Last Saturday’s post on framing a couple of HW Hansen watercolors, which we framed close, ended with the observation that, “Framing close means that the frame is close to the picture; no mat separates them. But there’s a second meaning, at least as important, which is that, in a picture with perspective, a mat creates separation in the illusionary third dimension as well, pushing the subject not only away from the frame but away from the viewer. This explains the more intimate, as well as more unified, effect of a picture framed close.” I’ve been wanting to do a post here on a fascinating point made by John Ruskin directly addressing this aspect of framing close. (Given his particular example, the timing’s all the better as Christmas is close!) Found in Fors Clavigera, Letter LXXVI, it’s an observation on this painting by the early 15th century Florentine painter Filippo Lippi, representing the Madonna:

Fillipo Lippi, “Madonna with Child and two Angels,” ca. 1465. (Ufizzi)

The first thing you are to observe in it is that the figures are represented as projecting in front of a frame or window-sill. The picture belongs, therefore, to the class meant to be, as far as possible, deceptively like reality; and is in this respect entirely companionable with one long known in our picture-shops, and greatly popular with the British innkeeper, of a smuggler on the look-out, with his hand and pistol projecting over the window-sill. The only differences in purpose between the painter of this Anglican subject and the Florentine’s, are, first, that the Florentine wishes to give the impression, not of a smuggler’s being in the same room with you, but of the Virgin and Child’s being so; and, secondly, that in this representation he wishes not merely to attain deceptive reality; but to concentrate all the skill and thought that his hand and mind possess, in making that reality noble.

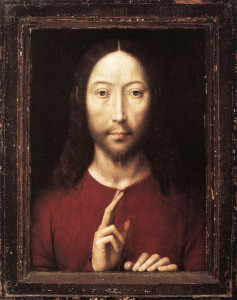

The Hans Memling portrait of Christ at left uses the frame in a similar way—although it uses the actual frame, not a frame painted on the panel—to make the subject’s presence as intimate and real as possible. These subjects are the embodiments of ideals, and the artist wants us to connect with them and truly live with them.

The best reason to frame close is that it’s so effective—it makes the subject of the picture feel more present and real, and the frame and picture feel more unified and the framed picture feel more like part of the room. In fact it’s puzzling that we started framing pictures with the opposite idea in mind — of pushing the picture away and isolating it. It rarely seems to occur to us to bring our imaginative powers to bear in the way these painters clearly meant us to, conveying and encouraging admiration and even reverence for something (not necessarily a religious figure; it might be for a person or landscape or past event). Since the 18th century rise of aestheticism, we’ve treated works of art as objects for isolated contemplation composed of elements like color and form that act on the senses independent of any meaning the subject matter might have—or abandoned any realism whatsoever in pursuit of abstraction. With this as our object, we’ve used frames to separate our pictures from the distractions of the surrounding world and push them away, keeping them at arm’s length, in order to get a better look.

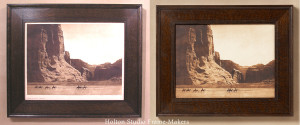

Two examples of a photo, ES Curtis’s “Canon de Chelly” (by Mountain Hawk Prints), with some margin showing and framed truly “close”—all the way to the image

But if pictures have any meaning apart from providing moments of idle curiosity or as trophies or tokens of wealth and status—which for most of us they do—then Ruskin’s lesson is very important to how you want to frame your pictures. If you have a picture of something or someone you love (no matter if it’s religious or not; don’t let the examples here obscure the real point), this use of framing to bring the picture’s subject closer to you and make it more real and present is very, very powerful. It can be quite refreshing to re-frame a picture that’s been matted or, with some other framing treatment, stuck in a setting that’s isolating. (Read my article in Picture Framing Magazine on this topic.)

Here are more examples by Lippi, showing his use of the frame as a window to make his subjects real and present to the viewer:

- Another Madonna & child by Lippi, ca. 1465

- “Madonna & Child,” ca. 1440 National Gallery, Washington

- “Portrait of a Woman with a Man at a Casement,” ca. 1440–44 (Metropolitan Museum)

- “Virgin & Child,” ca. 1450-60 (The National Gallery, London)

More paintings by Hans Memling, with frames used to bring the subject close to the viewer—

- Hans Memling “Portrait of a Man with a Pink,” ca. 1475. The Morgan

- Memling, “Virgin & Child”

- Sibylla Sambetha, 1480. (Oil on oak)

And finally, a painting of Henry VI using the same idea—note the shadow of the frame painted in the background:

King Henry VI by unknown English artist. Oil on panel, circa 1540. (National Portrait Gallery)

« Back to Blog