The work of Anders Zorn (Sweden, 1860–1920) is a great example of the concern artists of his day had for sustaining the unity of all the arts. He was among the many painters who insisted—even as they pursued painting for its advantageous status in the commercial market—on understanding their own artistic specialty as supported by, and dependent upon architecture, the humbler handcrafts and nature.

As Walter Crane put it in The Claims of Decorative Art, “It is certain that painting and sculpture…cannot be in a good state, cannot reach any perfection where the multitudinous arts that surround and culminate in them – that frame them in, in short – are not also in vigorous health and life.” Zorn, who most directly absorbed the ideals of the English design reform movement while in Britain for six years in the 1880’s, clearly shared Crane’s notion and longed to restore the fine arts with architecture and the decorative arts. The great aim was to re-frame our daily lives in the vernacular arts—an ideal materially and naturally expressed in picture framing.

This past Sunday I saw the Anders Zorn show at the Palace of the Legion of Honor in San Francisco. You have less than two weeks to get to it; get to it. Not enough can be said for this outstanding painter — highly acclaimed in his day (regarded on par with John Singer Sargent), but fallen far too much into the background in the past several decades. This show is the first major American Zorn retrospective in nearly a century, and is something to revel in and be very grateful for. I found much to ponder and inspire in regards to the art of framing and the place of art.

How Zorn framed himself—

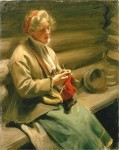

Here are three Zorn self-portraits, one without the picture frame, but with the artist in a folk setting—himself framed by traditional clothing and architecture. The other two are notably set in plain wood frames.

Unfortunately, almost nothing is said in the show or catalog about the frames. Yet in light of the conventional frames of the day, many of the choices are striking. Most of all, they should be considered as consistent with the values of folk life—and the artist’s valuing of folk life—in  his native village of Mora in rural Sweden even as he enjoyed enormous international success. Zorn’s society portraits — he had an astonishing career in the U.S., painting two presidents and numerous members of the gilded age elite — are set in conventional ornate gilt frames to the demands, no doubt, of his clients (see example at right). But for other work, the artist chose much plainer and more humble frames. While many of these were nonetheless gilded or painted gold, his later frames were dark wood. Thus Zorn’s work represents the fascinating intersection of elite and popular places of art that nineteenth century painters struggled to reconcile. Some of the best examples from the show were nowhere to be found online. Research did turn up a few examples—and one very unusual and humorous design.

his native village of Mora in rural Sweden even as he enjoyed enormous international success. Zorn’s society portraits — he had an astonishing career in the U.S., painting two presidents and numerous members of the gilded age elite — are set in conventional ornate gilt frames to the demands, no doubt, of his clients (see example at right). But for other work, the artist chose much plainer and more humble frames. While many of these were nonetheless gilded or painted gold, his later frames were dark wood. Thus Zorn’s work represents the fascinating intersection of elite and popular places of art that nineteenth century painters struggled to reconcile. Some of the best examples from the show were nowhere to be found online. Research did turn up a few examples—and one very unusual and humorous design.

A glimpse of Zorn’s favorite, and very plain, frames—

The first picture is an odd view, but at least shows the extremely plain frame choice—and on a painting significant to Zorn, not only because the subject is his wife, Emma, but because it is his first oil painting after establishing himself as a watercolorist. After this piece, he would focus on oil painting. (Note how the bevel echoes the angled planes of Emma’s newspaper.) The next two are very typical Zorn frames — gilt (or gold painted) wood, the wood showing through plainly. The last — quite a pot-boiler; as though the figure weren’t seductive enough, a very mischievous cupid’s aiming his arrow right at you!—sustains the background of the painting in a muted pattern on a plain flat frame. Of the frames I saw in the show, hardly any were as plain as the first portrait; nearly all had some detail. (Some were very similar to our No. 183 “Maybeck.”)

- Anders Zorn, “Portrait of Emma Zorn”

- Anders Zorn, “Anna”

- Anders Zorn, “Karleksnymf”

The key frame—

Typically, stretched canvases are on stretcher bars that include “keys” in the corner—thin wedges fit into slots at the joints of the stretcher and that may be driven into the slots to spread the joints, expanding the stretcher bars and thereby tightening the canvas. Zorn appears to have been very fond of the stretcher key image, as seen by the backgrounds of the two portraits below, and cleverly adapted it for the front of a painting, to decorate the corners of a frame. It’s a celebration of joinery and the craft of painting, but at the same time, for a modern urban scene, an aptly utilitarian motif!

- Anders Zorn, “Self-Portrait,” 1889

- Anders Zorn, “Emma Zorn”

- Anders Zorn “Omnibus, Paris,” 1882

The rural frame and the industrial frame—

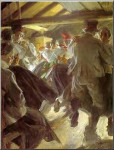

The “Omnibus” was one of several depictions of urban industrial life that Zorn witnessed during his stays in London, Paris, Hamburg and the U.S. He was able to find beauty in its utilitarian dreariness, but there’s no denying that its workers in black, enervated by their jobs, passively being shuttled around as commodities, like the packages on the main figure’s lap in each image, or as interchangeable parts in the industrial-commercial machine, contrast sharply—and unfavorably—with the cheerful dress and vital, if hard, life of Mora. Here is the “Omnibus” along with a similar painting, the two contrasted with two depictions of life in Zorn’s Swedish village.

Anders Zorn loved boating and swimming, and after enjoying his paintings of life on the water at Mora, we feel the weight of Hamburg’s industrial harbor, the life of the boatman framed not by green and rocky shores and bright clear water, but by menacing steel ships and black slurry, not a glimpse of natural life to be seen.

Zorn and the frame of the daily life and arts of the people—

Anders Zorn framed his own life in the natural landscape of Mora, and in the local folk arts and architecture, and communal festivities of the village. He especially loved the Midsummer celebration and the enjoyment of the long daylight hours, and his “Midsummer Dance” has been embraced by his country as a national treasure. His home was built and furnished in the vital local arts (it’s preserved and accessible to the public). On the grounds he built an open-air museum with examples of vernacular farm buildings. There’s also a textile museum. Starting out as a wood carver, he approached painting as a craft first (the “key” frame reflecting this). His paintings—at least when they’re not of nudes in a totally natural landscape—celebrate traditional costume and daily chores, buildings and hand crafts. He chose for subjects ordinary citizens of Mora, at work and play.

- Anders Zorn, “Midsummer Dance”

- Anders Zorn, “Entering the Cellar,” 1916

- Anders Zorn, “Mora”

This show’s lack of regard for the frames is a great example of the failure of contemporary museums to focus attention on and explore an artist’s understanding, through his approach to framing, of the profound question of the place of art. I wish museum curators, in their tendency to isolate painting from the other arts, would at least let us know when a frame is known to have been chosen by the artist. We can, in any case, piece together the story for ourselves using the many clues. And Zorn’s is a story of a painter who reached the greatest standing but refused to separate his art from the arts generally, or to be seduced by the new urban and commercial-industrial order, but continued to appreciate and to cultivate his vital rural roots. Having lived in Scandinavia in my youth, I felt the vigor of a living folk culture in which personal identities drew from real places, their landscapes, work and traditions. Zorn’s pictures of people working and living in harmony with nature are all portraits of a truer humanity than most of us know today. The artist painted with his feet planted on the ground and upon an understanding of the true place of art — in our joy in our daily life on the earth.

More on the show, “Anders Zorn: Sweden’s Master Painter”…

See the Zorn house interior in the video here…

« Back to Blog

Hi, Tim.

While browsing auctions I came upon engravings by Zorn. A subsequent Google search brought me to your article about how Zorn framed his work. Very interesting. Thank you.