“I have met in my lifetime some extremely revolutionary characters; and quite a large number of them, when I have asked, ‘Who put you onto this revolutionary line? Was it Karl Marx?’ have answered,

‘No, it was Ruskin.’” —George Bernard Shaw“The book was impossible to lay aside, once I had begun it. It gripped me… I could not get any sleep that night. I determined to change my life in accordance with the ideals of the book. ”

—Mahatma Gandhi, on reading Ruskin’s Unto This Last

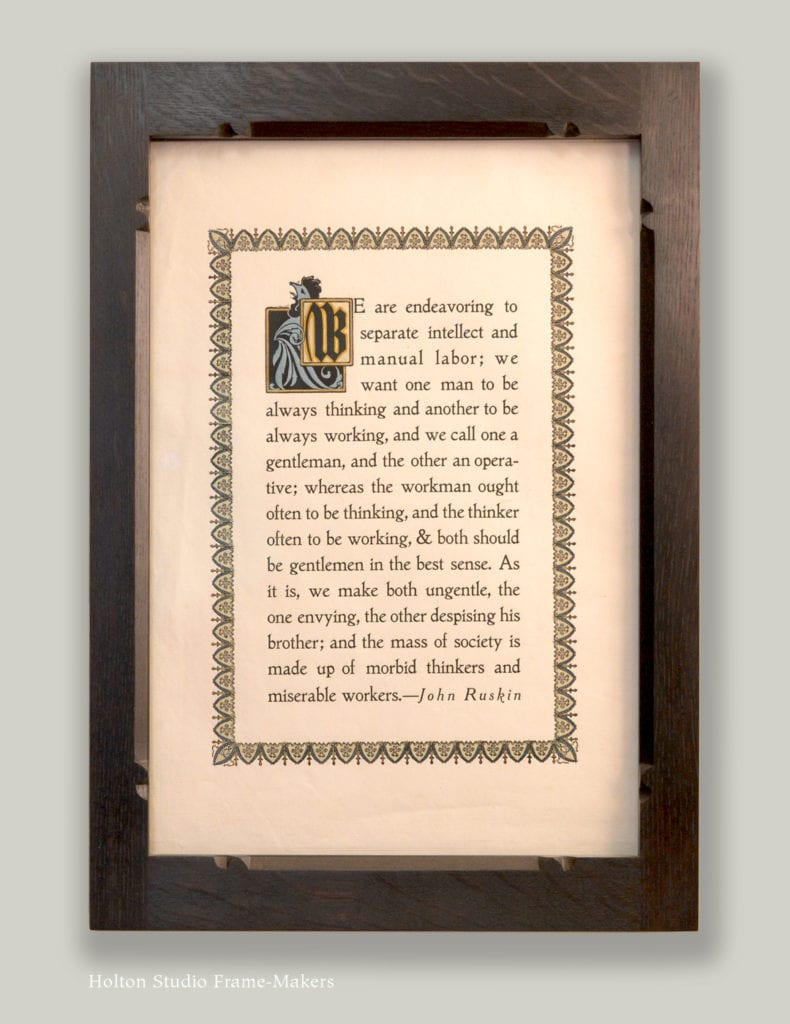

Today is John Ruskin’s 200th birthday, so to celebrate his influence and thought I’m posting this quote from Ruskin’s “The Nature of Gothic.” This antique sheet, measuring 15″ x 10″, was published by the Roycroft workshops over a century ago. It was a gift to me from Professor Jim Spates and other members of a wonderful group of Ruskin scholars I’ve come to know and with whom I put together a couple of symposia at the Hillside Club here in Berkeley. (Read Jim’s enlightening blog on Ruskin here.)  I don’t have much time to post today, but for me personally, this quote is a prime example of the great diagnosis informing and underlying all Ruskin had to say: that modern life is plagued by separation and division. Our response, then, must be to restore and reconstitute it—to join the world anew. This project must begin in our labor, which, as the “The Nature of Gothic” makes clear, should involve mending the division between head and hand which is so harmful to both individuals and society. William Morris said of that text: “To some of us when we first read it… it seemed to point out a new road on which the world should travel.”

I don’t have much time to post today, but for me personally, this quote is a prime example of the great diagnosis informing and underlying all Ruskin had to say: that modern life is plagued by separation and division. Our response, then, must be to restore and reconstitute it—to join the world anew. This project must begin in our labor, which, as the “The Nature of Gothic” makes clear, should involve mending the division between head and hand which is so harmful to both individuals and society. William Morris said of that text: “To some of us when we first read it… it seemed to point out a new road on which the world should travel.”

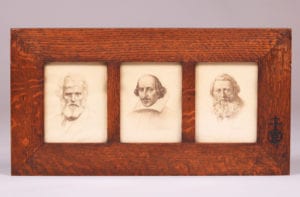

Shown below is another item to come out of the Roycroft workshops, a triptych of great thinkers with Ruskin, along with Thomas Carlyle, flanking none other than William Shakespeare. Ruskin was widely regarded as the greatest prose writer of his day. But, as the New York Times tribute pointed out this week, “Time hasn’t been kind to the reputation of John Ruskin. Two hundred years after his birth, hardly anyone today remembers Victorian England’s pre-eminent art critic and social philosopher for his books”—that is, for his wisdom and teaching. His lectures, even when held in the largest halls, drew overflow audiences. His influence on not only Victorian England but the world was profound, extensive and acknowledged—until it rapidly began to weaken and dwindle sometime after World War I. (Ruskin died in 1900.) In the age of progress and machines, Ruskin’s challenge to modernity—not so much a challenge to its achievements as to the moral and environmental costs and limits of those achievements—felt to more and more people like a restraint on freedom. He seemed a man unfit for the age—a prophet of yesteryear, not of today.

Shown below is another item to come out of the Roycroft workshops, a triptych of great thinkers with Ruskin, along with Thomas Carlyle, flanking none other than William Shakespeare. Ruskin was widely regarded as the greatest prose writer of his day. But, as the New York Times tribute pointed out this week, “Time hasn’t been kind to the reputation of John Ruskin. Two hundred years after his birth, hardly anyone today remembers Victorian England’s pre-eminent art critic and social philosopher for his books”—that is, for his wisdom and teaching. His lectures, even when held in the largest halls, drew overflow audiences. His influence on not only Victorian England but the world was profound, extensive and acknowledged—until it rapidly began to weaken and dwindle sometime after World War I. (Ruskin died in 1900.) In the age of progress and machines, Ruskin’s challenge to modernity—not so much a challenge to its achievements as to the moral and environmental costs and limits of those achievements—felt to more and more people like a restraint on freedom. He seemed a man unfit for the age—a prophet of yesteryear, not of today.

Curious then, that Ruskin’s motto was “TO-DAY,” reflecting his thorough delight in simply being alive in a world of infinite beauty, and his passionate belief in the possibility of the world’s redemption. And curious also that two of the twentieth century’s greatest leaders in the fight for social justice drew directly from Ruskin’s inspired vision. Mahatma Gandhi’s quote at the top of this post, which comes from a chapter in his autobiography titled “The Magic Spell of a Book,” goes on to say that Unto This Last, Ruskin’s powerful repudiation of laissez-faire economics, “brought about an instantaneous and practical transformation in my life… I translated it later into Gujarati, entitling it Sarvodaya (the welfare of all).” (Ruskin’s book contains what is probably his most famous quote: “There is no wealth but life.”) Martin Luther King, Jr. would draw on Ruskin’s thought via Gandhi’s work, of course, but also through the writings of the American theologian Walter Rauschenbusch, the leader of Social Gospel movement. (More on that in this blog post.)

And I haven’t even mentioned the extraordinarily prophetic “Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century,” which anticipates climate change. Just as “The Nature of Gothic” pointed all eyes on the separation of intellect and work and the harmful effect of the modern economists’ principle of division of labor—”It is not the labor that is divided, but the men”—Ruskin took the industrial age to task for turning humanity’s relationship with the earth into one of “broken harmony.” Ruskin saw the world coming apart. In his waning years he tired of writing about it and resolved to do something about it. So he founded the Guild of St George. The Guild’s namesake was not only the patron saint of Great Britain but is best known as the slayer of a dragon—the dragon being, for Ruskin, “the Lord of Decomposition.” If such views were regarded as alarmist and Cassandra-like, how many of us today would readily describe the state of the world as deeply, profoundly divided and fractured?

And I haven’t even mentioned the extraordinarily prophetic “Storm Cloud of the Nineteenth Century,” which anticipates climate change. Just as “The Nature of Gothic” pointed all eyes on the separation of intellect and work and the harmful effect of the modern economists’ principle of division of labor—”It is not the labor that is divided, but the men”—Ruskin took the industrial age to task for turning humanity’s relationship with the earth into one of “broken harmony.” Ruskin saw the world coming apart. In his waning years he tired of writing about it and resolved to do something about it. So he founded the Guild of St George. The Guild’s namesake was not only the patron saint of Great Britain but is best known as the slayer of a dragon—the dragon being, for Ruskin, “the Lord of Decomposition.” If such views were regarded as alarmist and Cassandra-like, how many of us today would readily describe the state of the world as deeply, profoundly divided and fractured?

In the New York Times piece, Jim Spates, who gave me the Roycroft piece featured above, is quoted as saying that Ruskin “holds our feet to the moral fire. He makes us disconcerted. My belief is Ruskin is a spot-on critique (sic) of modern America, and is relevant now as he was then.”

Spot-on too is the article’s concluding line: “Maybe we should go back to him: He saw it coming.”

I, for one, regard Ruskin as immortal as any of us can hope to be, if for no other reason than one that Ruskin left us for believing in the enduring effect of every life that’s well lived:

“Life, when it is real, is not evanescent, is not slight, does not vanish away. Every noble life leaves the fibre of it interwoven forever in the work of the world; by so much, evermore, the strength of the human race has gained; more stubborn in the root, higher towards heaven in the branch.”

If his reputation is that of a man who refused to join the modern world, his life’s work was nonetheless to join the world. And he is, thankfully, and despite our broken world, joined to us still—”interwoven in the work of the world.” If we are going to mend our broken world, to slay the Lord of Decomposition, we need Ruskin’s wisdom to-day as much as ever, reminding us that

The system of the world is entirely one; small things and great are alike part of one mighty whole.

Happy Birthday, John Ruskin.

To learn more about Ruskin, the Wikipedia entry is very good. For an introduction to his writing, you can’t do better than Clive Wilmer’s anthology, John Ruskin: Unto This Last and Other Writings (Penguin) and John Rosenberg’s The Genius of Ruskin (out of print, but available used).

« Back to Blog