I need to write up the story of how reproduction French baroque gilt frames came to be regarded as suitable for impressionist paintings, but the absurdity of it is plain enough to see.  Here’s a good example of a landscape, “Woodstock,” by one member of New York’s leading circle of impressionist painters. Hayley Lever hung out and painted with the likes of Robert Henri, Ernest Lawson, George Bellows, John Sloan and William Glackens. This 16″ x 20″ painting came to us recently in the gilt frame at right. We re-framed it in a No. 17.4 CV—3″ carved flat mitered profile in stained quartersawn white oak with a black slip. What’s astonishing about the gilt frame is that it is obviously meant to signal that the painting has extraordinary importance and value but could only have been chosen by someone who either didn’t see the painting at all or didn’t care if anyone else saw the painting—except, perhaps, as a work of art in the abstract, something we’re taught to value and to use to impress others with, but which we don’t need to trouble ourselves to really look at. There is nothing about the frame that’s the least bit sympathetic to or resonant with the painting. Both the fussy detail of the frame and the gold color pull the eye away from the picture. We actually struggle to see the painting, and what the painter worked so hard to put before our eyes.

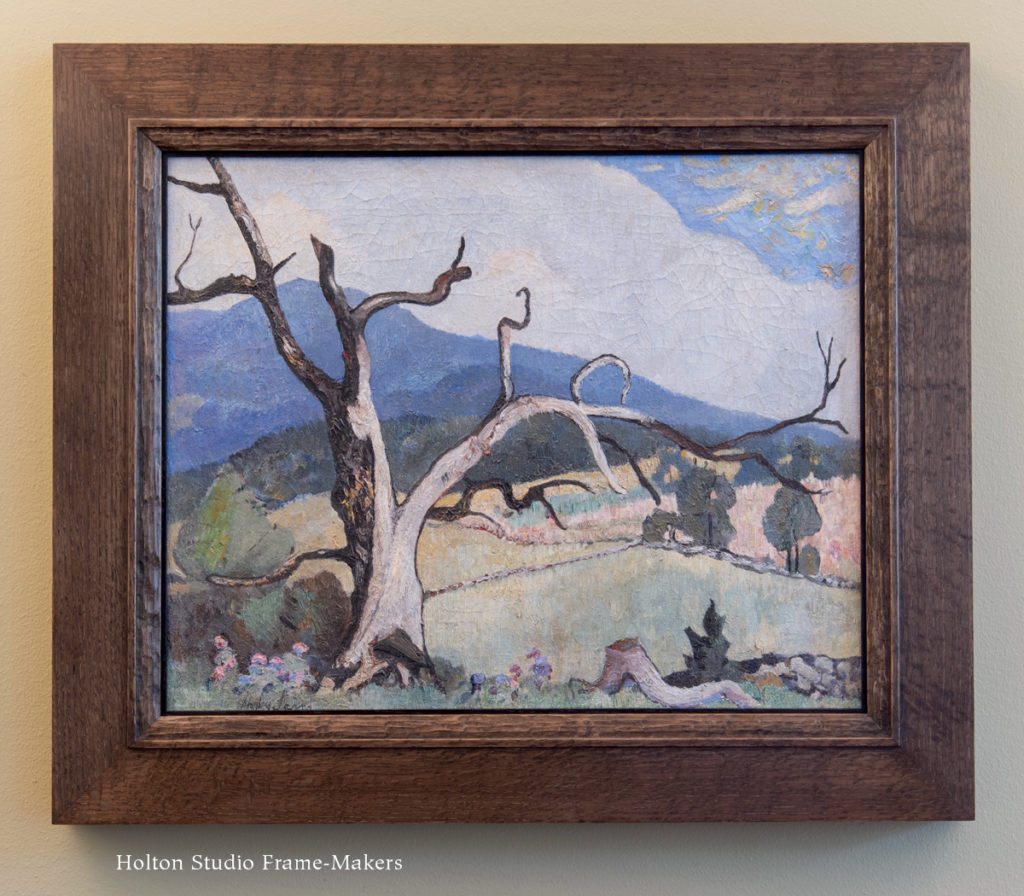

Here’s a good example of a landscape, “Woodstock,” by one member of New York’s leading circle of impressionist painters. Hayley Lever hung out and painted with the likes of Robert Henri, Ernest Lawson, George Bellows, John Sloan and William Glackens. This 16″ x 20″ painting came to us recently in the gilt frame at right. We re-framed it in a No. 17.4 CV—3″ carved flat mitered profile in stained quartersawn white oak with a black slip. What’s astonishing about the gilt frame is that it is obviously meant to signal that the painting has extraordinary importance and value but could only have been chosen by someone who either didn’t see the painting at all or didn’t care if anyone else saw the painting—except, perhaps, as a work of art in the abstract, something we’re taught to value and to use to impress others with, but which we don’t need to trouble ourselves to really look at. There is nothing about the frame that’s the least bit sympathetic to or resonant with the painting. Both the fussy detail of the frame and the gold color pull the eye away from the picture. We actually struggle to see the painting, and what the painter worked so hard to put before our eyes.

As I’ve often explained, the use of wood instead of gold obeys the simple optical principle that the eye goes to light, and therefore a shadow value for the frame effectively spotlights the painting to help do what the painter desires above all: for us to see what he or she has painted. If we take the time to see a painting, the frame design suggests itself with a simple nod to the elements of form, color, line and texture in the picture, as well as to its spirit. Hayley Lever wanted us to see the natural, rustic beauty of the hills around Woodstock (not place us inside a banker’s apartment in Paris!). He made a painting to provide a record of some permanence of the impression, visual and emotional, that moved him that particular day and season from that particular vantage point.

As I’ve often explained, the use of wood instead of gold obeys the simple optical principle that the eye goes to light, and therefore a shadow value for the frame effectively spotlights the painting to help do what the painter desires above all: for us to see what he or she has painted. If we take the time to see a painting, the frame design suggests itself with a simple nod to the elements of form, color, line and texture in the picture, as well as to its spirit. Hayley Lever wanted us to see the natural, rustic beauty of the hills around Woodstock (not place us inside a banker’s apartment in Paris!). He made a painting to provide a record of some permanence of the impression, visual and emotional, that moved him that particular day and season from that particular vantage point.

The frame made as a result of seeing the painting helps others, in turn, to see the painting. Beginning with the plain use of wood, the frame sustains and projects the love of nature that moved the artist in the first place. Everything about a frame should be subordinated to the beauty of the natural material it’s made of. The carving, used on the innermost element of the frame profile, conveys the character of the wood—its density and resistance to the hand, and brings back to the milled lumber the wildness of its natural texture, which the painter celebrates on the surface of the dominant tree. That texture is throughout the picture in not only the things depicted but the brushwork. The carving is also the result and pleasing evidence of engagement of the human hand with the wood—in our divine duty, to use William Morris’s wonderful phrase, “to help in the work of creation.” And finally, it is evidence of the sacrifice of labor to something beautiful and worthy of sacrifice.

The carved sight edge element is a convex or flattened ovolo or “cushion” form sustaining the form of several things in the painting including the trees, the hills and the clouds. The narrow, raised strap or band outside the carved cushion echoes the confident and strongly defining line work, which is also picked up by the black slip. We could have gone with a slope or cushion for the overall form of the frame, but the flat felt right, probably because of the guiding principle of impressionism to respect and accept the flat surface of the canvas and the art of painting as a frank treatment of flat surface, rather than imposing on that surface the illusion of three dimensions.

See more before-and-after pictures of paintings that came to us in gold frames, and that we re-framed in dark wood, here.

Learn more about Hayley Lever here, and on the website of Questroyal Fine Art and Gavin Spanierman’s website.

« Back to Blog