I’ve just put up the web page for our current show, “Beloved California: Sixteen Painters With a Passion for Place.” Shots of the opening are at the bottom of the page. As you can see, the event was a great success, with a big, enthusiastic turnout, and beautiful live cello music (thank you Gael Alcock!). Also a rousing round of “Happy Birthday” sung to Paul Kratter! Visit the show’s page, here.

Below is the longer version of the essay I wrote to post in the gallery. Some highlights from the show are included. This piece of writing doubles as a bit of a manifesto for the gallery, which seems to be coming into its own now in our bigger and better location in Berkeley; and, we hope, as a place to cultivate something I regard as of the highest importance.

Beloved California: Sixteen Painters With a Passion for Place

A Word About Where We Are

“Beloved California” is the work of an under-appreciated but crucially important part of the culture of Northern California—its vibrant and vital community of landscape painters.

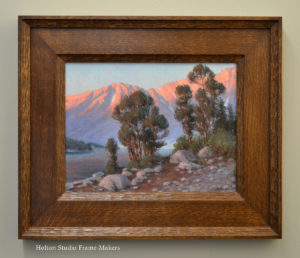

Sharon Calahan, “Sierra Glow”

I’d like to make an audacious claim for this show and this group of talent: both are highly unconventional. This claim may sound strange to those for whom nothing seems more conventional than landscape painting—those who regard real Art (with a capital “A”) as a parade of innovations and “vanguard” movements which centuries ago marched across the landscape, did all they could with it, and moved on. “Landscapes have been done—they’re old hat.” Their supposed obsolescence is indeed, as the cliche suggests, no more than a meaningless turn of fashion—another arbitrary convention. Call it what you like, I call it ignoring the earth. To those who argue that Art has moved on from landscape painting, that we’re done with pictures of nature, I say, nature will decide when she is done with us.

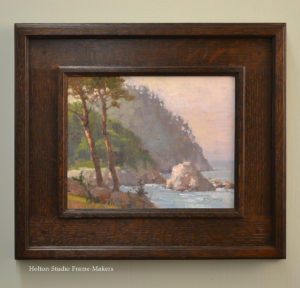

Bill Cone, “Pacific Edge”

But, some might object, how can something so traditional as landscape painting be considered unconventional? The answer is that tradition and convention are not the same. Conventions are dead, but traditions are living, else they cease to be traditions; conventions are mindless and unseeing, but traditions are alive to the surrounding and changing world.

Things that matter to civilization tend to accrue cultural traditions that acknowledge, honor and uphold them. California’s rich landscape painting tradition is intimately related to another of the state’s great contributions to the world, environmentalism—a relationship embodied in the close friendship between the great painter William Keith and Sierra Club founder John Muir. As a native Californian, I can scarcely imagine our state’s culture and identity without these intimately connected traditions.

The antidote to convention isn’t arbitrary novelty, iconoclasm and irreverence. That way lies nihilism and darkness. The true antidote to convention is going out into the reality of nature itself, going out into the light and pausing to see directly and clearly, see the world for what it is. If you want to see in new ways, set your eyes on the ever-changing landscape and the sunlight upon it.

And that’s what these artists have done. Every painting in this show, while inspired by a tradition, is anti-conventional—absolutely new. Each work not only represents a place but is evidence of time taken to see, and deliberate effort of extraordinary practiced powers to depict that place as it is, to be receptive to it, and to reveal it honestly and directly—and not as it literally appears through the lens of the eye but as it’s perceived through the eye and the heart. Not one of these paintings has been painted before, nor could any ever be painted by another human being. Not one of these scenes has been seen in this way before. This approach to painting is the very definition of unconventional.

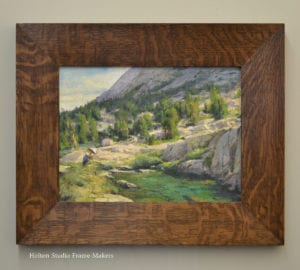

Paul Kratter, “Between Fog and Sun—Point Lobos”

We do well to drop for a moment our modern love of novelty (or a peculiar notion of novelty that somehow blinds us to things authentically alive) and consider an immutable truth about art: A painter paints because he or she wants other people to see something. A painting—and an exhibit, as well as a picture frame, by the way—says: Consider this. This matters. In the case of this show, “Beloved California,” what matters is this place where we are—the land before our eyes, the land beneath our feet, the land that feeds and sustains us. What matters first of all is the land itself; but next of all, how we view the land—our humility before it, our consideration and veneration for it, our recognition that the land is our very life. So I and these painters don’t only want you to observe the landscape, nor simply admire the painters’ skills of depiction. We want you to witness this land through deeply, intimately engaged eyes. Consider this. This matters.

Ernesto Nemesio, “Bill at Work”

If part of the mission of Art is to be visionary, to show a way forward, to break with careless conventions and bad old habits like ignoring the well-being of the earth, California’s tradition of landscape painters does just that. It is a tradition of hope and renewal. These painters are not only capturing the light on the land where we live but are themselves providers of light for the only way ahead—along a path toward greater consideration of the earth, toward living better on the land, toward taking greater care of the particular place on the planet each human community inhabits.

For us, that place is our beloved California.

—Tim Holton

The Opening—

- Visitors chat with Mark Farina, right

- Tim greets birthday boy Paul Kratter

- Artists Ernesto Nemesio and Kevin Brown

- Paul Roehl and Tim Holton chat

- Enjoying Terry Miura’s paintings

- Jessie’s pleased!

- Enjoying Paul Roehl’s paintings

- Ernesto Nemesio meets a fan

- Cellist Gael Alcock performed