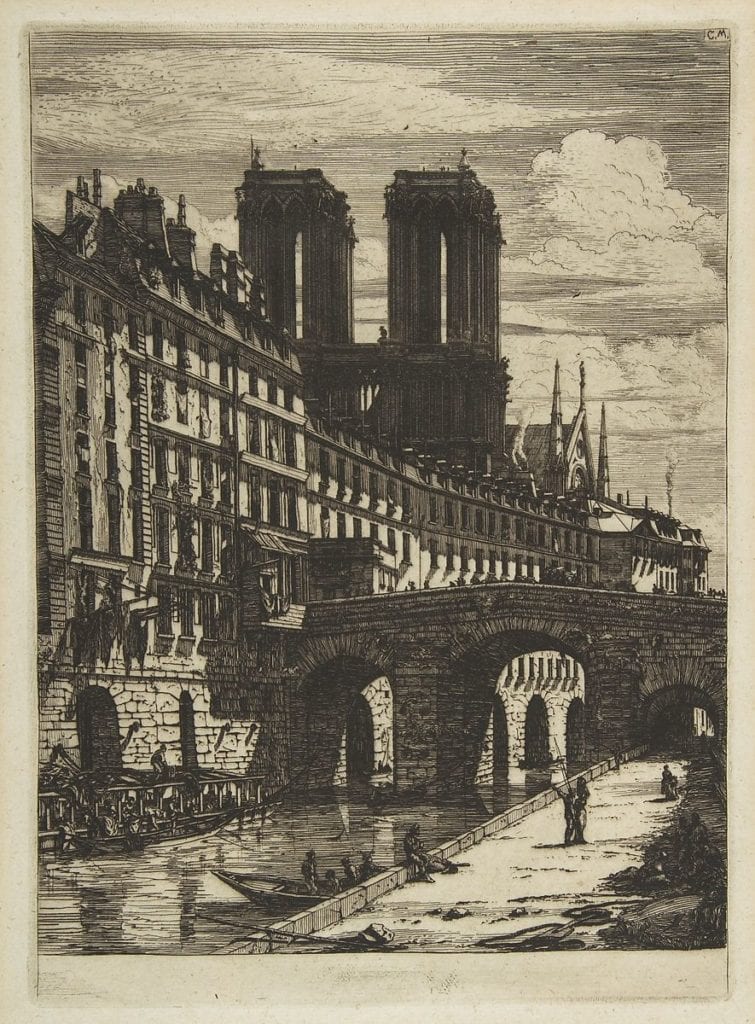

It is not difficult to find lovingly created pictures of Notre Dame, that great piece of the commonwealth we call civilization, that great work of devoted labor that burned yesterday as the world watched in horror. Why are they easy to find? Because the building has been so loved. Here are three prints from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, all by Charles Meryon (1821-1868). The first dates from 1854, and captures the centrality of “Our Lady,” watching over the everyday, common life of the city.

Charles Meryon (1821-1868), “The Apse of Notre Dame,” 1854. Etching, 6-1/2 x 11-13/16. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

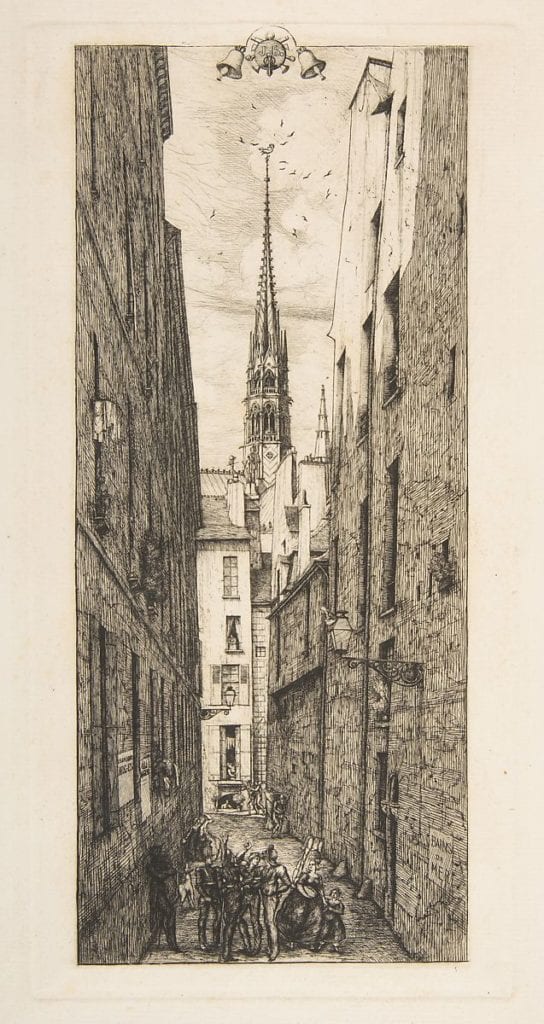

Notre Dame’s iconic spire, which was destroyed by fire yesterday. Charles Meryon, “Rue de Chantres, Paris,” 1862. Etching. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A couple years after Monsieur Meryon made this print, two young Englishmen, William Morris and his friend Edward Burne-Jones, toured the cathedrals of France and were changed forever by all that those great creations represented of what the arts could be, and eternally are—”the expression,” as Morris would say (summing up the meaning of John Ruskin’s “The Nature of Gothic”), “of man’s joy in his labor.” There may be no more heartfelt tribute to these cathedrals and their builders than the words below, excerpted from Morris’s 1856 “Shadows of Amiens”:

…I think those same churches of North France the grandest, the most beautiful, the kindest and most loving of all the buildings that the earth has ever borne; and, thinking of their past-away builders, can I see through them, very faintly, dimly, some little of the mediaeval times, else dead, and gone from me for ever,— voiceless for ever.

And those same builders, still surely living, still real men, and capable of receiving love, I love no less than the great men, poets and painters and such like, who are on earth now, no less than my breathing friends whom I can see looking kindly on me now. Ah! do I not love them with just cause, who certainly loved me, thinking of me sometimes between the strokes of their chisels; and for this love of all men that they had, and moreover for the great love of God, which they certainly had too; for this, and for this work of theirs, the upraising of the great cathedral front with its beating heart of the thoughts of men, wrought into the leaves and flowers of the fair earth; wrought into the faces of good men and true, fighters against the wrong, of angels who upheld them, of God who rules all things; wrought through the lapse of years, and years, and years, by the dint of chisel, and stroke of hammer, into stories of life and death, the second life, the second death, stories of God’s dealing in love and wrath with the nations of the earth, stories of the faith and love of man that dies not: for their love, and the deeds through which it worked, I think they will not lose their reward.

We may forgive Morris if we think him a bit too sentimental here. He was a young man in search of purpose, who in Amiens, Rouen, and Paris had not only discovered that purpose, but witnessed and become possessed by a stupendous power that is not only some of the best of what human beings can make and build, but a power that is above all the spirit expressed by all the good work that we can do: Love. It is a power to ponder as we reflect on the meaning of Notre Dame, Our Lady and our common wealth, built in love of humankind.

« Back to Blog