The following lecture was delivered by Ruskin at Oxford University in 1872, and was published in the volume titled Ariadne Florentina. I am publishing it on my own website because it is the most important testimony to the significance of picture frames by the greatest art critic of the nineteenth century. In it, Ruskin asks his audience (in section 59), “Have you ever considered, in the early history of painting, how important also is the history of the frame-maker? It is a matter, I assure you, needing our very best consideration.” Although the reference to frames is brief—one might expect from that quote that he’d go on to consider frame history in more particular detail, but he doesn’t—it serves as the climax to an elaborate and thorough argument, holding up as emblematic of his lecture’s theme an image from a medieval bas relief that features a frame. And the reason Ruskin believes that the art of the frame-maker needs our very best consideration is that, while in the modern era the art of painting took an arrogant and insular stance toward the other arts and crafts, in the middle ages painters had a humbler attitude toward more ordinary craftsmen, including their closest collaborators, frame-makers. Ruskin was, in essence, asking his audience to reconsider an art form toward which their age had become indifferent, an art form it had badly denigrated and debased; and to consider the noble place the art of the frame-maker had once held in the eyes of even the greatest artists of Florence. But even more profound is the lesson underlying such bygone humility and consequent cooperation and relative equality between artists and artisans: the primal, natural and ineluctable unity of the arts, and more largely the unity and cohesion of a thriving, wholesome human society.

The following lecture was delivered by Ruskin at Oxford University in 1872, and was published in the volume titled Ariadne Florentina. I am publishing it on my own website because it is the most important testimony to the significance of picture frames by the greatest art critic of the nineteenth century. In it, Ruskin asks his audience (in section 59), “Have you ever considered, in the early history of painting, how important also is the history of the frame-maker? It is a matter, I assure you, needing our very best consideration.” Although the reference to frames is brief—one might expect from that quote that he’d go on to consider frame history in more particular detail, but he doesn’t—it serves as the climax to an elaborate and thorough argument, holding up as emblematic of his lecture’s theme an image from a medieval bas relief that features a frame. And the reason Ruskin believes that the art of the frame-maker needs our very best consideration is that, while in the modern era the art of painting took an arrogant and insular stance toward the other arts and crafts, in the middle ages painters had a humbler attitude toward more ordinary craftsmen, including their closest collaborators, frame-makers. Ruskin was, in essence, asking his audience to reconsider an art form toward which their age had become indifferent, an art form it had badly denigrated and debased; and to consider the noble place the art of the frame-maker had once held in the eyes of even the greatest artists of Florence. But even more profound is the lesson underlying such bygone humility and consequent cooperation and relative equality between artists and artisans: the primal, natural and ineluctable unity of the arts, and more largely the unity and cohesion of a thriving, wholesome human society.

The treatment of the “fine” art of painting in his own age, especially in the hands of the Royal Academy, as more or less the sum total of the entire realm of Art, reflected for Ruskin fatal division not only within the greater spectrum of the arts, but between art and labor, and between art and life. So while in the prevailing conditions of his time the art of the frame had been degraded and used—or abused—to separate and isolate paintings, Ruskin saw in the medieval architecture of Florence that frames had once been treated as a noble art form and used to the opposite purpose—to connect and unify paintings and architecture. So while the lecture is in no way a typical lesson in the appreciation of a particular art form, it includes a resounding lesson in the appreciation of the single most important aspect of a frame’s true role: its power, even though subordinate to pictures, to connect our pictures and the ideals they embody to the architecture of our homes and so to our daily lives. Done right and done well, the art of the frame may help restore the primal unity of the arts, and unity of art and life.

It is this effort to restore the primal unity of the arts—not, as is generally believed, to elevate the lesser arts—that became the real mission of the Arts and Crafts Movement that Ruskin inspired. While it’s certainly not one of his more famous talks, the lecture’s message fully reveals the true animating spirit of Ruskin, as well as his most famous student and the other primary inspiration of the Arts and Crafts Movement, William Morris—both men who were deeply troubled by a disintegrating world, and wanted above all to put the world back together again.

(This is the second lecture in the volume, hence the section numbers start at 39 because they continue from the first lecture.)

39. From what was laid before you in my last lecture, you must now be aware that I do not mean, by the word ‘engraving,’ merely the separate art of producing plates from which black pictures may be printed.

I mean, by engraving, the art of producing decoration on a surface by the touches of a chisel or a burin; and I mean by its relation to other arts, the subordinate service of this linear work, in sculpture, in metal work, and in painting; or in the representation and repetition of painting.

And first, therefore, I have to map out the broad relations of the arts of sculpture, metal work, and painting, in Florence, among themselves, during the period in which the art of engraving was distinctly connected with them.[D]

40. You will find, or may remember, that in my lecture on Michael Angelo and Tintoret I indicated the singular importance, in the history of art, of a space of forty years, between 1480, and the year in which Raphael died, 1520. Within that space of time the change was completed, from the principles of ancient, to those of existing, art;–a manifold change, not definable in brief terms, but most clearly characterized, and easily remembered, as the change of conscientious and didactic art, into that which proposes to itself no duty beyond technical skill, and no object but the pleasure of the beholder. Of that momentous change itself I do not purpose to speak in the present course of lectures; but my endeavor will be to lay before you a rough chart of the course of the arts in Florence up to the time when it took place; a chart indicating for you, definitely, the growth of conscience, in work which is distinctively conscientious, and the perfecting of expression and means of popular address, in that which is distinctively didactic.

41. Means of popular address, observe, which have become singularly important to us at this day. Nevertheless, remember that the power of printing, or reprinting, black pictures,–practically contemporary with that of reprinting black letters,–modified the art of the draughtsman only as it modified that of the scribe. Beautiful and unique writing, as beautiful and unique painting or engraving, remain exactly what they were; but other useful and reproductive methods of both have been superadded. Of these, it is acutely said by Dr. Alfred Woltmann,[E]–

A far more important part is played in the art-life of Germany by the technical arts for the multiplying of works; for Germany, while it was the land of book-printing, is also the land of picture-printing. Indeed, wood-engraving, which preceded the invention of book-printing, prepared the way for it, and only left one step more necessary for it.

Book-printing and picture-printing have both the same inner cause for their origin, namely, the impulse to make each mental gain a common blessing. Not merely princes and rich nobles were to have the privilege of adorning their private chapels and apartments with beautiful religious pictures; the poorest man was also to have his delight in that which the artist had devised and produced. It was not sufficient for him when it stood in the church as an altar-shrine, visible to him and to the congregation from afar; he desired to have it as his own, to carry it about with him, to bring it into his own home. The grand importance of wood-engraving and copperplate is not sufficiently estimated in historical investigations. They were not alone of use in the advance of art; they form an epoch in the entire life of mind and culture. The idea embodied and multiplied in pictures became like that embodied in the printed word, the herald of every intellectual movement, and conquered the world.

42. “Conquered the world”? The rest of the sentence is true, but this, hyperbolic, and greatly false. It should have been said that both painting and engraving have conquered much of the good in the world, and, hitherto, little or none of the evil.

Nor do I hold it usually an advantage to art, in teaching, that it should be common, or constantly seen. In becoming intelligibly and kindly beautiful, while it remains solitary and unrivaled, it has a greater power. Westminster Abbey is more didactic to the English nation, than a million of popular illustrated treatises on architecture.

Nay, even that it cannot be understood but with some difficulty, and must be sought before it can be seen, is no harm. The noblest didactic art is, as it were, set on a hill, and its disciples come to it. The vilest destructive and corrosive art stands at the street corners, crying, “Turn in hither; come, eat of my bread, and drink of my wine, which I have mingled.”

And Dr. Woltmann has allowed himself too easily to fall into the common notion of Liberalism, that bad art, disseminated, is instructive, and good art isolated, not so. The question is, first, I assure you, whether what art you have got is good or bad. If essentially bad, the more you see of it, the worse for you. Entirely popular art is all that is noble, in the cathedral, the council chamber, and the market-place; not the paltry colored print pinned on the wall of a private room.

43. I despise the poor!–do I, think you? Not so. They only despise the poor who think them better off with police news, and colored tracts of the story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, than they were with Luini painting on their church walls, and Donatello carving the pillars of their market-places.

Nevertheless, the effort to be universally, instead of locally, didactic, modified advantageously, as you know, and in a thousand ways varied, the earlier art of engraving: and the development of its popular power, whether for good or evil, came exactly–so fate appointed–at a time when the minds of the masses were agitated by the struggle which closed in the Reformation in some countries, and in the desperate refusal of Reformation in others.[F] The two greatest masters of

engraving whose lives we are to study, were, both of them, passionate reformers: Holbein no less than Luther; Botticelli no less than Savonarola.

44. Reformers, I mean, in the full and, accurately, the only, sense. Not preachers of new doctrines; but witnesses against the betrayal of the old ones, which were on the lips of all men, and in the lives of none. Nay, the painters are indeed more pure reformers than the priests. They rebuked the manifest vices of men, while they realized whatever was loveliest in their faith. Priestly reform soon enraged itself into mere contest for personal opinions; while, without rage, but in stern rebuke of all that was vile in conduct or thought,–in declaration of the always-received faiths of the Christian Church, and in warning of the power of faith, and death,[G] over the petty designs of men,—Botticelli and Holbein together fought foremost in the ranks of the Reformation.

45. To-day I will endeavor to explain how they attained such rank. Then, in the next two lectures, the technics of both,–their way of speaking; and in the last two, what they had got to say.

First, then, we ask how they attained this rank;–who taught them what they were finally best to teach? How far must every people–how far did this Florentine people–teach its masters, before they could teach it?

Even in these days, when every man is, by hypothesis, as good as another, does not the question sound strange to you? You recognize in the past, as you think, clearly, that national advance takes place always under the guidance of masters, or groups of masters, possessed of what appears to be some new personal sensibility or gift of invention; and we are apt to be reverent to these alone, as if the nation itself had been unprogressive, and suddenly awakened, or converted, by the genius of one man.

No idea can be more superficial. Every nation must teach its tutors, and prepare itself to receive them; but the fact on which our impression is founded–the rising, apparently by chance, of men whose singular gifts suddenly melt the multitude, already at the point of fusion; or suddenly form, and inform, the multitude which has gained coherence enough to be capable of formation,—enables us to measure and map the gain of national intellectual territory, by tracing first the lifting of the mountain chains of its genius.

46. I have told you that we have nothing to do at present with the great transition from ancient to modern habits of thought which took place at the beginning of the sixteenth century. I only want to go as far as that point;–where we shall find the old superstitious art represented finally by Perugino, and the modern scientific and anatomical art represented primarily by Michael Angelo. And the epithet bestowed on Perugino by Michael Angelo, ‘goffo nell’ arte,’ dunce, or blockhead, in art,–being, as far as my knowledge of history extends, the most cruel, the most false, and the most foolish insult ever offered by one great man to another,–does you at least good service, in showing how trenchant the separation is between the two orders of artists,[H]—how exclusively we may follow out the history of all the ‘goffi nell’ arte,’ and write our Florentine Dunciad, and Laus Stultitiæ, in peace; and never trench upon the thoughts or ways of these proud ones, who showed their fathers’ nakedness, and snatched their masters’ fame.

47. The Florentine dunces in art are a multitude; but I only want you to know something about twenty of them.

Twenty!–you think that a grievous number? It may, perhaps, appease you a little to be told that when you really have learned a very little, accurately, about these twenty dunces, there are only five more men among the artists of Christendom whose works I shall ask you to examine while you are under my care. That makes twenty-five altogether,—an exorbitant demand on your attention, you still think? And yet, but a little while ago, you were all agog to get me to go and look at Mrs. A’s sketches, and tell you what was to be thought about them; and I’ve had the greatest difficulty to keep Mrs. B’s photographs from being shown side by side with the Raphael drawings in the University galleries. And you will waste any quantity of time in looking at Mrs. A’s sketches or Mrs. B’s photographs; and yet you look grave, because, out of nineteen centuries of European art-labor and thought, I ask you to learn something seriously about the works of five-and-twenty men!

48. It is hard upon you, doubtless, considering the quantity of time you must nowadays spend in trying which can hit balls farthest. So I will put the task into the simplest form I can.

1200 1300 1400

| 1250 | 1350 |

+ + + + +

Niccola Pisano |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | | |

Arnolfo |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | |

Cimabue |-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | |

Giovanni Pisano |-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | |

Andrea Pisano |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | |

Giotto |-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | |

Orcagna |-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | |

1400 1500 1600

| 1450 | 1550 |

+ + + + +

Quercia |-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Brunelleschi |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Ghiberti |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Donatello |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Luca della Robbia |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | | |

Filippo Lippi |-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

Giovanni Bellini |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | |

Mantegna |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | |

Verrocchio |-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | | | | |

Perugino |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | |

Botticelli |-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | |

Luini |-|-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | |

Dürer |-|-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | | |

Cima |-|-|-|-| | | | | | | | |

Carpaccio |-|-|-|-| | | | | | | |

Correggio |-|-|-|-|-| | | | | | |

Holbein |-|-|-|-|-| | | | | |

Tintoret |-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|-|

Here are the names of the twenty-five men,[I] and opposite each, a line indicating the length of his life, and the position of it in his century. The diagram still, however, needs a few words of explanation. Very chiefly, for those who know anything of my writings, there is needed explanation of its not including the names of Titian, Reynolds, Velasquez, Turner, and other such men, always reverently put before you at other times.

They are absent, because I have no fear of your not looking at these. All your lives through, if you care about art, you will be looking at them. But while you are here at Oxford, I want to make you learn what you should know of these earlier, many of them weaker, men, who yet, for the very reason of their greater simplicity of power, are better guides for you, and of whom some will remain guides to all generations. And, as regards the subject of our present course, I have a still more weighty reason;–Vandyke, Gainsborough, Titian, Reynolds, Velasquez, and the rest, are essentially portrait painters. They give you the likeness of a man: they have nothing to say either about his future life, or his gods. ‘That is the look of him,’ they say: ‘here, on earth, we know no more.’

49. But these, whose names I have engraved, have something to say–generally much,–either about the future life of man, or about his gods. They are therefore, literally, seers or prophets. False prophets, it may be, or foolish ones; of that you must judge; but you must read before you can judge; and read (or hear) them consistently; for you don’t know them till you have heard them out. But with Sir Joshua, or Titian, one portrait is as another: it is here a pretty lady, there a great lord; but speechless, all;–whereas, with these twenty-five men, each picture or statue is not merely another person of a pleasant society, but another chapter of a Sibylline book.

50. For this reason, then, I do not want Sir Joshua or Velasquez in my defined group; and for my present purpose, I can spare from it even four others:–namely, three who have _too_ special gifts, and must each be separately studied–Correggio, Carpaccio, Tintoret;–and one who has no special gift, but a balanced group of many–Cima. This leaves twenty-one for classification, of whom I will ask you to lay hold thus. You must continually have felt the difficulty caused by the names of centuries not tallying with their years;–the year 1201 being the first of the thirteenth century, and so on. I am always plagued by it myself, much as I have to think and write with reference to chronology; and I mean for the future, in our art chronology, to use as far as possible a different form of notation.

51. In my diagram the vertical lines are the divisions of tens of years; the thick black lines divide the centuries. The horizontal lines, then, at a glance, tell you the length and date of each artist’s life. In one or two instances I cannot find the date of birth; in one or two more, of death; and the line indicates then only the ascertained[J] period during which the artist worked.

And, thus represented, you see nearly all their lives run through the year of a new century; so that if the lines representing them were needles, and the black bars of the years 1300, 1400, 1500 were magnets, I could take up nearly all the needles by lifting the bars.

52. I will actually do this, then, in three other simple diagrams. I place a rod for the year 1300 over the lines of life, and I take up all it touches. I have to drop Niccola Pisano, but I catch five. Now, with my rod of 1400, I have dropped Orcagna indeed, but I again catch five. Now, with my rod of 1500, I indeed drop Filippo Lippi and Verrocchio, but I catch seven. And here I have three pennons, with the staves of the years 1300, 1400, and 1500 running through them,–holding the names of nearly all the men I want you to study in easily remembered groups of five, five, and seven. And these three groups I shall hereafter call the 1300 group, 1400 group, and 1500 group.

1300.

^

|

1240-1302 Cimabue +-+-+-+-+-+-+

|

1250-1321 Giovanni Pisano +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|

1232-1310 ARNOLFO -+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|

1270-1345 Andrea Pisano +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1276-1336 Giotto +-+-+-+-+-+

1400.

^

|

1374-1438 Quercia -+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|

1381-1455 Ghiberti +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1377-1446 BRUNELLESCHI +-+-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1386-1468 Donatello +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1400-1481 Luca +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

1500.

^

|

1431-1506 Mantegna -+-+-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1457-1515 Botticelli +-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1426-1516 Bellini +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1446-1524 PERUGINO +-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|

1470-1535 Luini +-+-+-+-+-+-+-

|

1471-1527 Dürer -+-+-+-+-+-

|

1498-1543 Holbein +-+-+-+-+

53. But why should four unfortunate masters be dropped out?

Well, I want to drop them out, at any rate; but not in disrespect. In hope, on the contrary, to make you remember them very separately indeed;–for this following reason.

We are in the careless habit of speaking of men who form a great number of pupils, and have a host of inferior satellites round them, as masters of great schools.

But before you call a man a master, you should ask, Are his pupils greater or less than himself? If they are greater than himself, he is a master indeed;–he has been a true teacher. But if all his pupils are less than himself, he may have been a great man, but in all probability has been a bad master, or no master.

Now these men, whom I have signally left out of my groups, are true Masters.

Niccola Pisano taught all Italy; but chiefly his own son, who succeeded, and in some things very much surpassed him.

Orcagna taught all Italy, after him, down to Michael Angelo. And these two–Lippi, the religious schools, Verrocchio, the artist schools, of their century.

Lippi taught Sandro Botticelli; and Verrocchio taught Lionardo da Vinci, Lorenzo di Credi, and Perugino. Have I not good reason to separate the masters of such pupils from the schools they created?

54. But how is it that I can drop just the cards I want out of my pack?

Well, certainly I force and fit matters a little: I leave some men out of my list whom I should like to have in it;–Benozzo Gozzoli, for instance, and Mino da Fiesole; but I can do without them, and so can you also, for the present. I catch Luca by a hair’s-breadth only, with my 1400 rod; but on the whole, with very little coaxing, I get the groups in this memorable and quite literally ‘handy’ form. For see, I write my lists of five, five, and seven, on bits of pasteboard; I hinge my rods to these; and you can brandish the school of 1400 in your left hand, and of 1500 in your right, like–railway signals;–and I wish all railway signals were as clear. Once learn, thoroughly, the groups in this artificially contracted form, and you can refine and complete afterwards at your leisure.

55. And thus actually flourishing my two pennons, and getting my grip of the men, in either hand, I find a notable thing concerning my two flags. The men whose names I hold in my left hand are all sculptors; the men whose names I hold in my right are all painters.

You will infallibly suspect me of having chosen them thus on purpose. No, honor bright!–I chose simply the greatest men,–those I wanted to talk to you about. I arranged them by their dates; I put them into three conclusive pennons; and behold what follows!

56. Farther, note this: in the 1300 group, four out of the five men are architects as well as sculptors and painters. In the 1400 group, there is one architect; in the 1500, none. And the meaning of that is, that in 1300 the arts were all united, and duly led by architecture; in 1400, sculpture began to assume too separate a power to herself; in 1500, painting arrogated all, and, at last, betrayed all. From which, with much other collateral evidence, you may justly conclude that the three arts ought to be practiced together, and that they naturally are so. I long since asserted that no man could be an architect who was not a sculptor. As I learned more and more of my business, I perceived also that no man could be a sculptor who was not an architect;–that is to say, who had not knowledge enough, and pleasure enough in structural law, to be able to build, on occasion, better than a mere builder. And so, finally, I now positively aver to you that nobody, in the graphic arts, can be quite rightly a master of anything, who is not master of everything!

57. The junction of the three arts in men’s minds, at the best times, is shortly signified in these words of Chaucer. Love’s Garden,

Everidele

Enclosed was, and walled well

With high walls, embatailled,

Portrayed without, and well entayled

With many rich portraitures.

The French original is better still, and gives four arts in unison:–

Quant suis avant un pou alé

Et vy un vergier grant et le,

Bien cloz de bon mur batillié

Pourtrait dehors, et entaillié

Ou (for au) maintes riches escriptures.

Read also carefully the description of the temples of Mars and Venus in the Knight’s Tale. Contemporary French uses ‘entaille’ even of solid sculpture and of the living form; and Pygmalion, as a perfect master, professes wood carving, ivory carving, waxwork, and iron-work, no less than stone sculpture:–

Pimalion, uns entaillieres

Pourtraians en fuz[K] et en pierres,

En mettaux, en os, et en cire,

Et en toute autre matire.

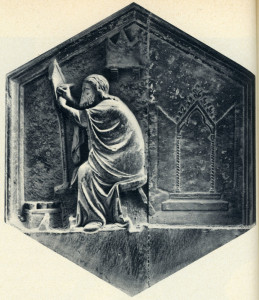

58. I made a little sketch, when last in Florence, of a subject which will fix the idea of this unity of the arts in your minds. At the base of the tower of Giotto are two rows of hexagonal panels, filled with bas-reliefs. Some of these are by unknown hands,–some by Andrea Pisano, some by Luca della Robbia, two by Giotto himself; of these I sketched the panel representing the art of Painting.

58. I made a little sketch, when last in Florence, of a subject which will fix the idea of this unity of the arts in your minds. At the base of the tower of Giotto are two rows of hexagonal panels, filled with bas-reliefs. Some of these are by unknown hands,–some by Andrea Pisano, some by Luca della Robbia, two by Giotto himself; of these I sketched the panel representing the art of Painting.

You have in that bas-relief one of the foundation-stones of the most perfectly built tower in Europe; you have that stone carved by its architect’s own hand; you find, further, that this architect and sculptor was the greatest painter of his time, and the friend of the greatest poet; and you have represented by him a painter in his shop,–bottega,–as symbolic of the entire art of painting.

You have in that bas-relief one of the foundation-stones of the most perfectly built tower in Europe; you have that stone carved by its architect’s own hand; you find, further, that this architect and sculptor was the greatest painter of his time, and the friend of the greatest poet; and you have represented by him a painter in his shop,–bottega,–as symbolic of the entire art of painting.

59. In which representation, please note how carefully Giotto shows you the tabernacles or niches, in which the paintings are to be placed. Not independent of their frames, these panels of his, you see!

Have you ever considered, in the early history of painting, how important also is the history of the frame maker? It is a matter, I assure you, needing your very best consideration. For the frame was made before the picture. The painted window is much, but the aperture it fills was thought of before it. The fresco by Giotto is much, but the vault it adorns was planned first. Who thought of these;–who built?

Questions taking us far back before the birth of the shepherd boy of Fésole–questions not to be answered by history of painting only, still less of painting in Italy only.

60. And in pointing out to you this fact, I may once for all prove to you the essential unity of the arts, and show you how impossible it is to understand one without reference to another. Which I wish you to observe all the more closely, that you may use, without danger of being misled, the data, of unequaled value, which have been collected by Crowe and Cavalcaselle, in the book which they have called a History of Painting in Italy, but which is in fact only a dictionary of details relating to that history. Such a title is an absurdity on the face of it. For, first, you can no more write the history of painting in Italy than you can write the history of the south wind in Italy. The sirocco does indeed produce certain effects at Genoa, and others at Rome; but what would be the value of a treatise upon the winds, which, for the honor of any country, assumed that every city of it had a native sirocco?

But, further,–imagine what success would attend the meteorologist who should set himself to give an account of the south wind, but take no notice of the north!

And, finally, suppose an attempt to give you an account of either wind, but none of the seas, or mountain passes, by which they were nourished, or directed.

61. For instance, I am in this course of lectures to give you an account of a single and minor branch of graphic art,–engraving. But observe how many references to local circumstances it involves. There are three materials for it, we said;–stone, wood, and metal. Stone engraving is the art of countries possessing marble and gems; wood engraving, of countries overgrown with forest; metal engraving, of countries possessing treasures of silver and gold. And the style of a stone engraver is formed on pillars and pyramids; the style of a wood engraver under the eaves of larch cottages; the style of a metal engraver in the treasuries of kings. Do you suppose I could rightly explain to you the value of a single touch on brass by Finiguerra, or on box by Bewick, unless I had grasp of the great laws of climate and country; and could trace the inherited sirocco or tramontana of thought to which the souls and bodies of the men owed their existence?

62. You see that in this flag of 1300 there is a dark strong line in the center, against which you read the name of Arnolfo.

In writing our Florentine Dunciad, or History of Fools, can we possibly begin with a better day than All Fools’ Day? On All Fools’ Day—the first, if you like better so to call it, of the month of opening,—in the year 1300, is signed the document making Arnolfo a citizen of Florence, and in 1310 he dies, chief master of the works of the cathedral there. To this man, Crowe and Cavalcaselle give half a page, out of three volumes of five hundred pages each.

But lower down in my flag, (not put there because of any inferiority, but by order of chronology,) you will see a name sufficiently familiar to you–that of Giotto; and to him, our historians of painting in Italy give some hundred pages, under the impression, stated by them at page 243 of their volume, that “in his hands, art in the Peninsula became entitled for the first time to the name of Italian.”

63. Art became Italian! Yes, but what art? Your authors give a perspective–or what they call such,–of the upper church of Assisi, as if that were merely an accidental occurrence of blind walls for Giotto to paint on!

But how came the upper church of Assisi there? How came it to be vaulted–to be aisled? How came Giotto to be asked to paint upon it?

The art that built it, good or bad, must have been an Italian one, before Giotto. He could not have painted on the air. Let us see how his panels were made for him.

64. This Captain–the center of our first group–Arnolfo, has always hitherto been called ‘Arnolfo di Lapo;’–Arnolfo the son of Lapo.

Modern investigators come down on us delightedly, to tell us–Arnolfo was not the son of Lapo.

In these days you will have half a dozen doctors, writing each a long book, and the sense of all will be,–Arnolfo wasn’t the son of Lapo. Much good may you get of that!

Well, you will find the fact to be, there was a great Northman builder, a true son of Thor, who came down into Italy in 1200, served the order of St. Francis there, built Assisi, taught Arnolfo how to build, with Thor’s hammer, and disappeared, leaving his name uncertain—Jacopo–Lapo–nobody knows what. Arnolfo always recognizes this man as his true father, who put the soul-life into him; he is known to his Florentines always as Lapo’s Arnolfo.

That, or some likeness of that, is the vital fact. You never can get at the literal limitation of living facts. They disguise themselves by the very strength of their life: get told again and again in different ways by all manner of people;–the literalness of them is turned topsy-turvy, inside-out, over and over again;–then the fools come and read them wrong side upwards, or else, say there never was a fact at all. Nothing delights a true blockhead so much as to prove a negative;–to show that everybody has been wrong. Fancy the delicious sensation, to an empty-headed creature, of fancying for a moment that he has emptied everybody else’s head as well as his own! nay, that, for once, his own hollow bottle of a head has had the best of other bottles, and has been first empty;–first to know–nothing.

65. Hold, then, steadily the first tradition about this Arnolfo. That his real father was called “Cambio” matters to you not a straw. That he never called himself Cambio’s Arnolfo–that nobody else ever called him so, down to Vasari’s time, is an infinitely significant fact to you. In my twenty-second letter in Fors Clavigera you will find some account of the noble habit of the Italian artists to call themselves by their masters’ names, considering their master as their true father. If not the name of the master, they take that of their native place, as having owed the character of their life to that. They rarely take their own family name: sometimes it is not even known,–when best known, it is unfamiliar to us. The great Pisan artists, for instance, never bear any other name than ‘the Pisan;’ among the other five-and-twenty names in my list, not above six, I think, the two German, with four Italian, are family names. Perugino, (Peter of Perugia,) Luini, (Bernard of Luino,) Quercia, (James of Quercia,) Correggio, (Anthony of Correggio,) are named from their native places. Nobody would have understood me if I had called Giotto, ‘Ambrose Bondone;’ or Tintoret, Robusti; or even Raphael, Sanzio. Botticelli is named from his master; Ghiberti from his father-in-law; and Ghirlandajo from his work. Orcagna, who did, for a wonder, name himself from his father, Andrea Cione, of Florence, has been always called ‘Angel’ by everybody else; while Arnolfo, who never named himself from his father, is now like to be fathered against his will.

But, I again beg of you, keep to the old story. For it represents, however inaccurately in detail, clearly in sum, the fact, that some great master of German Gothic at this time came down into Italy, and changed the entire form of Italian architecture by his touch. So that while Niccola and Giovanni Pisano are still virtually Greek artists, experimentally introducing Gothic forms, Arnolfo and Giotto adopt the entire Gothic ideal of form, and thenceforward use the pointed arch and steep gable as the limits of sculpture.

66. Hitherto I have been speaking of the relations of my twenty-five men to each other. But now, please note their relations altogether to the art before them. These twenty-five include, I say, all the great masters of Christian art.

Before them, the art was too savage to be Christian; afterwards, too carnal to be Christian.

Too savage to be Christian? I will justify that assertion hereafter; but you will find that the European art of 1200 includes all the most developed and characteristic conditions of the style in the north which you have probably been accustomed to think of as NORMAN, and which you may always most conveniently call so; and the most developed conditions of the style in the south, which, formed out of effete Greek, Persian, and Roman tradition, you may, in like manner, most conveniently express by the familiar word BYZANTINE. Whatever you call them, they are in origin adverse in temper, and remain so up to the year 1200. Then an influence appears, seemingly that of one man, Nicholas the Pisan, (our first MASTER, observe,) and a new spirit adopts what is best in each, and gives to what it adopts a new energy of its own; namely, this conscientious and didactic power which is the speciality of its progressive existence. And just as the new-born and natural art of Athens collects and reanimates Pelasgian and Egyptian tradition, purifying their worship, and perfecting their work, into the living heathen faith of the world, so this new-born and natural art of Florence collects and animates the Norman and Byzantine tradition, and forms out of the perfected worship and work of both, the honest Christian faith, and vital craftsmanship, of the world.

67. Get this first summary, therefore, well into your minds. The word’Norman’ I use roughly for North-savage;–roughly, but advisedly. I mean Lombard, Scandinavian, Frankish; everything north-savage that you can think of, except Saxon. (I have a reason for that exception; never mind it just now.)[L]

All north-savage I call NORMAN, all south-savage I call BYZANTINE; this latter including dead native Greek primarily–then dead foreign Greek, in Rome;–then Arabian–Persian–Phoenician–Indian–all you can think of, in art of hot countries, up to this year 1200, I rank under the one term Byzantine. Now all this cold art–Norman, and all this hot art–Byzantine, is virtually dead, till 1200. It has no conscience, no didactic power;[M] it is devoid of both, in the sense that dreams are.

Then in the thirteenth century, men wake as if they heard an alarum through the whole vault of heaven, and true human life begins again, and the cradle of this life is the Val d’Arno. There the northern and southern nations meet; there they lay down their enmities; there they are first baptized unto John’s baptism for the remission of sins; there is born, and thence exiled,–thought faithless, for breaking the font of baptism to save a child from drowning, in his ‘bel San Giovanni,’–the greatest of Christian poets; he who had pity even for the lost.

68. Now, therefore, my whole history of Christian architecture and painting begins with this Baptistery of Florence, and with its associated Cathedral. Arnolfo brought the one into the form in which you now see it; he laid the foundation of the other, and that to purpose, and he is therefore the CAPTAIN of our first school.

For this Florentine Baptistery[N] is the great one of the world. Here is the center of Christian knowledge and power.

And it is one piece of large engraving. White substance, cut into, and filled with black, and dark-green.

No more perfect work was afterwards done; and I wish you to grasp the idea of this building clearly and irrevocably,–first, in order (as I told you in a previous lecture) to quit yourselves thoroughly of the idea that ornament should be decorated construction; and, secondly, as the noblest type of the intaglio ornamentation, which developed itself into all minor application of black and white to engraving.

69. That it should do so first at Florence, was the natural sequence, and the just reward, of the ancient skill of Etruria in chased metal-work. The effects produced in gold, either by embossing or engraving, were the direct means of giving interest to his surfaces at the command of the ‘auri faber,’ or orfevre: and every conceivable artifice of studding, chiseling, and interlacing was exhausted by the artists in gold, who were at the head of the metal-workers, and from whom the ranks of the sculptors were reinforced.

The old French word ‘orfroiz,’ (aurifrigia,) expresses essentially what we call ‘frosted’ work in gold; that which resembles small dew or crystals of hoar-frost; the ‘frigia’ coming from the Latin frigus. To chase, or enchase, is not properly said of the gold; but of the jewel which it secures with hoops or ridges, (French, enchasser[O]). Then the armorer, or cup and casket maker, added to this kind of decoration that of flat inlaid enamel; and the silver-worker, finding that the raised filigree (still a staple at Genoa) only attracted tarnish, or got crushed, early sought to decorate a surface which would bear external friction, with labyrinths of safe incision.

70. Of the security of incision as a means of permanent decoration, as opposed to ordinary carving, here is a beautiful instance in the base of one of the external shafts of the Cathedral of Lucca; thirteenth-century work, which by this time, had it been carved in relief, would have been a shapeless remnant of indecipherable bosses. But it is still as safe as if it had been cut yesterday, because the smooth round mass of the pillar is entirely undisturbed; into that, furrows are cut with a chisel as much under command and as powerful as a burin. The effect of the design is trusted entirely to the depth of these incisions–here dying out and expiring in the light of the marble, there deepened, by drill holes, into as definitely a black line as if it were drawn with ink; and describing the outline of the leafage with a delicacy of touch and of perception which no man will ever surpass, and which very few have rivaled, in the proudest days of design.

71. This security, in silver plates, was completed by filling the furrows with the black paste which at once exhibited and preserved them. The transition from that niello-work to modern engraving is one of no real moment: my object is to make you understand the qualities which constitute the merit of the engraving, whether charged with niello or ink. And this I hope ultimately to accomplish by studying with you some of the works of the four men, Botticelli and Mantegna in the south, Dürer and Holbein in the north, whose names I have put in our last flag, above and beneath those of the three mighty painters, Perugino the captain, Bellini on one side–Luini on the other.

The four following lectures[P] will contain data necessary for such study: you must wait longer before I can place before you those by which I can justify what must greatly surprise some of my audience–my having given Perugino the captain’s place among the three painters.

72. But I do so, at least primarily, because what is commonly thought affected in his design is indeed the true remains of the great architectural symmetry which was soon to be lost, and which makes him the true follower of Arnolfo and Brunelleschi; and because he is a sound craftsman and workman to the very heart’s core. A noble, gracious, and quiet laborer from youth to death,–never weary, never impatient, never untender, never untrue. Not Tintoret in power, not Raphael in flexibility, not Holbein in veracity, not Luini in love,–their gathered gifts he has, in balanced and fruitful measure, fit to be the guide, and impulse, and father of all.

FOOTNOTES:

[D] Compare “Aratra Pentelici,” § 154.

[E] “Holbein and His Time,” 4to, Bentley, 1872, (a very valuable book,) p. 17. Italics mine.

[F] See Carlyle, “Frederick,” Book III., chap. viii.

[G] I believe I am taking too much trouble in writing these lectures. This sentence, § 44, has cost me, I suppose, first and last, about as many hours as there are lines in it;–and my choice of these two words, faith and death, as representatives of power, will perhaps, after all, only puzzle the reader.

[H] He is said by Vasari to have called Francia the like. Francia is a child compared to Perugino; but a finished working-goldsmith and ornamental painter nevertheless; and one of the very last men to be called ‘goffo,’ except by unparalleled insolence.

[I] The diagram used at the lecture is engraved on page 30; the reader had better draw it larger for himself, as it had to be made inconveniently small for this size of leaf.

[J] ‘Ascertained,’ scarcely any date ever is, quite satisfactorily. The diagram only represents what is practically and broadly true. I may have to modify it greatly in detail.

[K] For fust, log of wood, erroneously ‘fer’ in the later printed editions. Compare the account of the works of Art and Nature, towards the end of the Romance of the Rose.

[L] Of course it would have been impossible to express in any accurate terms, short enough for the compass of a lecture, the conditions of opposition between the Heptarchy and the Northmen;–between the Byzantine and Roman;–and between the Byzantine and Arab, which form minor, but not less trenchant, divisions of Art-province, for subsequent delineation. If you can refer to my “Stones of Venice,” see § 20 of its first chapter.

[M] Again much too broad a statement: not to be qualified but by a length of explanation here impossible. My lectures on Architecture, now in preparation (“Val d’Arno”), will contain further detail.

[N] At the side of my page, here, I find the following memorandum, which was expanded in the viva-voce lecture. The reader must make what he can of it, for I can’t expand it here.

Sense of Italian Church plan.

Baptistery, to make Christians in; house, or dome, for them to pray and be preached to in; bell-tower, to ring all over the town, when they were either to pray together, rejoice together, or to be warned of danger.

Harvey’s picture of the Covenanters, with a shepherd on the outlook, as a campanile.

[O] And ‘chassis,’ a window frame, or tracery.

[P] This present lecture does not, as at present published, justify its title; because I have not thought it necessary to write the viva-voce portions of it which amplified the 69th paragraph. I will give the substance of them in better form elsewhere; meantime the part of the lecture here given may be in its own way useful.