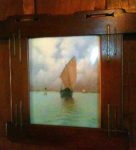

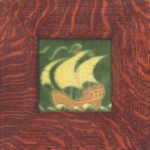

Here’s an exemplary Arts and Crafts tile we just framed. It’s over a century old, made by the outstanding Cincinnati tile maker, Rookwood (founded in 1880 and still active!). If you’re at all familiar with the Arts and Crafts Movement, you’ve probably noticed the prevalence of the motif of galleons, clippers, man-of-wars, schooners and other ships. (A bunch of examples are at the bottom of this post.) Why are such vessels so iconic? What was their significance in the minds of Arts and Crafts artisans? Was it nothing more than an example of the nostalgia and romanticism of a fundamentally backward-looking movement? Simply a trivial fashion thing? The answers take some digging, but lead us to childhood wonder, and to the heart of Arts and Crafts ideals—and very much to the spirit of this special season.

British Maritime History

It is oddly difficult to find a simple answer to why ships were so important to the Arts and Crafts Movement. None of the better known leaders of the movement, so far as I’ve been able to find, come out and state the reason. Certainly the British origins of the movement, and romantic memories of that nation’s great maritime history, typified by “Rule, Britannia,” have a lot to do with it. Ships were integral to the identity of a nation both surrounded by sea and with a history of far-flung empire. The movement was largely based in London, where the Thames was the heart of life, including commercial traffic carried out in boats.

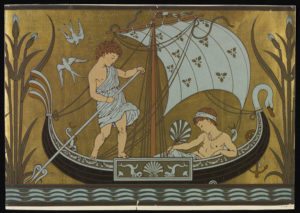

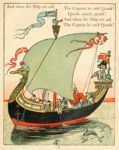

Key figures in the movement grew up around harbors and developed a child’s wonder in ships and seamanship, such interests and imagery thus being planted deep in their psyches. One example is Walter Crane, a brilliant pictorial artist and designer and the first president of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society. In his autobiography, Crane recalled of his childhood,

Living…near the harbour [of Torquay, Devon], it was natural, in the constant sight of ships and sailors and the life of the quays, to become interested in nautical matters and all that belonged to the sea, and we prided ourselves on correctly distinguishing the different rigs of the various types of vessels… It was immense fun, when, finding a good-natured skipper, we children were allowed to ramble over a ship as it lay moored to the pier or quay, especially if it were a large barque or “three-master.”

Out of such beloved material of the imagination, works of art naturally grew, and Crane would produce a substantial body of children’s book illustrations and other pictorial and decorative work on the theme of ships. (At right and below.)

Turner

Another key figure for reformers was JMW Turner (1775-1851), one of the greatest painters of ships who ever lived. His 1838 canvas The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her last berth to be broken up, below, has claimed the hearts of the nation to this day; in 2005 Brits voted it their favorite painting. There’s no denying the nostalgic appeal here. John Ruskin called this work Turner’s “pensive farewell to the old Temeraire, and with it, to that order of things.”

Turner’s importance to the Arts and Crafts Movement is often overlooked by those who narrowly associate the movement with “brown furniture and green pots.” But he was the primary subject of and inspiration for Ruskin, the father of the movement, in his five volume Modern Painters, which contains several famous passages on Turner’s depictions of and relationship to sailing vessels. The writer’s description of The Slave Ship (read a previous post about that painting here) became a favorite example of Ruskin’s celebrated ornate early prose style. “The Two Boyhoods,” one of the best known chapters in Modern Painters, compared Italian Renaissance painter Giorgone’s early days in indescribably beautiful 15th century Venice—”a golden city paved with emerald”—to Turner’s poor childhood in the muddy and blackened London slum of Covent Garden. Condemned to such a blighted place without a square inch of unspoiled nature, how could Turner’s eyes ever have found anything like the beauty to inspire him to become the masterful painter of nature that he did? Ruskin surmised that it was in the thick of masts populating the nearby Thames that the painter was able to transcend the ugliness of the city. “That mysterious forest below London Bridge—”

Turner’s importance to the Arts and Crafts Movement is often overlooked by those who narrowly associate the movement with “brown furniture and green pots.” But he was the primary subject of and inspiration for Ruskin, the father of the movement, in his five volume Modern Painters, which contains several famous passages on Turner’s depictions of and relationship to sailing vessels. The writer’s description of The Slave Ship (read a previous post about that painting here) became a favorite example of Ruskin’s celebrated ornate early prose style. “The Two Boyhoods,” one of the best known chapters in Modern Painters, compared Italian Renaissance painter Giorgone’s early days in indescribably beautiful 15th century Venice—”a golden city paved with emerald”—to Turner’s poor childhood in the muddy and blackened London slum of Covent Garden. Condemned to such a blighted place without a square inch of unspoiled nature, how could Turner’s eyes ever have found anything like the beauty to inspire him to become the masterful painter of nature that he did? Ruskin surmised that it was in the thick of masts populating the nearby Thames that the painter was able to transcend the ugliness of the city. “That mysterious forest below London Bridge—”

better for the boy than wood of pine, or grove of myrtle. How he must have tormented the watermen, beseeching them to let him crouch anywhere in the bows, quiet as a log, so only that he might get floated down there among the ships, and round and round the ships, and with the ships, and by the ships, and under the ships, staring and clambering; — these the only quite beautiful things he can see in all the world, except the sky; but these, when the sun is on their sails, filling or falling, endlessly disordered by sway of tide and stress of anchorage, beautiful unspeakably; which ships also are inhabited by glorious creatures — red-faced sailors, with pipes, appearing over the gunwales, true knights, over their castle parapets — the most angelic beings in the whole compass of London world.

The connection Ruskin makes here between the beauty of ships and the hard physical labor of the “glorious creatures” who build, maintain and operate them is another key concern at the heart of Arts and Crafts ideals: work, and the life and conditions of the laborer. (A prime example of this is the detail at left of Turner’s painting of the scene of Admiral Nelson’s death on the deck of the Victory.) Turner, said Ruskin, would become a painter not only of “the strength of nature, there was no beauty elsewhere than in that; he must paint also the labour and sorrow and passing away of men…”

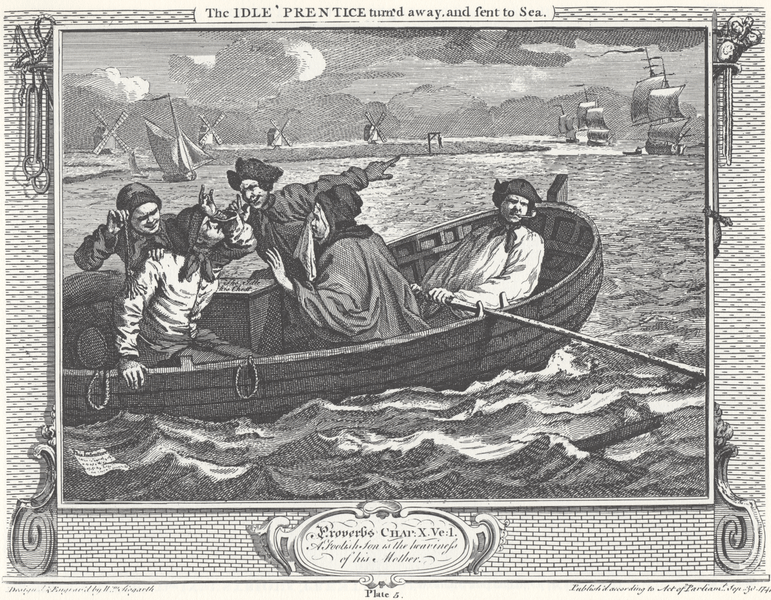

Hogarth

Modern Painters was an enormous inspiration to reformers—especially to the Pre-Raphaelites. But an even earlier book must also be acknowledged for its influence, and it’s one in which the image of the ship is key.

In 1858, after the PreRaphaelite Brotherhood was dissolved, former members and sympathizers of the group, including William Morris, formed The Hogarth Club to sustain the Brotherhood’s opposition to the Royal Academy. Nineteenth century reformers admired the eighteenth century painter William Hogarth for having stubbornly stood up for the old, more unified system of the arts as it was being increasingly threatened by modern social conditions. They praised Hogarth not only for his paintings but also for his book “Analysis of Beauty,” written in answer to the increasingly dominant academic fashions of the eighteenth century. Its appeal to painters to reject academic rules and conventions and instead “to see with our own eyes” articulated a century before Modern Painters this and other guiding principles of design reform.

But what did Hogarth’s book have to do with ships? “Analysis of Beauty” identified six principles of beauty, the first of which was “Fitness.” The chapter opened,

Fitness of the parts to the design for which every individual thing is formed, either by art or nature, is first to be considered, as it is of the greatest consequence to the beauty of the whole.

As part of his illustration, Hogarth explained that

[I]n ship-building the dimensions of every part are confined and regulated by fitness for sailing. When a vessel sails well, the sailors always call her a beauty; the two ideas have such a connexion!

Advocates of the reform of not only painting but the decorative arts as well, which in the Victorian era had become embarrassingly debased from fundamental design concerns like utility and materials, found Hogarth’s point about fitness powerfully compelling: the word “decorative,” related to “decorum,” is very much rooted in the idea of fitness—propriety, suitability, seemliness. Clearly restoring “connexion” between beauty and function informed the movement’s ideal of “the beautiful necessity.” A ship is a work of art no less than a painting is. Its service to life and embodiment of vigorous human labor doesn’t make it less expressive of our humanity; in many ways it’s more so.

And the idea of a well-made and well-run ship reflects the ideal of the cooperation and combination of multiple trades in not only shipbuilding but architecture—a principle key to reformers’ admiration for Gothic architecture and thus not only characterizing but truly defining the aims of Arts and Crafts architects. In reference to the example at hand, the Rookwood tile we just framed (a great period Rookwood tile framing example is shown at right), this ideal embodied by ships thus shines an ennobling light on the work of the frame-maker, an artisan whose ability as a designer must be judged first of all by the standard of fitness and suitability of his or her work to the work of another artist—a painter or pictorial artist (or, in this case tile maker). Subordinate to and distinct from the picture (or tile) though the frame is, the full appreciation of the picture depends on its presentation and the honor bestowed on it by a frame design enhancing and being well adapted to the tile’s design and character.

I’m probably in danger of letting this example trivialize a hugely important aspect of our theme. The ideal of combined and mutually enhancing labor and arts was a key part of the great social ideals of a movement ultimately concerned with the reconstitution of society on principles not of competition and division but cooperation and harmony.

Unity

Unity

In the Rookwood tile we just framed, the ultimate ideal expressed by the Arts and Crafts ship motif is suggested by the placing of the ship in a circle. Black Elk said that “Everything the Power of the World does is done in a circle.”* Hogarth’s statement of a principle “for which every individual thing is formed, either by art or nature” was audaciously both all-encompassing and all-unifying, reflecting a powerful need to restore the arts to timeless and immutable, universal laws ultimately grounded on the universal observation of a great oneness. Emblematic of harmony of parts and “the beauty of the whole,” ships represented the ideal of unity that was at the heart of the Arts and Crafts Movement and made it so compelling. In fact, the sea itself could be said to stand for this ideal; Ruskin wrote of the “wild, various, fantastic, tameless unity of the sea.” Ships on the sea, then—like those “pillars of the earth,” Gothic churches—would clearly be associated with a primary aspect of this larger ideal: the unity of human creation with nature’s—the unity, that is, of all things. “The system of the world,” Ruskin wrote, “is entirely one; small things and great are alike part of one mighty whole.”

And the laws of all things formed “either by art or nature” were the same. According to Ruskin, “A pure or holy state of anything…is that in which all its parts are helpful or consistent,”—as they are on a well-built, well-manned ship. Such ships, “composed of many elements in an entirely helpful state,” were emblematic of “the Law of ‘Help'”— “the highest and first law of the universe—and the other name of life.”

“The Fellowship of the World”

So a little bit of research turns up the reason why the ship motif is so common in Arts and Crafts objects—and it was no trivial matter of fashion, but was symbolic of matters of enormous meaning, power and consequence. While ship motifs might seem at first merely romantic and nostalgic, the ideals they represented to members of the movement were not backward-looking but timeless. As an internationally renowned designer and illustrator, in the 1890’s Crane sailed to America, and his work here indicated a very forward-looking reason for reformers’ fascination with ships: the appeal of sea vessels in their work of connecting the world’s continents, nations and peoples. Crane described in his autobiography one wall paper design which includes ships, as well as the role of such vessels in a momentous gathering of global nations.

While in New York I completed a rather elaborate design for a wallpaper with an extensive frieze intended as a special exhibit at the Chicago World’s Fair the next year. The filling bore Columbus’s ship, the Stars and Stripes, and other emblems in a sort of diaper, and the frieze motive was a line of beaked ships with bulging sails, in each of which stood a female figure, typifying the parts of the earth welcomed by America, also standing in her ship labelled Chicago, who joins their hands.

For words to capture this joining, unifying spirit—expressive of ideals in no way retrograde or trivial but timeless—who better to turn to than Ruskin and his preface to a book of Turner’s maritime etchings, Harbours of England? Though often overcome with despair for his nation and the world, in those harbors Ruskin could still find something to rekindle his boyhood imagination and fill him with profound hope:

Of all things, living or lifeless, upon this strange earth, there is but one which…I still regard with unmitigated amazement…and never pass without the renewed wonder of childhood,…and that is the bow of a Boat…The nails that fasten together the planks of the boat’s bow are the rivets of the fellowship of the world. Their iron does more than draw lightning out of heaven, it leads love round the earth.

Here’s to the wonder of ships—not only for children but for us all—and to peace, goodwill and love round the earth.

Happy holidays!

Read “The Sailing Ship as an Arts and Crafts Motif” on the blog, “Colonel Unthank’s Norwich.”

Walter Crane’s ships—

- Crane illustration for William Morris’s “The Glittering Plain”

- “The Fairy Ship”

- End paper for “The Fairy Ship”

- “The Story of Greece”

- “I Saw Three Ships”

- “Faithful John”

Turner’s ships—

- Battle of Trafalgar, 1822

- The Battle of Trafalgar, as Seen from the Mizen Starboard Shrouds of the Victory, 1806-8

- Ulysses Deriding Polyphemus

- On the Tyne

- Venice: The Dogana and San Giorgio Maggiore

- Venice—The Rialto, 1821-3

- Whitby, 1826, from Harbours of England

- Ramsgate, from Harbours of England

Other Arts and Crafts tiles with ships—

- William DeMorgan

- William DeMorgan

- William DeMorgan

- William DeMorgan

- Rookwood tile by Carl Schmitt in Gamble House (Hall Brothers frame)

- Rookwood tile in original oak frame

- Rookwood tile in original oak frame

- Rookwood tile in original oak frame

- Rookwood tile

- Rookwood

- CFA Voysey, Pilkington Galley tile

Other Arts and Crafts items with ships—

- Edward Burne-Jones stained glass

- Greene and Greene firescreen detail (from Thorsen House)

- John Pearson copper charger, 1904

- CR Ashbee leather panels

- Etching by Frank Brangwyn, “Last of the HMS Britannia”

- CFA Voysey

* “Everything the Power of the World does is done in a circle. The sky is round, and I have heard that the earth is round like a ball, and so are all the stars. The wind, in its greatest power, whirls. Birds make their nests in circles, for theirs is the same religion as ours. The sun comes forth and goes down again in a circle. The moon does the same, and both are round. Even the seasons form a great circle in their changing, and always come back again to where they were. The life of a man is a circle from childhood to childhood, and so it is in everything where power moves. Our tepees were round like the nests of birds and these were always set in a circle, the nation’s hoop, a nest of many nests, where the Great Spirit meant for us to hatch our children.” —Black Elk, the Lakota Indian wise man and leader

This quote was included in a wonderful recent post, also on the matter of the unity of all things, by Doug Stowe, on Wisdom of the Hands, here.

« Back to Blog