In preparation for tonight’s event with portrait photographer Nan Phelps, I’m thinking more deeply than usual about portrait photography and how it’s framed. As I touched on in my last post, the essential problem of framing black and white portrait photography can be attributed to the very nature of the medium and its origins: unlike other pictorial media, photographs weren’t made to hang on our walls. Born in an age of massive commercial and social mobilization and expansion, photography was created in service to that age and in response to the demands of increasingly impermanent, transient, and simply unfamiliar social conditions—many of which were unprecedented in scale and scope. Naturally, the place of photographs in a world suddenly much more mobile and transient was likewise impermanent and portable.

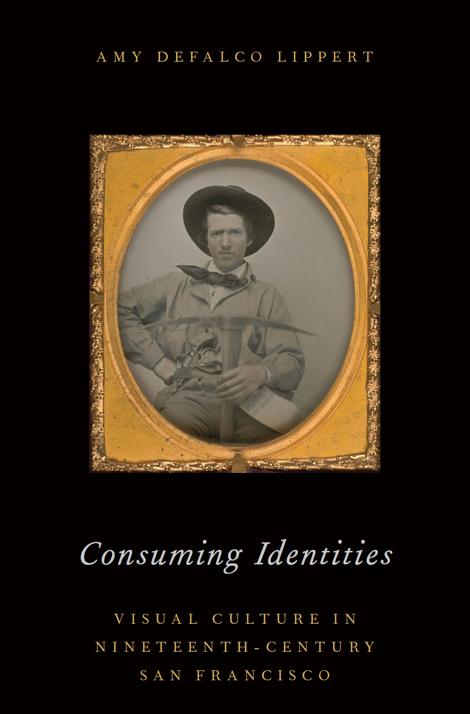

Most of what I’m learning about this I’ve gleaned from a wonderful recent book, Consuming Identities: Visual Culture in Nineteenth Century San Francisco, by Amy DeFalco Lippert, a historian at the University of Chicago. San Francisco in the gold rush years—the so-called “instant city”—provides an especially strong example of the use and power of the new technologies of pictorial reproduction.

Most of what I’m learning about this I’ve gleaned from a wonderful recent book, Consuming Identities: Visual Culture in Nineteenth Century San Francisco, by Amy DeFalco Lippert, a historian at the University of Chicago. San Francisco in the gold rush years—the so-called “instant city”—provides an especially strong example of the use and power of the new technologies of pictorial reproduction.

Photography, of course, originated in the midst of the industrial revolution. But while most of us understand and appreciate the impact and revolutionary effects of industrialization and its many social effects, rarely do we appreciate the relation of that massive historical phenomenon to photography or to the drastically altered role of pictures generally. Chiefly this impact was through the the technology of reproduction, but closely associated with that—in fact largely dependent on it—and no less important, was the invention of photography. And a third massive contributing factor of industrialization must be appreciated as well: the breakthroughs in communication and transportation that not only aided broad distribution of photographs but perhaps more importantly, the things people used those pictures for—the needs they satisfied.

The industrial revolution, in short, was also a pictorial revolution.

As it happens, and somewhat surprisingly, a key city in this revolution and the development of photography was the metropolis right across the Bay from us, which astonishingly quickly came to life in those explosive years of the mid-nineteenth century.

DeFalco Lippert writes,

From its inception, photography provided Americans with affordable access to unprecedentedly detailed renderings of the familiar and the unfamiliar: pictures of themselves, of loved ones and strangers, as well as their own landscapes and views of the world beyond the places they knew and traversed. By the mid-nineteenth century, photographs became mechanically reproducible via new image technology. Commodified images could be conveyed much more efficiently than ever before over longer distances, thanks to simultaneous improvements in the national postal system, and developments in transportation and communication infrastructures. In other words, images became much more accessible to ordinary people at the same time that they seemed more lifelike and realistic. At just this moment, the gold rush prompted a long-term and long-distance separation of friends and loved ones that ensured San Francisco a critical but heretofore overlooked role in the history of the visual medium.

…The gold rush metropolis embodied most of the century’s pivotal transformations, often in extreme forms: the separation, isolation, and individualism of the industrial era gave rise to a society in which the distinction between lived and virtual reality became as tantalizing as it was increasingly difficult to locate or discern.

Apropos tonight’s event, the author points out that “Human portraits were by far the most popular form of photography, and they enjoyed a particularly avid reception in the United States.” And in gold rush San Francisco the “extreme forms” of the century’s social changes “infused [these portraits] with heightened levels of significance because they served as irreplaceable sources of virtual intimacy for a dislocated and anonymous urban populace.”

In regards to framing photographs for our walls, recognizing the origins of photography in a society characterized by “dislocation” is key. The uniquely impermanent and transitory qualities of photography, seemingly rooted in its very genesis, go a long way toward explaining the problem, mentioned in my last post, of giving photographs the same presence in a room that other pictures enjoy; as well as the conventional approach to framing photographs—in wide white mats and narrow-as-possible frames—that seems to ignore or even reject any connection to architecture, to our walls. But if the medium is of a piece with and reflective of an age of “separation, isolation, and individualism,” we can, paradoxically, also appreciate the tremendous power of photography as a remedy and solution to precisely those problems—its power to connect people to distant events and places that were miraculously becoming much more near, as well as to home, to loved ones. If the age was pulling people apart, photography offered a means to keep them close, make their place permanent in homes and hearts.

In regards to framing photographs for our walls, recognizing the origins of photography in a society characterized by “dislocation” is key. The uniquely impermanent and transitory qualities of photography, seemingly rooted in its very genesis, go a long way toward explaining the problem, mentioned in my last post, of giving photographs the same presence in a room that other pictures enjoy; as well as the conventional approach to framing photographs—in wide white mats and narrow-as-possible frames—that seems to ignore or even reject any connection to architecture, to our walls. But if the medium is of a piece with and reflective of an age of “separation, isolation, and individualism,” we can, paradoxically, also appreciate the tremendous power of photography as a remedy and solution to precisely those problems—its power to connect people to distant events and places that were miraculously becoming much more near, as well as to home, to loved ones. If the age was pulling people apart, photography offered a means to keep them close, make their place permanent in homes and hearts.

To that end, one early problem with photography was that photos, as objects, were impermanent and given to deterioration. The technology of papers and inks, however, would eventually give them the longevity of other pictorial media. In any case, people were in no way deterred from trying to make them as much a part of their walls and homes as other pictures were—giving them the architectural place that is the goal of the frame-maker. And in fact, around the turn of the twentieth century a new fashion in framing, one much better suited to wall display, would develop. Still, somehow that too, expressive as it was of the kind of permanent architectural place the frame-maker has historically offered, was eventually overcome by an age of that increasingly valued impermanence and disruption, leaving us today with the task of searching through a fairly short historical tradition for an understanding of how to effectively frame photographs for the home.

That, in a nutshell, is the problem explored in our little exhibit, featuring Nan Phelps’s beautiful work, of “Black and White Portrait Photographs and How to Frame Them.”

The event’s at 7:00 tonight. I hope you’ll join us!

« Back to Blog

So sorry I can’t make it. I would love to see this. Have great success!

Lee