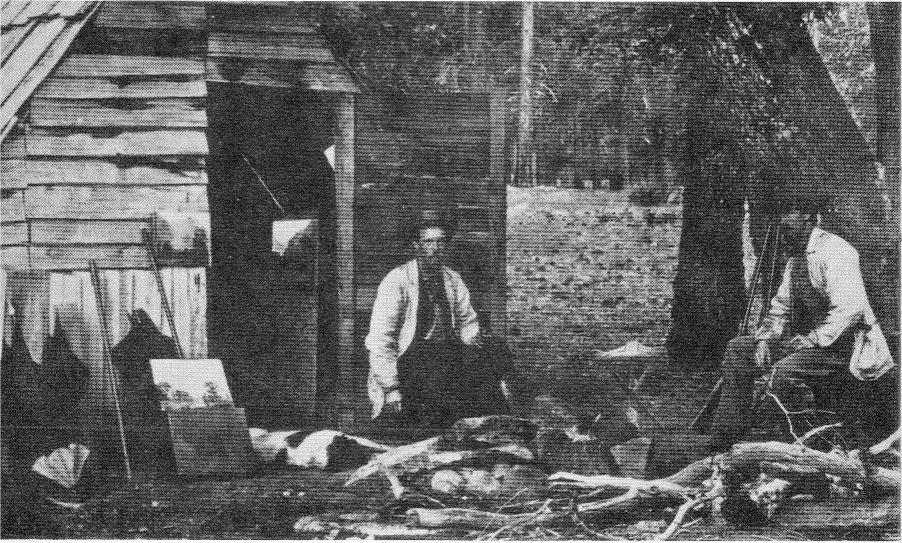

Those today who actually would like to enjoy these paintings themselves face an endless project in re-framing. Two examples may be seen below in before-and-after comparisons of other Williams paintings we re-framed. The first is another of Dora feeding the chickens, the second, one of the pieces shown above.

How Virgil Williams Framed Art

By the late nineteenth century, industrialization and its thorough disruption of the nature of human labor had obliterated the old integrated system of the arts, and along with that the original meaning of the word art. The age had witnessed the modern invention of “art,” a vague and debased social construct eluding definition. In this new regime, no one could blame even an acclaimed painting instructor for struggling with the idea, as Williams does below, in the quote I’ll end with.

In 1886, a young reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle, interrogated The City’s artists on a “definition of art.”

“What is art, Director Williams?”

“Art is long and time is fleeting,” merrily answer Virgil Williams, disengaging his attention from the arrangement of an adroit piece of mechanism designed to illustrate the principles of perspective to the pupils of the School of Design.

“Can’t you show any more respect to a subject you honor with the devotion a lifetime?”

“No one has ever defined it yet,” he said, contemplatively twirling a piece of chalk between his thumb and forefinger.“But how do you define it, Mr. Williams?

“God bless me! I don’t know. Webster gives it a purely mechanical definition, but that isn’t right. The truth of it is, there are different kinds of art, and high art is a compound quantity. I cannot define it better than to say that judgment, skill and taste all enter into it.”

“There are ever so many fashions in art,” continued Mr.Williams, waxing retrospective.

“Thirty years ago the [Pre-]Raphaelite school was the rage in England; now the impressionist and realistic contend for the possession of the field. In twenty-five years more some other style will be in vogue. I may not live to see the day, but it is sure to come. It’s all nonsense, just like the eternal wrangle over straight and curved lines. I was taught to draw with curved lines, and now it is all in vogue to draw with straight lines; but we are sure to come back to the curved lines after another generation. Of course, there are certain methods with experience has proved effective, but the manner of painting is of small consequence, compared to what is achieved. By Jove! Let a man paint with his toes or his thumbs, or stand on his head and paint if he finds it more comfortable. All the public cares of after all is what kind of a picture he makes.”

Virgil Williams’s 1880 painting of Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife, Fanny, at left. Painted during the couple’s honeymoon in Northern California. The woman on the right is Dora—not, this time, feeding chickens!

« Back to Blog

How interesting – many thanks.

Marty