John Ruskin called Venice the Paradise of Cities. And so it is. Last month I spent five days in Paradise, which I can report is—curiously enough—populated mostly by tourists who don’t plan to stay long. (Maybe they all have bad consciences and don’t think they really deserve to be there).

Two other things to know about Paradise: first, in Paradise, life is all about Paradise, not the will of its ruler, heavenly or earthly (as it was in many old cities), nor your own getting ahead (as it is in all modern cities); and, second, it’s made by hand. It’s a work of substantial devotion. These two things must be considered together, because Rome was also built by hand (and certainly not in a day, as a tour guide there confirmed for me), but that city was built by slaves who must have hated the place along with its tyrannical rulers. Venice, on the other hand, is a work of love and devotion for a city, by a city of free craftsmen. The Serene Republic (“La Serenissima”), as the name implies, was built on the sovereignty of the people, not the Doge, whose power was carefully kept in check (that’s why he was a doge—or duke—and not a king).

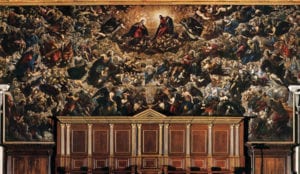

Tintoretto’s massive (82 foot long), “Il Paradiso,” 1588, in the Main Hall of The Doge’s Palace in Venice

And the infinite variety of detail unified in a whole city (well, the medieval parts at least) as a work of art is the product of countless artisans given relatively free reign, governed primarily by their individual practiced artistic powers (cultivated, in many if not most cases, over generations), their pride and joy in those powers, combined with their love for their city and their communal life. (See Ruskin’s “The Nature of Gothic” for much more on that.) That fact is visible and evident at every turn, and is what makes you know when you’re there that you are in something pretty close to Paradise. Also there are no cars. That is, the former Serene Republic is still relatively serene. It’s not only built by human beings, it’s built for human beings, not machines. It’s humane, and human scale, and—being something people really believed in—it’s built to last. Therein lie a few lessons for our modern city planners and architects—well, for all of us, in fact.

While many cities are homes to great works of art, the architecture of the whole city of Venice is one big work of art, one great frame for the life of the city—a frame to honor not only a particular place but the ancient idea and ideal of civitas, and true civilization. At the center of this frame and great work of many arts all cooperating to one end is, of course, Piazza San Marco, the great public square, a place for the people of the city to gather, and its renowned cathedral built for the whole city to worship together. Worth noting, too, is the piazza’s medieval clock tower, and especially the composition of its face: above the clock is a sculpture of the Madonna and child; but above that symbol of the Christian Church is the winged lion, symbol of Venice’s patron saint, St Mark, and so of the city of Venice itself. The meaning of this arrangement, as any true Venetian will tell you with a mischievous smile, is that the City is above the Church. In any case, evidence abounds that the devout civic religion of Venice was, if not exactly superior to, was at least inseparable from the faith taught by the Church. If you couldn’t serve the city favored by one of its primary saints, how could you possibly serve the will of the saint and the church? If you couldn’t commune with the civic body, how could you possibly commune in the body of Christ that is the Church? If you couldn’t believe in the immediate heavenly city, how could you possibly believe in an eternal Heavenly City—or a Heavenly Father?

So the adjacent St Mark’s Basilica not only frames many, many works of art including spectacular mosaics—4000 square meters of them!—that are part of the frame, but, more importantly, must be understood as once being the central frame of the civilized life of La Serenissima. And how did the people of Paradise frame the entrance to their most sacred temple built by and for the communion of the citizenry? This is how Ruskin, in St Mark’s Rest, his guide to and meditation on Venice, described the underside of the central arch on the front of the basilica:

I have been speaking hitherto of the front of the arch only. Underneath it, the sculpture is equally rich, and much more animated. It represents, — What think you, or what would you have, good reader, if you were yourself designing the central archivolt of your native city, to companion, and even partly to sustain, the stones on which those eight Patriarchs were carved — and Christ?

The great men of your city, I suppose, — or the good women of it? or the squires round about it? with the Master of the hounds in the middle? or the Mayor and Corporation? Well. That last guess comes near the Venetian mind, only it is not my Lord Mayor, in his robes of state, nor the Corporation at their city feast; but the mere Craftsmen of Venice — the Trades, that is to say, depending on handicraft, [including] the shipwrights,… the givers of wine and bread…the carpenter, the smith, and the fisherman…

[T]he order…is then thus:

1. Fishing.

2. Forging.

3. Sawing. Rough carpentry?

4. Cleaving wood with axe. Wheelwright?

5. Cask and tub making.

6. Barber-surgery.

7. Weaving.

Keystone—Christ the Lamb; i.e., in humiliation.

8. Masonry.

9. Pottery.

10. The Butcher.

11. The Baker.

12. The Vintner.

13. The Shipwright. And

14. The rest of old age ?

Butchers? Potters? Carved over the central entrance to one of the world’s greatest churches??? These stones speak, Ruskin points out. These stones that frame a great work of art speak strange and forgotten things. They say that a great work of art should be humble enough to acknowledge its debt and its service to the ordinary workers and the most commonplace arts and labors. The difference between ordinary work and fine art is often only the difference of greater devotion and purpose. And that is how some of the world’s greatest artists, builders of the great Basilica San Marco, framed art, and their understanding of what art is, and who is an artist—the true place of art.

So here, via Ruskin, is another lesson from Paradise. Human beings can build, and have built, cities of heavenly beauty and joy—cities that honor and give pride of place to the wonderful power of the mighty hand. Our hands, as Venice proves, have the power to build true civilization, a heavenly city built by all its citizens, built for all its citizens—right here on Earth. In the opening words of the final volume of Modern Painters, Ruskin questions the entire conventional reading of Genesis. “What can we conceive of that first Eden which we might not yet win back, if we chose?,” he asks. It turns out that whole “curse of labor” thing is a fallacy. Following Ruskin’s lead, the great Arts and Crafts architect WR Lethaby wrote, “Hidden in early Christian teaching are ideas which we never hear of now. One of these was the thought that the ‘curse’ was a blessing. It is probable, indeed, that the whole glorious unfolding of mediaeval art sprang from a thought of the heroism of labour.” He found in one medieval explanation of depictions of Genesis that Adam’s spade and Eve’s spindle were not the tools to which they were condemned but “the instruments of their redemption”. We thought that spell we had in the Garden of Eden was one big holiday, life on the dole, that Paradise was labor-free, and that’s why, since our fall from grace, we have to work, and that our work has to be miserable. Nope. Turns out Paradise is, in fact, very labor intensive. Sure, working the stones of Venice could be as hard as working stones anywhere. But there, in the Paradise of Cities—to what great purpose! And having a worthy, honorable and enduring purpose—and working toward the purpose of a wealth in which the workman enjoys a share, a wealth that honors him, and welcomes and expects him to enjoy the opportunity to express himself in his work, and his joy in helping in the work of creation—makes all the difference in how he feels about his labors.

But not only that. Turns out that the whole story that we’ve been permanently booted out of Paradise isn’t true. It can’t be—I was just there!

Yes, I would’ve happily stayed. In any case, I sure took home a good lesson about how they once framed art in Paradise, and maybe how it might be framed again—if we’re good, honest and true to our work and to the greater good of the places where we live.

FOOTNOTE: Many argue that Venice has a checkered history, containing many despicable deeds, and should in no way be regarded as Edenic. But to them I’d have to say that the material evidence abundantly proves the civic values and devotions of a people who, taken as a whole and for a substantial portion, certainly not all, of their history, and whether or not their values were shared by everyone at all times, at least generally and characteristically demonstrated and practiced a faith in res publica—public matters, subordinating personal power and individual interest to the interests of the commonwealth. And, further, they did so with extraordinary engagement with the materials of the natural creation, and used their lives to cultivate and substantially contribute to the creation. They were, in short, on to something. And to live among such people would be, at least for me, Paradise enough.

Read “What Ruskin Saw Framed in the Stones of Florence”…

Read “Framing a Good Life: Lessons from the Stones of Siena”…

« Back to Blog