This Christmas comes at a time of deep division and discord, not only in America but across the world. And while the electoral campaign has been the most obvious example of extraordinary acrimony, our troubles are not solely political. Wendell Berry observes that “…our country is not being destroyed by bad politics, it is being destroyed by a bad way of life. Bad politics is merely another result.”

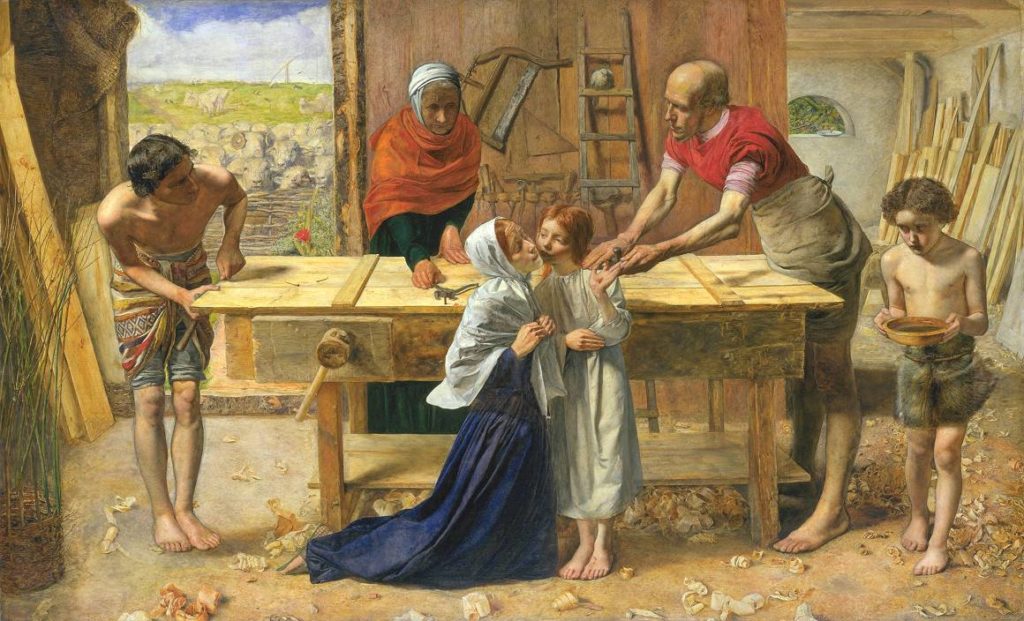

Christ in the House of His Parents (‘The Carpenter’s Shop’) 1849-50 Sir John Everett Millais, Bt 1829-1896

I post this painting today, Christmas Eve, fully conscious of the common and frequent abuse of particular faith traditions to bludgeon and divide people. But in its depiction lies a plea and a protest against precisely that abuse of religion, and against all systems of faith and ideology that mask our common humanity and breed instead hatred.

The universality I’m talking about is suggested by a remarkable observation by the great Anglo-Indian philosopher and art historian, Ananda Coomeraswamy:

“Our study of the history of architecture will make it clear that ‘harmony’ was first of all a carpenter’s word meaning ‘joinery,’ and that it was inevitable, equally in the Greek and the Indian traditions that the Father and the Son should have been ‘carpenters,’ and show that this must have been a doctrine of Neolithic, or rather ‘Hylic,’ antiquity.” —”Why Exhibit Works of Art?”, 1943

In 1850, just after the PreRaphaelite Brotherhood was founded, one of its members, John Everett Millais, displayed this painting, “Christ in the House of His Parents,” at the Royal Academy. Critics hated it, calling it “a nameless atrocity” and “plainly revolting.” John Ruskin much later recalled “Mr. [William] Dyce, R.A…. dragged me, literally, up to the Millais picture of ‘The Carpenter Shop’, which I had passed disdainfully, and forced me to look for its merits.” And Ruskin, unlike the others, indeed found its merits, and in fact soon became the PreRaphaelites’s most forceful and influential advocate.

Furthermore, in light of matters that Ruskin came to feel most passionately about, this painting has an exceptionally significant place. His almost humorous tussle with Mr Dyce might in fact be placed at the beginning of a personal story of profound crises of religious faith that plagued Ruskin for decades. It’s a story that begins in the narrow sectarianism of his early Protestant evangelicalism, through an experience of “unconversion” into a broad “religion of humanity” before returning to a Christianity he defined as small-“c” catholic.

But what draws me to this picture and its story has little to do with the story of Ruskin or history of the nineteenth century. It has to do with this deeply troubling and dark moment that our nation and world are in today. The great sense that the PreRaphaelites and Ruskin shared that civilization had lost its moral and spiritual bearings, had come off its foundations, become debased, speaks profoundly to our own time. For all our advances in technology, the same problems torment us—and are, in fact, exacerbated by our advanced technology. Because what we are seeing is a range of crises on many fronts but that all connect. They connect through the central matter directly at the heart of how we treat each other and how we sustain life. It’s the thing Millais depicted about Christ that was not, on the respectable walls of the Royal Academy, to be depicted, and the thing that the critics found so appalling: The Holy Family at work. In his PreRaphaelite insistence on truth, Millais determined we would see Christ’s family as described by the Bible—as humble working people. This great matter of work Ruskin soon took up as the central question—“the craftsman’s question”—of his teaching and of his age. And it’s a question—maybe the question if we fully comprehend all its implications—at the root of our own troubles.

So what I want to offer my readers on Christmas Eve is, besides this painting, the words of three wise men—Coomeraswamy, Ruskin and Berry—who address plainly and beautifully one of the very greatest and most urgent problems of our time. The last quote below comes from Ruskin’s 1868 lecture, “The Mystery of Life and Its Arts,” which stands like a bookend to the discovery of Millais’s painting and expresses as fully as possible Ruskin’s great revelation as to what true religion is. (I’ve left in Victorian gender prejudices, hoping readers will see through them to the more essential points about hand work.)

And it’s a message that ends in hope—hope in the knowledge of the extraordinary “vital powers” we possess in our own hands.

“[T]here is a true Church wherever one hand meets another helpfully, and that is the only holy or Mother Church which ever was, or ever shall be.”—John Ruskin, “Of Kings’ Treasuries”

“We have made it our overriding ambition to escape work, and as a consequence have debased work until it is only fit to escape from. We have debased the products of work and have been in turn debased by them…

“But is work something that we have a right to escape? And can we escape it with impunity?… All the ancient wisdom that has come down to us counsels otherwise. It tells us that work is necessary to us, as much a part of our condition as mortality; that good work is our salvation and our joy; that shoddy or dishonest or self-serving work is our curse and our doom. We have tried to escape the sweat and sorrow promised in Genesis—only to find that, in order to do so, we must forswear love and excellence, health and joy.”—Wendell Berry, “The Unsettling of America” (1977)

“The greatest of all the mysteries of life, and the most terrible, is the corruption of even the sincerest religion, which is not daily founded on rational, effective, humble, and helpful action. Helpful action, observe! for there is just one law, which obeyed, keeps all religions pure—forgotten, makes them all false. Whenever in any religious faith, dark or bright, we allow our minds to dwell upon the points in which we differ from other people, we are wrong, and in the devil’s power. That is the essence of the Pharisee’s thanksgiving—”Lord, I thank thee that I am not as other men are.” At every moment of our lives we should be trying to find out, not in what we differ with other people, but in what we agree with them; and the moment we find we can agree as to anything that should be done, kind or good, (and who but fools couldn’t?) then do it; push at it together; you can’t quarrel in a side-by-side push; but the moment that even the best men stop pushing, and begin talking, they mistake their pugnacity for piety, and it’s all over. I will not speak of the crimes which in past times have been committed in the name of Christ, nor of the follies which are at this hour held to be consistent with obedience to Him; but I will speak of the morbid corruption and waste of vital power in religious sentiment, by which the pure strength of that which should be the guiding soul of every nation, the splendour of its youthful manhood, and spotless light of its maidenhood, is averted or cast away. You may see continually girls who have never been taught to do a single useful thing thoroughly; who cannot sew, who cannot cook, who cannot cast an account, nor prepare a medicine, whose whole life has been passed either in play or in pride; you will find girls like these, when they are earnest-hearted, cast all their innate passion of religious spirit, which was meant by God to support them through the irksomeness of daily toil, into grievous and vain meditation over the meaning of the great Book, of which no syllable was ever yet to be understood but through a deed; all the instinctive wisdom and mercy of their womanhood made vain, and the glory of their pure consciences warped into fruitless agony concerning questions which the laws of common serviceable life would have either solved for them in an instant, or kept out of their way. Give such a girl any true work that will make her active in the dawn, and weary at night, with the consciousness that her fellow-creatures have indeed been the better for her day, and the powerless sorrow of her enthusiasm will transform itself into a majesty of radiant and beneficent peace.

“So with our youths. We once taught them to make Latin verses, and called them educated; now we teach them to leap and to row, to hit a ball with a bat, and call them educated. Can they plough, can they sow, can they plant at the right time, or build with a steady hand? Is it the effort of their lives to be chaste, knightly, faithful, holy in thought, lovely in word and deed? Indeed it is, with some, nay with many, and the strength of England is in them, and the hope; but we have to turn their courage from the toil of war to the toil of mercy; and their intellect from dispute of words to discernment of things; and their knighthood from the errantry of adventure to the state and fidelity of a kingly power. And then, indeed, shall abide, for them, and for us an incorruptible felicity, and an infallible religion; shall abide for us Faith, no more to be assailed by temptation, no more to be defended by wrath and by fear;—shall abide with us Hope, no more to be quenched by the years that overwhelm, or made ashamed by the shadows that betray;— shall abide for us, and with us, the greatest of these; the abiding will, the abiding name, of our Father. For the greatest of these, is Charity.”” —John Ruskin, “The Mystery of Life and Its Arts,” (1868)

May your holidays be full of light and harmony and hand craft.

« Back to Blog